You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Peace of Mind: Autoregulation Blood Flow Restriction

Blood flow restriction continues to grab the attention of sports medicine practitioners. However, the negative post-exercise consequences may prevent them from trying it out. Autoregulation BFR may provide the safety net that clinical practice requires to increase its implementation. Andrew Berry uncovers how it may enhance rehabilitation outcomes.

In today’s competitive environment, athletes are under increased pressure to perform well and avoid getting hurt. Blood flow restriction (BFR) is a new and improved training strategy resulting from the desire to maximize rehabilitation and performance outcomes. Athletes and practitioners can use a tourniquet cuff for purposes more than assisting with blood pressure measurements. Today, practitioners employ BFR technique to create a hypoxic condition in injured muscles to speed healing and strengthen the affected area. Blood flow restriction significantly improves muscle strength, endurance, and hypertrophy, which can be useful in managing injuries and training healthy athletes(1). However, there is still doubt about its optimal use in clinical practice as many factors influence the successful implementation, namely differences in equipment and methodologies(1).

To provide the same benefits as high-load exercise, blood flow restriction entails occlusion close to the target muscle or area, partially decreasing arterial blood flow, and occluding venous return(2). Training with BFR is conducted at low intensities (around 20-40% of max exertion) or low/medium intensities during aerobic exercises when targeting the cardiopulmonary capacities(3).

“Blood flow restriction therapy has shown promise in improving muscle strengthening and recovery.”

Furthermore, recent research on blood flow restriction has revealed additional insights into its potential benefits and applications. Researchers at the University of Tokyo investigated the effects of blood flow restriction on muscle protein synthesis (MPS) in older adults. They found that low-intensity resistance exercise combined with blood flow restriction significantly increased MPS in older individuals compared to exercise without restriction(4). These findings suggest that BFR may be particularly beneficial for older adults, who often face challenges maintaining muscle mass and strength.

Another area of interest is the potential role of blood flow restriction in accelerating post-injury recovery. In a study published in the Journal of Athletic Training, researchers examined the effects of blood flow restriction therapy on muscle recovery following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction surgery(5). The study demonstrated that BFR combined with traditional rehabilitation exercises resulted in greater quadriceps muscle size and strength than standard rehabilitation alone. Therefore, blood flow restriction may offer a valuable adjunctive treatment for athletes recovering from ACL injuries, allowing for a faster and more complete return to sport. These benefits, along with the low-load nature of BFR training, place less strain on the graft, cartilage, and meniscal and bone bruising injuries associated with the original injury(5).

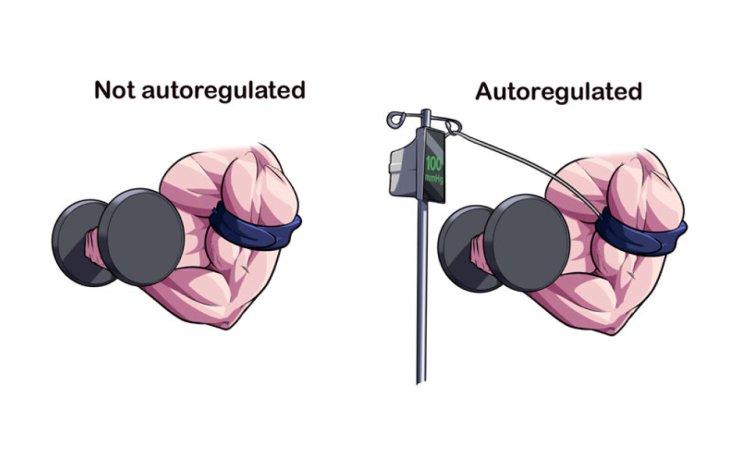

The newest advancement is the inclusion of autoregulation training into BFR protocols. Throughout the inflation cycle, autoregulation keeps the pressure in the cuff constant. When employing a non-autoregulated cuff, the muscle contracts and applies pressure to the cuff, which can result in a pressure spike, discomfort, a change in hemodynamics, and the release of air, which can then result in a reduction in the cuff pressure (see figure 1)(6). Thus, making autoregulated cuffs potentially safer and more effective.

Scientists from Ghent University in Belgium published one of the first papers investigating autoregulation as a primary variable(7). Their study showed a three-fold reduction in the risk of minor adverse effects such as light-headedness, indicating a safer protocol. Increasing repetitions with less delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) with similar blood pressure responses could result in more significant strength gains due to the athlete’s ability to do more with less recovery. The autoregulated cuff has many desirable outcomes and decreased perceptual demands during the exercises(6).

In the United States, researchers showed that while traditional (without BFR) and non-autoregulation training increase central arterial stiffness, autoregulation BFR training did not influence it. Furthermore, supporting the positive effects of autoregulation in BFR was the increase in cross-sectional area and echo intensities in non-autoregulated BFR groups. This suggests a lower fluid flux to intracellular cells, reducing muscle damage and swelling when using autoregulation BFR(8).

“Establishing uniform BFR training protocols across various demographics and exercise modalities is essential to maximize outcomes and guarantee safety.”

Although there appear to be many advantages to utilizing autoregulation in BFR, the results may be transient. A systematic review from Spain noted improved pain threshold, functionality, and quality of life in neuro-musculoskeletal patients during the first six weeks; however, results are less clear for medium- and long-term interventions(2,7).

Several areas still need more research, despite the growing support. For instance, researchers are yet to identify the long-term consequences of prolonged or excessive BFR. Establishing uniform BFR training protocols across various demographics and exercise modalities is essential to maximize outcomes and guarantee safety(1).

Blood flow restriction therapy has shown promise in improving muscle strengthening and recovery. Athletes, practitioners, and researchers have all noticed it due to its ability to reproduce the advantages of high-load exercise and induce a hypoxic state in injured muscles. Autoregulated cuffs have demonstrated potential benefits in effectiveness and safety, minimizing side effects, and improving training results. Practitioners can expect BFR to continue to change how they approach muscle healing, injury prevention, and sports training, as it can potentially change the field of rehabilitation and performance. Autoregulation may give practitioners the peace of mind to implement it in rehabilitation and reduce fears around the negative short-term consequences.

References

- CMBES (2023) Blood flow restriction therapy: The essential value of accurate surgical-grade tourniquet autoregulation

- Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 20(2), p. 1401 (2023)

- J. Ex. Sci. Fit., 20(2), pp. 190–197 (2022)

- J. App. Physiol, 108(5), pp. 1199–1209. (2010)

- Techniques in Orthopaedics, 33(2), pp. 106–113

- Bri. J. Sports. Med. (2023)

- Front. Physiol. 14:1089065

- Rolnick, N. et al. (2023) [Preprint]. doi:10.51224/srxiv.253

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.