You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Unlocking the Mystery: Double Crush Syndrome

Samantha Nupen explores this syndrome’s pathology and effective physiotherapy management.

Double crush syndrome mechanism

The first description of double crush syndrome was in 1973(1). There are typically central and peripheral areas of symptoms (see table 1). The hypothesis is that there is a disruption of axoplasmic flow or neural elasticity that causes nerves that have been compromised at one site to become more susceptible to compromise at another location.

Table 1: Common areas implicated in double crush syndrome in the upper and lower limb(2)

| Central Area | Peripheral Area |

| Cervical nerve root compression | Median nerve at the wrist (i.e., carpal tunnel syndrome) |

| Thoracic outlet syndrome | Carpal tunnel syndrome |

| Pronator teres syndrome | Carpal tunnel syndrome |

| Cervical nerve root compression | Ulnar nerve at the elbow (i.e., cubital tunnel syndrome) |

| Thoracic outlet syndrome | Cubital tunnel syndrome |

Cubital tunnel syndrome |

Ulnar nerve at the wrist (i.e., Guyon’s tunnel syndrome) |

| Cervical nerve root | Radial nerve at elbow (i.e., radial tunnel syndrome) |

| L5 nerve root compression | Common peroneal nerve at the knee |

Repetitive strain or overuse is often a contributing factor, but sometimes trauma precedes a double crush syndrome presentation. For example, in the lower limb, hip dislocation and acetabular fracture with sciatic nerve involvement may present later with peroneal nerve involvement.

Mechanical compression of a nerve in one area adversely affects neural mobility in another area. For example, anatomical anomalies that cause mechanical compression, like a cervical rib, are sometimes present. Or spondylosis of the spine with osteophytes encroaching on the nerve root could cause mechanical compression. Likewise, scarring from an old injury like a hamstring strain could cause tethering of the sciatic nerve, compromising its mobility. Or an old fracture of the neck fibula with a bony callus could mechanically compromise the common peroneal nerve. All of these will affect the mobility or neurodynamics of the nerve either proximally or distally to the mechanical compression.

RED FLAG WARNING

It is critical to exclude systemic diseases such as multiple sclerosis, diabetes, thyroid disease, and chemotherapeutic agents that could be causing nerve damage.

The key is to identify all of the areas of compromise along the path of the nerve during the assessment, and treatment aims to improve the mobility of the nerve in each area. There are two systems in the body that stretch from the head to the toes: the myofascial and neural systems.

The myofascial system

Myofascia surrounds all our bodies’ muscles, tendons, ligaments, organs, nerves, joints, and bones. Healthy myofascia is flexible and stretches as the body moves. A mobile and flexible myofascial system allows other structures to move freely. This includes the neural system. When myofascia tightens up, it restricts movement and can cause pain. Releasing and ensuring a fully mobile myofascial system will improve neural mobility and help alleviate pain.

The neural system

The neural system conductance is tested clinically with a neurological examination that includes muscle power, sensation, and reflex testing. These clinical tests, as well as nerve conductance studies, are generally normal in double crush syndromes. A clear neural examination in the instance of a central area of symptoms with a peripheral area of symptoms strengthens the hypothesis of a double crush syndrome. Neural mobility testing provides essential information in double crush syndrome; the same tests become a valuable part of treatment(3-6).

Table 2: The difference between a neurological and neurodynamic examination.

Neurological examination |

Neurodynamic examination |

| Tests conductance of the nerve root | Tests mobility of the nerve |

| Symptoms dermatomal | Symptoms non-dermatomal |

|

Upper limb tension tests

Lower limb tension tests

|

Table 3: Areas where nerves are least mobile and are often implicated in double crush syndrome(7).

| Main tension points in the spine |

|

| Neural branches |

|

| Nerve near soft tissue or osseous tunnels |

|

| Nerve near another structure |

|

| Nervous system is relatively fixed |

|

Clinical presentation

Typically double crush syndrome presents in similar patterns. For example:

- A golfer presents with “tennis elbow” and medial scapular pain.

- A rugby player presents with a hamstring strain and lower back pain.

- A cyclist complains of neck and elbow pain and numbness along the outside of the little finger.

- A long jumper complains of buttock and dorsal foot pain.

All of these are typical examples of patients with double crush syndrome. It is common for patients to describe two distinct areas of pain that do not appear to be connected. Often the onset of one area of pain precedes the other by weeks or months.

Nerve root compression pain is very specific, unremitting, and in a dermatomal distribution, often worse distally than proximally. In addition, with nerve root pain, there are commonly other neurological symptoms of numbness, pins and needles, and weakness.

The description of the pain associated with compromised neural mobility is different. It is non-specific and vague in intensity and distribution. It is not dermatomal and switches around from one area to another. Other neurological symptoms may or may not be present with neurodynamic pain.

On physical examination, neural tension tests will be positive. and tension points are tender. There will be some compromise to the mobility of the nerve in both or all areas that the patient describes in the subjective examination.

Poor posture is often a contributing factor. For example, forward head posture adversely affects the mobility of the nervous system. Therefore, posture correction in the workplace and during sports is important.

Aims of Physiotherapy Treatment

- Release centrally

- Release peripherally

- Restore full neurodynamics

- Correct posture

- Rehab, including slider and tensioner exercises

Physiotherapy management

1. Central joint and soft tissue mobilization

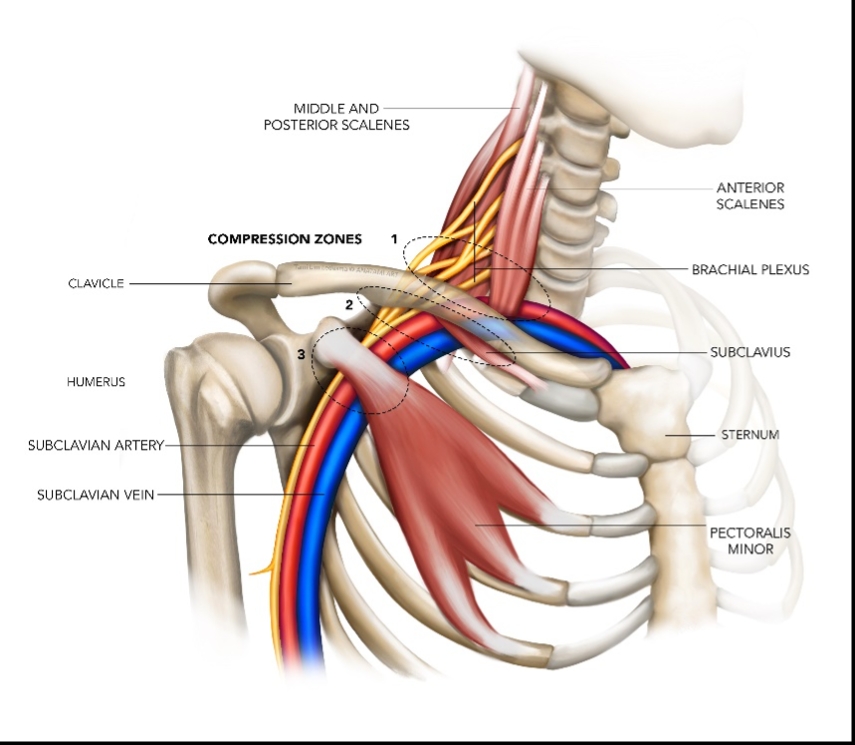

Clinicians can mobilize the central spinal regions to reduce the tension. Maitland accessory mobilization techniques are useful for improving the tiny glides and mobility at each motion segment. Anteroposterior (AP) unilateral mobilizations work especially well in the cervical spine to release neural tethering and restore neural mobility. Furthermore, any other spinal levels with known disc degeneration or spondylosis should be mobilized. For example, mobilizing the first rib and releasing the scalenes has a marked positive impact on brachial plexus mobility (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Structures that compress the brachial plexus

2. Peripheral joint and soft tissue mobilization

Clinicians should include myofascial release along the nerve path or the myofascial lines focusing on the soft tissue tension points. Specific soft tissue and peripheral joint mobilizations are valuable treatment techniques, especially accessory mobilization of joints like the wrist and superior tib-fib or radio-ulnar joints. Nerve mobilization is effective when nerves are superficial, like the superficial peroneal nerve.

For example, clinicians can use myofascial release and specific soft tissue mobilizations to release hamstrings. Starting with the hamstrings in a shortened position (prone with knee flexion) and progressing by increasing the stretch on the hamstrings changing the starting position until achieving full range with slump in side-lying (see video 1).

Video 1

Once the central and peripheral joints and soft tissues are mobilized, use the neurodynamic tests to ensure full neural mobility. Be sure to assess the neural mobility requirements of the specific sport (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Rugby player in full slump position while kicking the ball.

Related Files

Peripheral nerve mobilization: how to find piriformis

Find the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and the apex of the sacrum. Then find the spot on the sacrum halfway between those two points. Drop laterally off the sacrum. Draw an imaginary line between that point and the greater trochanter. Palpate along that line as the patient gently laterally rotates the thigh at the hip joint with the knee flexed to 90o (see video 1).

Conclusion

Reassessing the response to treatment helps with the diagnosis of double crush syndrome. Although athletes can present with vague symptoms initially, a thorough neural assessment is critical in identifying the possible entrapment sites. Treatment is successful if it addresses all the affected areas and restores the full mobility of the nerve. Clinicians should use clinical reasoning to identify the appropriate treatment techniques that meet the demands of the specific sport.

Reference

- Lancet. 1973 Aug 18;2(7825):359-62

- Health Jade - Double Crush Syndrome

- Grieve’s Modern manual therapy: the vertebral column, 2nd ed. 1994, Churchill Livingstone

- Mobilization of the nervous system, 1991, Churchill Livingstone

- Clinical Neurodynamics, 2005, Elsevier Health Sciences

- J Man Manip Ther. 2008; 16(1): 8–22

- The Student Physical Therapist - Neural Tension Points in the Body

- Physiopedia - Neurodynamic Assessment

- Man Ther. 2008 Jun;13(3):213-21

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.