You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Young Knees, Different Rules: Adolescent ACL Injuries.

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in young athletes are on the rise, yet treatment guidelines remain limited. Nicky van Melick and Stijn Geraets share insights on surgical treatment and rehabilitation.

Manchester City’s Matty Henderson-Hall in action with Leeds United’s Sam Chambers Action Images via Reuters/Jason Cairnduff

Over the past two decades, the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries among adolescents has increased dramatically. Girls aged 13 to 15 years face the highest risk, with a staggering 143% rise in incidence between 2000 and 2015. Boys also saw the largest increase in incidence in the same age group, though lower at 59%(1,2). Similarly, the annual number of ACL reconstructions in adolescents has grown, with an average annual increase of 2.2% in boys and 2.9% in girls (see figure 1)(3). Unfortunately, ACL revision rates are highest among those under 16, with approximately one in four requiring revision surgery, compared to one in ten adults(4,5).

Terminology

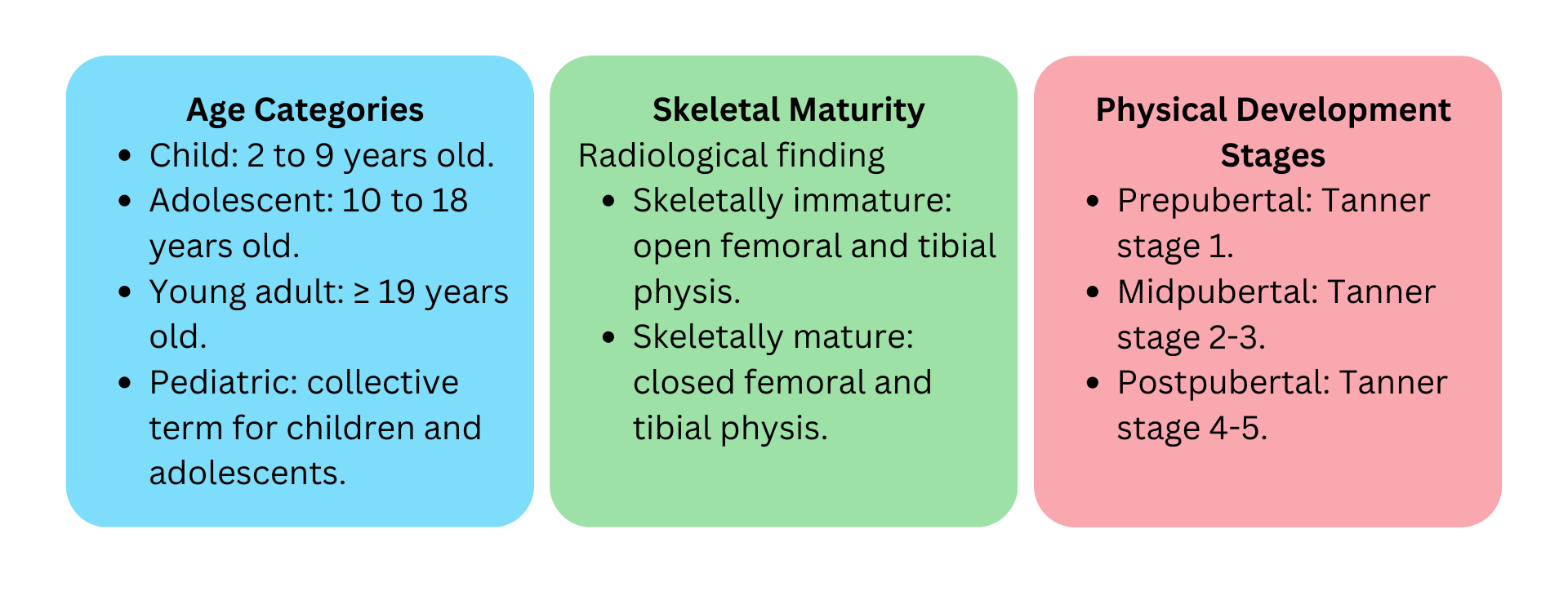

Clarifying terminology is key to identifying the correct group of athletes(6). There are varying perspectives from which different clinicians view childhood growth and maturation (see figure 2). The distinction between chronological age, skeletal maturity, and physical development is essential when managing young athletes. For example, orthopedic surgeons may focus on skeletal maturity, while rehabilitation specialists consider the athlete’s physical development stage.

Knee Trauma, Swollen Knee, and Pop Sign

Diagnosing ACL injuries in adolescents is considered more complex than in adults due to greater physiological joint laxity, difficulty in obtaining history, and unique adolescent differential diagnoses(7). Up to 65% of adolescents with a swollen knee within a day after trauma have an ACL injury(8). Additionally, a reported pop sign, as in adults, indicated a very high suspicion of an ACL injury(9).

Physical examination for ACL injuries mirrors that of adults, with the Lachman test, anterior drawer test, and pivot shift test showing high positive and negative predictive values when performed by an experienced orthopedic surgeon(9). Additionally, assessing the ability to extend the knee actively is crucial. Failure may suggest a patella sleeve or a tibial tuberosity avulsion fracture, both specific fractures for athletes in this adolescent age group(7).

A combination of knee trauma, a swollen knee within 24 hours, and a pop sign warrants (pediatric) orthopedic consultation and further assessment for ligamentous, (osteo)chondral, osseous, or meniscus injuries(7). Initial imaging includes a plain knee radiograph to check for tibial eminence and other fractures, followed by an MRI to confirm the diagnosis of an ACL injury and to evaluate other soft tissue structures(7). In addition to knee radiologic findings in pediatric patients, orthopedic surgeons may also use a left-hand X-ray to determine skeletal age.

Surgical Repair?

When clinicians confirm an ACL injury, they must consider treatment goals before discussing options with adolescents and their parents. The three primary treatment goals are:

- Restoring a stable, well-functioning knee that enables a healthy and active lifestyle throughout the lifespan.

- Reducing the impact of existing or the risk of further meniscal or chondral pathology, degenerative joint changes, and the need for future surgical intervention.

- Minimizing the risk of growth arrest and femur and tibia deformity(7).

Treatment options include rehabilitation alone or ACL reconstruction plus rehabilitation. The best treatment strategy remains a topic of discussion. Surgical ACL reconstruction is indicated if the adolescent has repairable associated injuries to the meniscus or cartilage, as isolated meniscus sutures or osteochondral fixation often fail in an unstable knee, potentially causing irreversible joint damage. Additionally, if the adolescent has no associated repairable injury, but the knee giving way persists after completing a rehabilitation program, surgery becomes necessary to prevent further harm(7).

About 50% of adolescents manage well with rehabilitation alone and bracing or modifying their sports participation(10). However, delaying ACL reconstruction increases the risk of secondary, possibly irreparable, meniscal tears(11). If the limitations of nonsurgical management are too restrictive, shared decision-making among the orthopedic surgeon, the adolescent, and their parents is essential to determine whether surgery is needed.

“Clear rehabilitation milestones help guide the progression of phases and decisions regarding return to

sport…”

Surgical Options

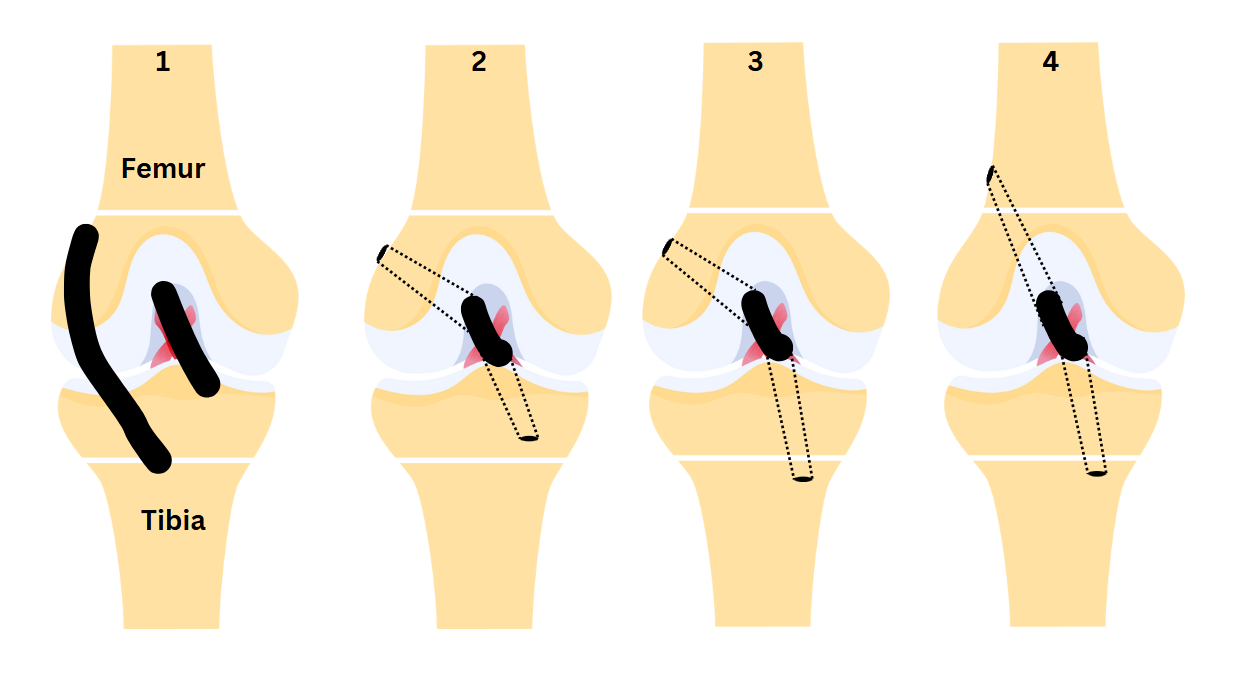

For adolescent ACL-injured knees with open femoral and tibial physis, surgical options include physeal sparing techniques like the over-the-top technique or the all-epiphyseal procedure. With increasing age, a femoral physeal-sparing technique can be combined with a tibial transphyseal technique. Near the end of growth, surgeons can use a physeal-respecting technique with a more vertical femoral transphyseal tunnel position (see figure 3)(12). The optimal technique for short and long-term outcomes remains uncertain.

Overview of pediatric ACL reconstruction techniques. Over the top technique (1); all epiphyseal technique (2); partial transphyseal technique, with all-epiphyseal femoral tunnel drilling (3); complete transphyseal technique with more vertical femoral tunnel position (4).

Rehabilitation

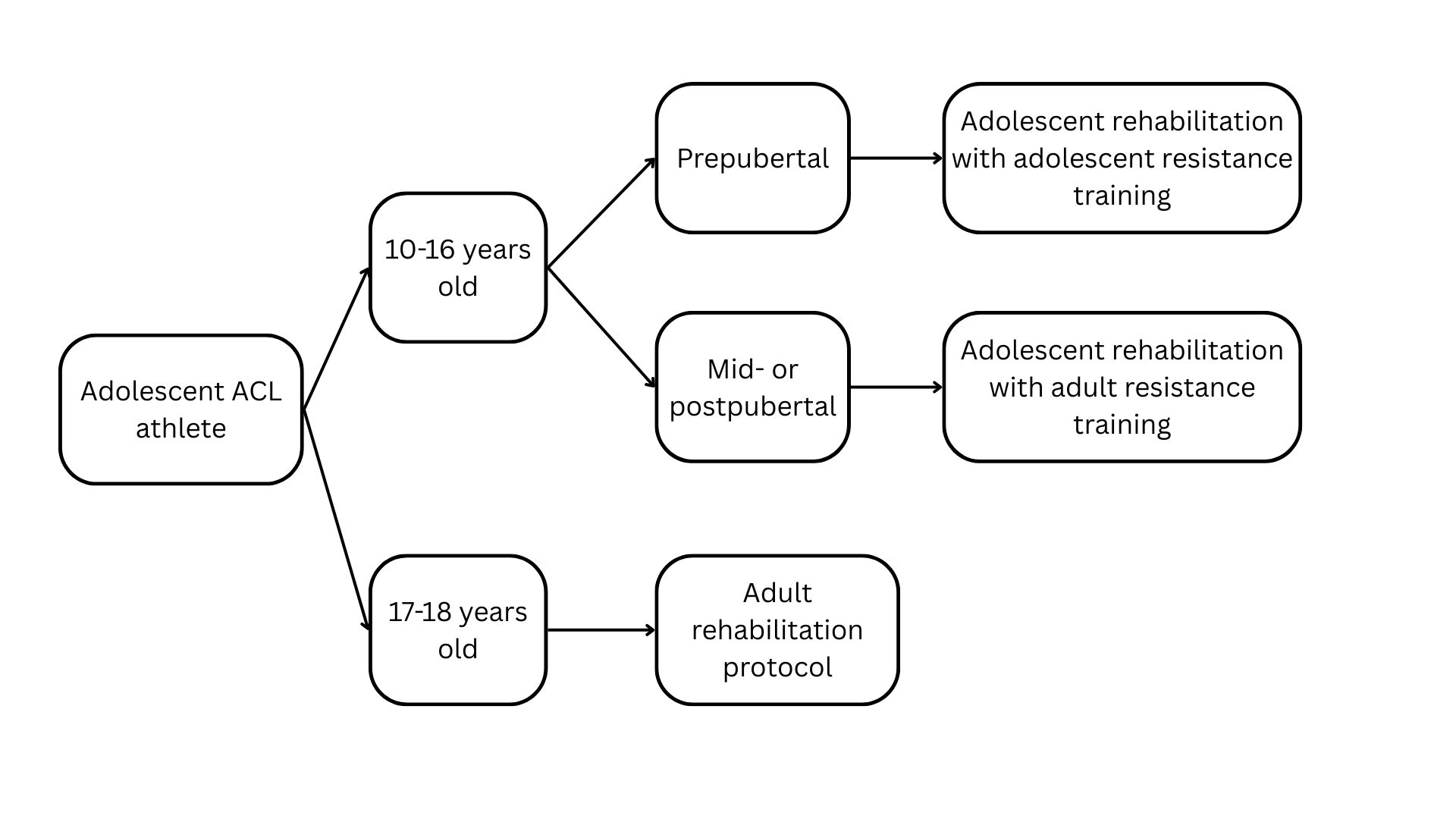

Whether non-surgical or postoperative, rehabilitation should be tailored to age and physical development stage. Using self-rated Tanner staging, clinicians can categorize adolescents as prepubertal or mid-to-postpubertal (see table 1). Girls assess breast growth and pubic hair, while boys assess genitalia and pubic hair. This simple, practical tool is widely applicable in sports medicine and has a strong association with the onset of puberty, specifically with the transition from Tanner stage 1 to stages 2-5(6,13).

Most 17- and 18-year-olds can follow adult ACL practice guidelines; however, a prolonged rehabilitation period of up to 12 months should be considered for this age group(6). For individuals aged 10 to 16, key differences from adult rehabilitation include a greater focus on neuromuscular training and movement quality, increased parental involvement, and a minimum 12-month rehabilitation period before returning to competition(6). Prepubertal athletes require further adjustments in resistance training and rehabilitation milestones(6).

Table 1: Self-rated Tanner Staging

| Stage | Boys | Girls | |

| Stage 1 |

|

|

|

| Stage 2 |

|

|

Onset of puberty |

| Stage 3 |

|

|

|

| Stage 4 |

|

|

|

| Stage 5 |

|

|

Resistance training

The first rehabilitation phase focuses on achieving a quiet knee (i.e., trace to no knee effusion, full passive and active knee extension, and quadriceps activation). It is a critical milestone, and clinicians should delay resistance training until the second phase to respect tissue healing(6). Prepubertal athletes lacking a puberty-driven hormonal increase in testosterone and estradiol experience slower strength gains, which can be attributed to improved intra- and intermuscular coordination. In contrast, muscle hypertrophy is more likely to play a role after the onset of puberty(14). Therefore, resistance training for prepubertal athletes should prioritize movement quality(6). Mid- to postpubertal athletes can follow adult resistance training programs(6).

Clinicians can progress the rehabilitation of prepubertal athletes as follows:

- Focus on functional movements with proper technique, using low loads and high repetitions (15-25).

- Introduce resistance training with an increased load, lower repetitions (<12), and a perceived exertion of 7 to 9 on a 10-point scale. Combine resistance, body weight, and plyometric exercises with fun and game-like elements, such as tempo variations, ball throws, and unstable surfaces(6).

Rehabilitation milestones

Rehabilitation milestones for phase progression and return to sport clearance are well-studied in adults. Most 17- and 18-year-olds and most mid- to postpubertal athletes can be tested using adult criteria, which assess clinical signs, neuromuscular control, and psychology.

However, prepubertal athletes, still developing motor control, struggle with traditional isokinetic strength and single-leg hop testing(6). While clinicians can adapt strength testing using belt-resisted handheld dynamometry or technological devices, identifying suitable neuromuscular control tests for jumping and hopping remains a challenge. Over the past year, our clinic has refined a test battery for prepubertal athletes, now recommending the following:

- Side slide test. Athletes slide sideways with one leg on a frictionless mat to a predefined knee flexion angle, with repetitions compared between legs.

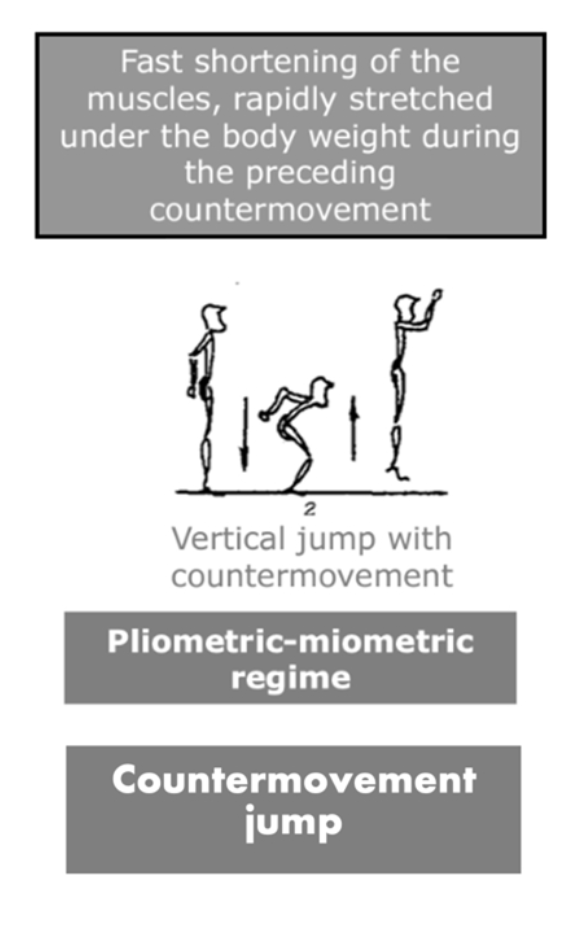

- Double-leg countermovement jump. Assessed on force plates or another validated technology, measuring jump height and force distribution (see figure 5).

- Forward single-leg hopping in a speed ladder. Five consecutive hops followed by a stable landing for three seconds. If the patient can perform the forward test, it is repeated in a zigzag manner, hopping in and out of the speed ladder.

- Side hop test. Ten rapid hops back and forth over a line. If the balance is lost, the test is repeated with the non-tested foot on a 30 cm playbox.

Athletes may use arm swings for propulsion or balance. A side note is that we have no follow-up data on reinjuries yet, and reference values must be established.

“Whether non-surgical or post-operative, rehabilitation should be tailored to age and physical development

stage.”

Conclusions

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in adolescent athletes are on the rise, and a tailored approach to treatment and rehabilitation is crucial, especially for prepubertal athletes. For these young athletes, resistance training primarily focuses on movement quality. Clear rehabilitation milestones help guide the progression of phases and return-to-sport decisions, although prepubertal athletes may require specialized tests to assess neuromuscular control. Ongoing research and refinement of these approaches are necessary, particularly regarding reinjury rates and standardized reference values.

References

- Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020 Feb;28(2):363-368.

- Sports Health. 2015 Mar;7(2):130-136.

- Med J Aust. 2018 May;208(8):354-358.

- Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arhtrosc. 2018 May;26(5):1362-1366.

- Am J Sports Med. 2019 Mar;47(3):628-639.

- Orthop J Sports Med. 2023 Jul;11(7):23259671231172454.

- Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arhtrosc. 2018 Apr;26(4):989-1010.

- J Child Orthop. 2023 Feb;17(1):4-11.

- BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022 Jul;23(1):710.

- Am J Sports Med. 2019 Jan;47(1):22-30.

- Am J Sports Med. 2021 Dec;49(14):4008-4017.

- J Child Orthop. 2023 Feb;17(1):12-21.

- J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Jun;32(6):569-576.

- Pediatrics. 2010 Nov;126(5):e1199-e1210.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.