You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in the Female Athlete

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a common yet often overlooked condition affecting female athletes, with symptoms such as urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and chronic pelvic pain. Corlia Brandt explores how high-impact sports may place stress on the pelvic floor muscles and how clinicians can be better placed to guide athletes.

Germany’s Marlene Meier, Rayniah Jones of the U.S., and Germany’s Rosina Schneider in action during the women’s 60m hurdles REUTERS/Axel Schmidt

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) includes but is not limited to urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, sexual dysfunction, and chronic pelvic pain. Approximately 40-60% of all women suffer from PFD during their lifetime. However, it is under-reported, under-recognized, and under-treated in female athletes. High-impact, repetitive sports can put women at risk for developing PFD(1). Urinary incontinence is common in female athletes, and the prevalence in female nulliparous athletes can range between 5-80%, with the highest prevalence in women participating in high-impact sports. Researchers at the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro in Portugal reported that the prevalence of UI among female athletes was 25%, and stress urinary incontinence was 20%(2). The prevalence in high-impact sports was 25%, with the highest prevalences observed in the following sports: volleyball (75%), trampolining (72%), indoor soccer (50%), cross-country skiing (45%), running (44%), basketball (34%), athletics (20%), and handball (20%)(2). However, the risk for PFD increases in women after pregnancy and when aging due to other causative factors starting to play a larger role, such as hormonal changes and BMI, amongst other factors.

“Educating healthcare professionals is the first critical intervention in improving the management of athletes with PFD.”

Mechanisms

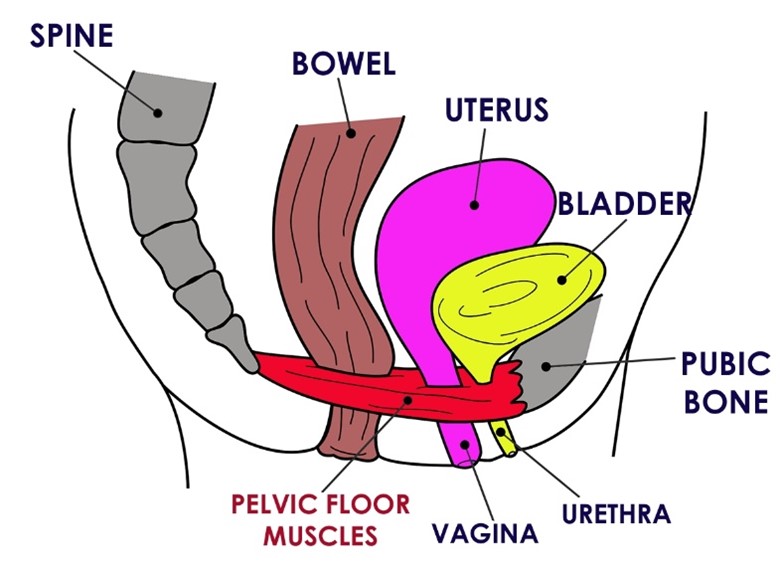

The pelvic floor works in coordination with the stabilizing muscles (the diaphragm, abdominal muscles, and back muscles such as the Multifidus muscle) to ensure effective force transmission and spinal support to withstand the forces, maintenance of posture, and dynamic stabilization (see figure 1).

High-impact activities are “those involving the performance of several jumps and actions related to maximum abdominal contractions” and clinicians classify them into three grades(3):

- Impact grade 3 (>4 times body weight, such as jumping activities);

- Impact grade 2 (2–4 times body weight, such as sprinting activities and movements involving rotation);

- Impact grade 1 (1–2 times body weight, such as light weight lifting);

- Impact grade 0 (<1 times body weight, such as swimming).

The increase in intra-abdominal pressure exerts an impact force directly on the pelvic floor muscles (PFM)(1,4,5). Running, jumping, and landing increase intra-abdominal pressure exerted onto the pelvic organs and tissues, making them susceptible to tissue failure or injury associated with PFD(6).

“Pelvic floor dysfunction among female athletes is multifactorial…”

There are multiple possible reasons and mechanisms why high-impact activities may lead to PFD in female athletes. The first hypothesis is that athletes, under normal circumstances, should have strong pelvic floor muscles. Strenuous exercise may increase abdominal pressure, creating a simultaneous or pre-contraction of the PFM. This mechanism, in turn, may act as a stimulus during training of the PFM(7). The second hypothesis contradicts the first, as a recent systematic review indicated that strenuous activity (which causes a chronic or repeated increase in abdominal pressure) may stretch, overload, weaken, and eventually lead to pelvic floor failure.

Researchers at the University of Porto in Portugal found that an incontinent group of athletes had a thicker pubovisceral muscle at the mid-vaginal level, contradicting the hypothesis that stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is associated with the displacement or strength of the PFM(8). A decreased or delayed response of the pubovisceral muscle may explain these findings. The PFM thickens to counteract the decreased responsiveness of the sphincter urethrae. An extended sports training history may support the hypothesis of changes occurring in the intrafusal fibers(8).

Clinical Takeaways

Routine screening: Proactive screening should be integrated into sports medicine assessments to identify at-risk individuals.

Comprehensive assessment: Clinicians should evaluate PFM strength and endurance, coordination, and contributing biomechanical factors such as kinetic chain imbalances, hormonal influences, and past medical history.

Individualized treatment: Management should be tailored to the athlete’s specific needs.

Awareness: Athletes, coaches, and healthcare professionals must be educated on PFD symptoms, risk factors, and management options to reduce stigma and encourage early intervention.

Conservative management: Clinicians should prioritize non-surgical interventions and address contributing factors before considering surgical options for severe cases.

Alternatively, the high forces produced by high-impact activities may cause injury during transmission through the tissue. Should the affected tissue not be treated after injury, it may remain malformed and dysfunctional, increasing the risk of further dysfunction(9). The dysfunction may lead to failure of the continence mechanism due to the muscular force transmission to the urethra being affected. In addition, the PFM may become fatigued due to the repeated intra-abdominal pressure experienced during the sporting activity, which may further lead to malfunctioning of the continence mechanism.

“Early identification through screening, education, and athlete-centered management is crucial...”

Genetic predisposition has also been postulated to be a risk factor for PFD in female athletes, similar to the general female population. Furthermore, differences in individual athlete fatigue levels may impact their capacity to manage high-impact sports demands. Every female athlete may have a different personal fatigue level. When this fatigue level is reached, the continence mechanism may malfunction(10).

There is a higher prevalence of leakage in athletes during training compared to during competition (95.2% vs. 51.2%). It is postulated that higher catecholamine levels during competition may be the reason for this. The catecholamine acts on the urethral α-receptors to maintain its closure during activities at the competition level(11). Moreover, low body mass index (BMI), low energy availability (RED-s), estrogen changes, and hypermobility joint syndrome may contribute to the development of PFD in female athletes. Lastly, the problem may occur in conditioned athletes at the muscle spindle level. Repeated or sustained increased intra-abdominal pressure may stretch or lengthen the pelvic floor muscles and affect the function and responsiveness of the intrafusal muscle fibers over time(1).

Clinical Implications

Educating healthcare professionals is the first critical intervention in improving the management of athletes with PFD. Coaches and clinicians must understand the signs, symptoms, and management options available to athletes to guide them appropriately if they report challenges and seek treatment. However, athletes are unlikely to report PFD symptoms. Therefore, screening is the best way to identify athletes at risk. Together with screening, preventative measures should also be taken in young female athletes, especially those with RED-s.

Pelvic floor dysfunction among female athletes is multifactorial, and conservative management is the first line of treatment. Clinicians should assess athletes for contributing factors and manage the whole athlete instead of only their presenting PFD symptoms. This may include factors such as imbalances in the closed kinetic chain or stabilizing mechanisms, muscle endurance, strength, other injuries or pain, medical factors, and genetic predisposition. A comprehensive assessment will identify contributing factors. This includes a detailed interview with the patient, establishing their medical and gynecological history.

In addition, clinicians can perform several physical tests, such as establishing the strength, tone, activity, control, and level of function of the PFMs and the surrounding muscle groups. Assessment may include manual palpation, rating scales such as the modified Oxford rating scale, testing with a perineometer or dynamometry, standardized questionnaires, electromyography, ultrasound, or another specialized bladder testing (such as urodynamics)(11). Importantly, PFM strength may not necessarily be the only factor to consider in athletes – although it cannot be ruled out until clinicians establish a differential diagnosis.

Addressing the contributing factors should be through a tailored and athlete-specific PFM training program, ensuring that the issue at hand (such as endurance, muscle control, strengthening of a lengthened muscle, amongst others) is being addressed and conservative management achieves optimal outcomes. In more severe cases, surgery might be indicated to restore normal bladder function.

Pelvic floor dysfunction in female athletes is a complex issue that is often overlooked despite its prevalence. Early identification through screening, education, and athlete-centered management is crucial for mitigating the long-term effects. Clinicians and coaches need to recognize the signs of dysfunction to provide appropriate, evidence-based interventions. Conservative treatments, like individualized pelvic floor muscle training, should be prioritized, with surgical options considered only in severe cases. Increasing awareness and proactive management can help female athletes maintain performance and pelvic health.

References

- The Physician and Sports Medicine, 45, 399 - 407.

- Journal of Human Kinetics, 73, 279 - 288.

- JBMR Plus, Volume 8, Issue 11, November 2024, ziae119.

- Rev Bras Med Sports, 2011; 17: 97-101.

- International Urogynecology Journal, 29, 1717-1725.

- J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021 Jan 28;6(1):12.

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(7):870-6.

- Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 25, 270–275.

- Springer, London. doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84628-756-5_25

- Scandinavian J of Med & Sci in Sports. 15. 87-94.

- Br J Sports Med. 2014 Feb;48(4):296-8.

- Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2021; 40: 1217-1260.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.