You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome in the Athlete: Part 1

Chris Mallac explores the different causes of thoracic outlet syndrome and the typical signs and symptoms that usually plague an athlete in this confusing, poorly defined, and difficult-to-diagnose problem.

First described over 200 years ago and named as Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) in 1956, TOS is a pathological disease process that involves a compression of the neurovascular bundle of the brachial plexus and possibly the associated veins and arteries(1,2). This compression results in a constellation of symptoms that may mimic other more common cervical and upper limb pathologies.

The anatomical thoracic outlet ‘container’ comprises numerous structures that may create neurovascular compression. The term TOS describes a symptom complex defined by the anatomical location of the pathophysiology and is not a true diagnosis.

Overall, it is more common in women (4:1) and estimated to affect up to 8% of the population(3,4). However, the incidence in athletes is unclear. In athletes, it is most common in baseball pitchers(5), golfers, weight lifters, volleyballers, swimmers, rowers, water polo players, gymnasts, tennis players, and those in throwing sports like cricket(6,7,8).

Pathophysiology

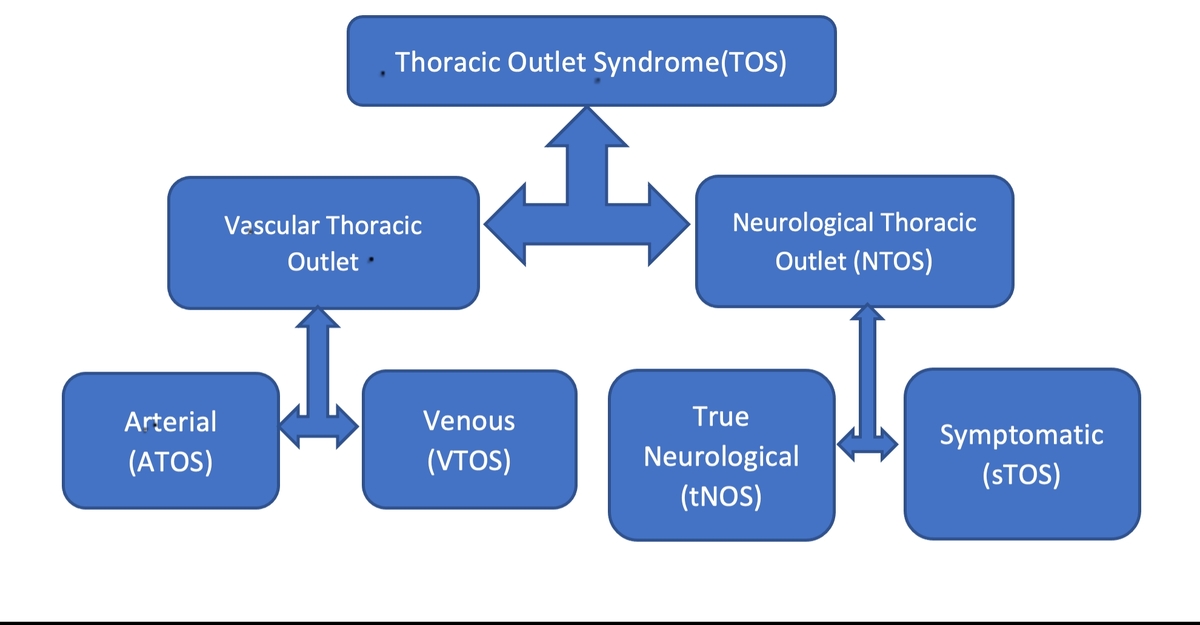

There are two types of TOS– neurological TOS (NTOS) and vascular TOS (see figure 1) (9-16):

- Neurological TOS (NTOS): This is the most common type, and neurological symptoms appear in 90-97% of patients with TOS(17-19). This is further subdivided(13,14):

- True NTOS

- Symptomatic NTOS

- Vascular TOS is subdivided into:

- VTOS: Venous compression of the subclavian vein (3-5%)(19)

- ATOS: Arterial compression of the subclavian artery (1%)(19)

Vascular TOS is easier to diagnose because it has actual vascular signs and symptoms caused by an anatomical fault, such as a cervical rib or large first rib. However, it is not as common as the harder-to-diagnose symptomatic TOS(3). Adding to the complexity, both NTOS and vascular TOS co-exist in five to 10% of TOS patients(11).

Relevant anatomy and pathophysiology

- Interscalene triangle compression/traction zone

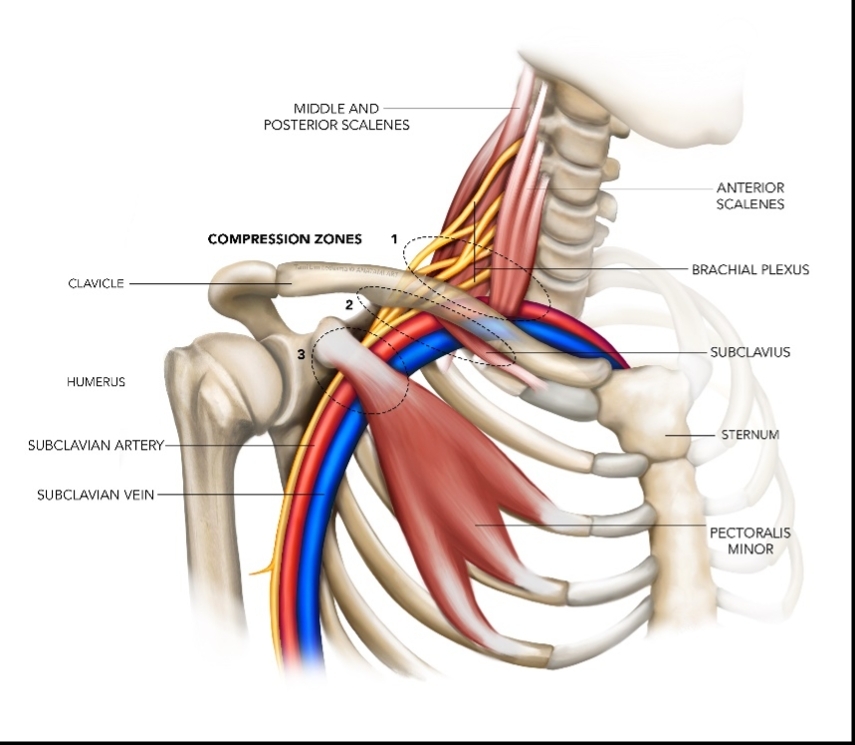

Thoracic outlet syndrome may occur at three possible anatomical sites (see figure 2).

Related Files

The brachial plexus (formed by the C5 to T1 nerves) and the subclavian artery exit the neck area between the anterior and middle scalene and the medial surface of the first rib. This area is the first possible site of entrapment. Of note, the subclavian vein does not pass between these two scalene muscles as it passes anterior and inferior to the anterior scalene before joining the internal jugular vein. Therefore, the interscalene triangle cannot be a source of compression or traction for the venous TOS varieties(9-11).

Possible reasons for entrapment at the interscalene triangle;

- Hypertrophy of the anterior scalene (noted in weightlifters).

- Brachial plexus passing through the anterior scalene.

- A broad insertion of the anterior scalene onto the first rib, with possible overlapping of a wide tendon insertion with the adjacent scalene muscle

- Presence of a cervical rib.

- Fibrous bands in and around the first rib

A cervical rib is an extra rib that originates from the seventh cervical vertebrae. It is present in only 1% of the general population and only 10% of these experience any symptoms(22). These may be complete and wrap around to join the sternum, or they may incomplete and have associated fibrous bands that bind them to the first rib.

Other causes include spasms of the scalene muscles caused by injury to the cervical spine or by overuse due to excessive traction forces (such as carrying heavy loaded objects, for example, deadlifting) and excessive use as a compensatory elevator of the shoulder due to upper trapezius weakness.

A Greek study found that compression of the brachial plexus or subclavian artery in athletes was primarily due to scalene muscle hypertrophy(23). The scalene muscles in wrestlers, handballers, swimmers, and rowers can hypertrophy, possibly making them more prone to exercise-induced compression, particularly in overhead positions.

- Costoclavicular compression/traction zone

The brachial plexus, subclavian artery, and subclavian vein continue over the first rib with the clavicle sitting atop them. This costoclavicular space, bordered by the first rib posteromedially, anteriorly by the middle third of the clavicle, and posterolaterally by the upper border of the scapula, is the site of the second possible and most common compression zone(24, 25).

Possible reasons for entrapment at the costoclavicular space include:

- Depressed clavicle posture.

- Overdeveloped first rib.

- Elevated first rib.

- Clavicular deformity following trauma or fracture.

- Presence of anatomical anomalies such as a subclavius posticus muscle (exclusive to athletes)

- Retropectoral compression/traction zone

Traveling from the costoclavicular space, the neurovascular bundle approaches the third site of compression. The area is posterior to the pectoralis minor tendon’s insertion on the coracoid process. This entrapment site, known as the thoraco-coraco pectoral space or the retropectoralis space, is bordered by the second to fourth ribs posteriorly, the pectoralis minor anteriorly, and the coracoid process superiorly(20, 27).

The primary cause of entrapment here is hypertrophy of the pectoralis minor muscle. Some suggest that this type of compression is more appropriately termed ‘neurogenic pectoralis minor syndrome.’ Thus, reserving the term NTOS for those suffering compression at the interscalene triangle(11).

Signs and symptoms

Diagnosis of TOS is a clinical diagnosis. The detailed history of the presenting pathology and the descriptive signs and symptoms are the best clinical indicators for TOS. Objective tests are particularly unhelpful as isolated tests. Instead, a collection of positive tests with a symptom cluster is the most accurate diagnostic criteria for TOS(13,14, 28, 29).

- Vascular TOS

- Arterial TOS

This subclavian artery compression produces stenosis, post stenotic dilatation, intimal injury, aneurysm formation, and mural thrombosis. It is more common in younger adults with a history of heavy arm use. It may be caused by hypertrophy of the scalene muscles or fascial bands in and around them from overuse in athletes. In 85% of cases, a cervical rib, a large C7 transverse process, or a callus formation on an old clavicular fracture causes the compression(30, 31).

However, a differential diagnosis that produces similar signs and symptoms as arterial TOS is axillary artery compression. This type of compression occurs under the pectoralis minor tendon when the arm is in positions of abduction and external rotation. It results in similar arterial compression symptoms as subclavian compression in the interscalene triangle(5,32).

Typical features include(9-16, 25):

Subjective

-

- Pain in hand is common, not in shoulder and neck

- Claudication

- Feeling of stiffness/heaviness/ fatigability

- Cramp in hand or upper limb

- Paresthesia due to ischemia

Objective

-

- Raynaud’s Phenomenon

- Upper limb and hand ischemia;

- Multiple upper limb arterial emobilization

- Vasomotor changes

- Digital gangrene

- Absent/decreased arterial pulse

- Swelling

- Blood pressure differential >20mmHg

It may be confirmed on duplex ultrasound and angiography in a seated position or, by contrast-enhanced angiography in known compression positions (6, 33). Catheter-based angiography, although invasive, is the gold standard investigation for ATOS(30).

- Venous TOS

The subclavian vein is compressed and may cause unilateral arm swelling without lymphatic obstruction. It is more common in younger men and may be preceded by heavy use of the arm, particularly in abduction and external rotation positions. The symptoms may present immediately or within 24 hours of the exposure(11, 12).

Venous TOS is more common than arterial TOS due to the subclavian vein’s course moving upwards and ‘slinging’ over the first rib before it descends downwards through the retropectoral space. A thickened costoclavicular ligament may also cause stenosis of the vein at the first rib level.

Furthermore, compression of the subclavian vein between the clavicle, first rib, and subclavius tendon causes effort thrombosis in a condition known as Paget-Schroetter Syndrome. Although rare, it has been described in young athletes(34). McCleery Syndrome is the term for intermittent positional obstruction in the absence of thrombosis(11).

Typical features of VTOS include(9-16, 25):

Subjective

-

- Asymmetrical upper limb edema with possible cyanosis (reddish-blue).

- Pain and fatigability in the affected arm with use.

- Stiffness/heaviness

- Paresthesia is secondary to edema

Objective

-

- Venous engorgement

- Axillary or subclavian vein thrombosis and palpable clotted veins in the neck, upper am, and anterior chest

- Visible cyanosis

Tests used to confirm VTOS include venous ultrasound studies, venous scintillation scans and catheter-based venography(16). Duplex ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 78%-100% and specificity of 82-100%. It is a fast and non-invasive investigation but does have a false negative rate of up to 30%(35).

- Neurological TOS

- True neurological

True NTOS is rare. It is caused by irritation, compression, or traction of the brachial plexus from a bony or soft tissue abnormality present congenitally, such as partial cervical rib or fibrous bands. Repetitive or significant trauma, such as a whiplash-type injury, postural, or occupational factors may also contribute to neurological symptoms. It is more common in middle-aged females(24).

True NTOS is broken down further into Lower Plexus Syndrome and Upper Plexus Syndrome(13). Neurodiagnostic testing such as an EMG or nerve conduction study helps confirm these subdivisions.

Lower plexus syndrome (C7/8/T1 pattern)

Lower plexus syndrome is the most common pattern and occurs in about 80% of NTOS sufferers. The T1 fibers are the most commonly affected(24, 26).

Symptoms of lower plexus syndrome include:

-

- Sensory changes in the fourth and fifth fingers.

- Sensory loss above the medial elbow.

- Pain and paresthesia over the medial aspect of the arm, forearm, ulnar digits.

- Hand weakness, loss of dexterity, wasting of lateral thenar muscles and hypothenar muscles.

Upper plexus syndrome (C5/6/7 pattern)

Symptoms of upper plexus syndrome are:

-

- Sensory changes in the first three fingers, and may also have numbness in the cheek, earlobe, back of the shoulder, or lateral arm.

- Weakness in deltoid, biceps, triceps, scapular muscles, and forearm extensors.

- Pain in the anterior neck, chest, supraclavicular region, triceps, deltoids, periscapular muscles, outer arm to forearm extensors, and pain in the pectoral region (pseudo angina), face, mandible, temple, ear with occipital headaches.

- May have dizziness, vertigo, and blurred vision.

-

- Symptomatic Neurological

By far the most common variety of TOS. It is an anatomical term that describes the pain region rather than the actual underlying cause. Causes are usually multifactorial. Typically, there’s no bony or soft tissue anomaly. Intermittent compression of the neurovascular bundle is due to repetitive postural, occupational, or sporting factors that create transient narrowing in the cervical or thoracic outlet. This variant is sometimes called ‘disputed’ and ‘non-specific’ TOS(37).

Typical features include(9-16, 25):

-

- Distal symptoms ranging from spasm, pain, deep ache, tingling, numbness, and tightness in the forearm, hands, and wrists with heavy use.

- Feelings of tiredness and weakness in the hand or upper limb, especially with overhead sporting activities.

- Feelings of tenderness, swelling, or loss of motor control.

- Possible pain in lower neck, shoulders, elbow, upper back, headaches.

- Pain aggravated by overhead activities or activities that depress the scapula.

- Pain at rest and night pain

- Neurological symptoms, if present, are transient and intermittent.

- Paresthesia in digits, typically upon wakening.

Symptomatic TOS is a clinical diagnosis, and no investigative tests are useful for this condition. Due to the confusing and perplexing nature of symptomatic TOS and the extensive overlap it has with other upper limb pathologies and cervical radiculopathies, researchers continue to narrow the diagnostic criteria for this subset of TOS patients. Namely,

-

- Balderman et al. (2017)(15) have summarized the criteria agreed upon by the Consortium for Research and Education on Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (CORE_TOS) for diagnosis of neurogenic TOS.

- Illig et al. (2016)(11) provide the Society for Vascular Surgery’s framework that identifies that the diagnosis of TOS is made on positive findings in three from four key criteria.

Differential Diagnosis

The presenting signs and symptoms may initially be vague and difficult to differentiate from other possible shoulder and cervical pathologies in the overhead athlete. Often the definitive diagnosis is made through a process of eliminating other possible differential diagnoses(31). A myriad of other pathologies produce similar signs and symptoms to TOS such as pain in the shoulder and neck, pain, or neurological signs that extend to the medial side of the arm.

Possible differential diagnosis include(9-14):

- Cervical nerve root impingement (radiculopathy)

- Peripheral neuropathies.

- Glenohumeral instability

- Brachial neuritis

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Cubital tunnel syndrome

- De Quervains syndrome

- Lateral epicondylitis and posterior interosseus nerve entrapment

- Humeral hypertrophy

- Pectoralis minor hypertrophy

- Quadrilateral Space Syndrome

- Vascular occlusive disease

- Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

- Horner’s Syndrome

- Raynaud’s disease

- Sinister pathologies such as Pancoast Tumor.

- Angina

Conclusion

Thoracic outlet syndrome is a complex and confusing anatomical pathology that may mimic many other forms of cervical and shoulder pathologies in the athlete. The variant NTOS is the more common variety with vascular TOS diagnosed in five percent of cases. Part two of this series will discuss the clinical tests used by clinicians to diagnose TOS and intervention strategies, both surgical and conservative, the clinician needs to consider in managing the athlete involved in overhead sports.

References

- Orthop Clin North Am. 1975,6(2):507-19

- Prc Mayo Clin. 1956, 31:281–7

- World J Surg 2003;27:545-50.

- J Pain Relief. 2015. 4(2). 1-7

- J of Vasc Surgery 2011, 53(5); 1329-1340.

- J of Vasc Surgery. 2017, 66(6), 1798-1805.

- J of Vasc Surgery. 2014, 60(4), 1012-1018.

- Manske R.C. in Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. A Team Approach 4th Giangarra et al

- 2018, 8, 21; doi:10.3390.

- Pain Therapy. 2019, 8: 5-18.

- Journal of Vasc Surgery. 2016, 64(3). e23-e35.

- Muscle Nerve. 2017; 56(4); 663-73

- Int J of Osteopathic Medicine 13 (2010) 133-142

- Manual Therapy 15 (2010) 305-314

- J Vasc Surg. 2017;66(2):533–44

- Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2020, 13:457–471

- Scientifica 2014;

- Am J Sports Med 2002; 30: 708-712.

- J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: pp. 601-604.

- 2006;26:1735–50.

- Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;8:183–9.

- Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:131–46.

- The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008, 36(2); 369-374

- 2005;17(2):5-9

- Cochrane Database Syst Rev2014 Nov 26;(11):CD007218.

- Clin J Sport Med 2017;27:e29–e31)

- 2016; 36(4): 984-1000

- Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 2010. 18:2, 74-83

- Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 2010. 18:3, 132-138

- Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016. 28; 151-157

- Current Opinion in Cardiology. 2010; 25: 535-540.

- Radiol Clin. 1978; 47. 423-7

- J Vasc Surgery. 1990. 11: 761-9.

- J Vasc Surgery. 2008; 47: 809-20.

- Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2014, 13(2); 81-85.

- Stewman Curr Sports Med Rep 2014; 13(2); 100-106.

- Wilbourn AJ. Thoracic outlet syndrome. In: Syllabus, Course D: Controversies in entrapment neuropathies. Rochester, MN: American Association of Electromyography and Electrodiagnosis; 1984. p 28–38.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.