You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Advising on Youth Athletic Development

As youth sports participation increases, so do the physiological and psychological demands. Jason Tee conveys the most up-to-date research on best practices in youth athletic development to equip clinicians to consult and advise on appropriate levels of competition and exposure.

Kids participate in soccer skill lessons from Crew Youth coach Hazem Sobhy during the MLS All-Star Community Day. Mandatory Credit: Adam Cairns-USA TODAY Sports

By any measure, sports participation is a young person’s pursuit. Data from Australia indicates that two-thirds of the sport’s participants are under 20(1). Similar data from the UK shows that only a third of adults over 25 participate in a sports session once per week(2). Participation numbers in sports are dramatically skewed towards youth participation. Hence, it makes sense that a large proportion of the injuries that we see and treat are among young sportspeople.

But that is not all that is going on. With popularity comes opportunity, and youth sports are a booming business. In the USA, the youth sports industry was estimated to have a total value of $39.7 billion in 2022, with projections that this will increase to $69.4 billion by 2030(3). It should be positive that so much investment in youth sport and physical activity is taking place, but as with all industries, there is the risk that the exponential growth bubble leads to too much too soon. We are far from the world of wholesome pick-up games with flat footballs in local parks. Instead, clubs and academies compete to attract participants with more elaborate training programs and competition structures. It is not uncommon these days for seven-year-olds to participate in travel sports teams and compete in different states each weekend.

Injury is a factor in all levels of sports participation. Still, when sports organizers are injudicious in their planning and exposure of youth athletes, injury rates increase, and sports injury professionals are often left to rehabilitate and advise on what is appropriate.

“...young participants do not progress to highly structured and specialized sports involvement until at least their mid-teens!”

Youth Athletic Development

Academic researchers dedicate themselves to describing the optimal pathways for youth athletic development. These models explain what activities should take place at what stages of the development pathway. While some top performers deviate from these models, it’s a much safer bet to stick to the guidance. Importantly, the endpoint for any youth athletic development model is life-long participation in sports and physical activity. Still, elite competition is a step on the development pathway that some participants may be able to access.

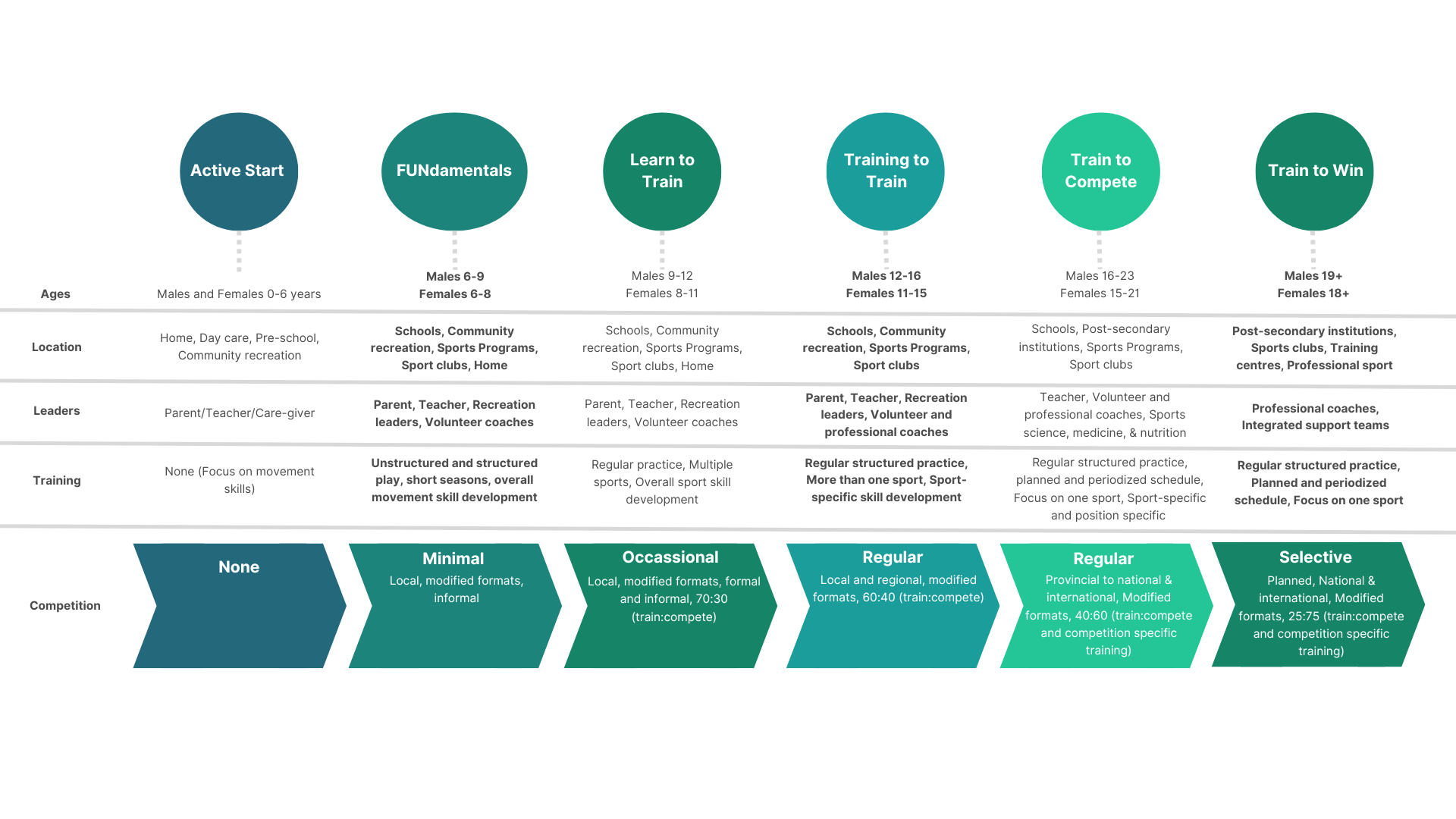

The pioneer in this space was Canadian researcher Istvan Balyi, and his seminal work remains the most referenced and cited research in this space(4). Balyi’s Long-Term Athletic Development (LTAD) model divides the sporting development pathway into six clearly defined stages. He describes each stage in terms of age-appropriate training goals and activities that guide coaches and administrators to what is ideal for development at each stage (see figure 1). To draw an obvious contrast, the current travel sports phenomenon in the USA and the emergence of highly specialized football academies in the UK and other European countries are significant deviations from this proposed model.

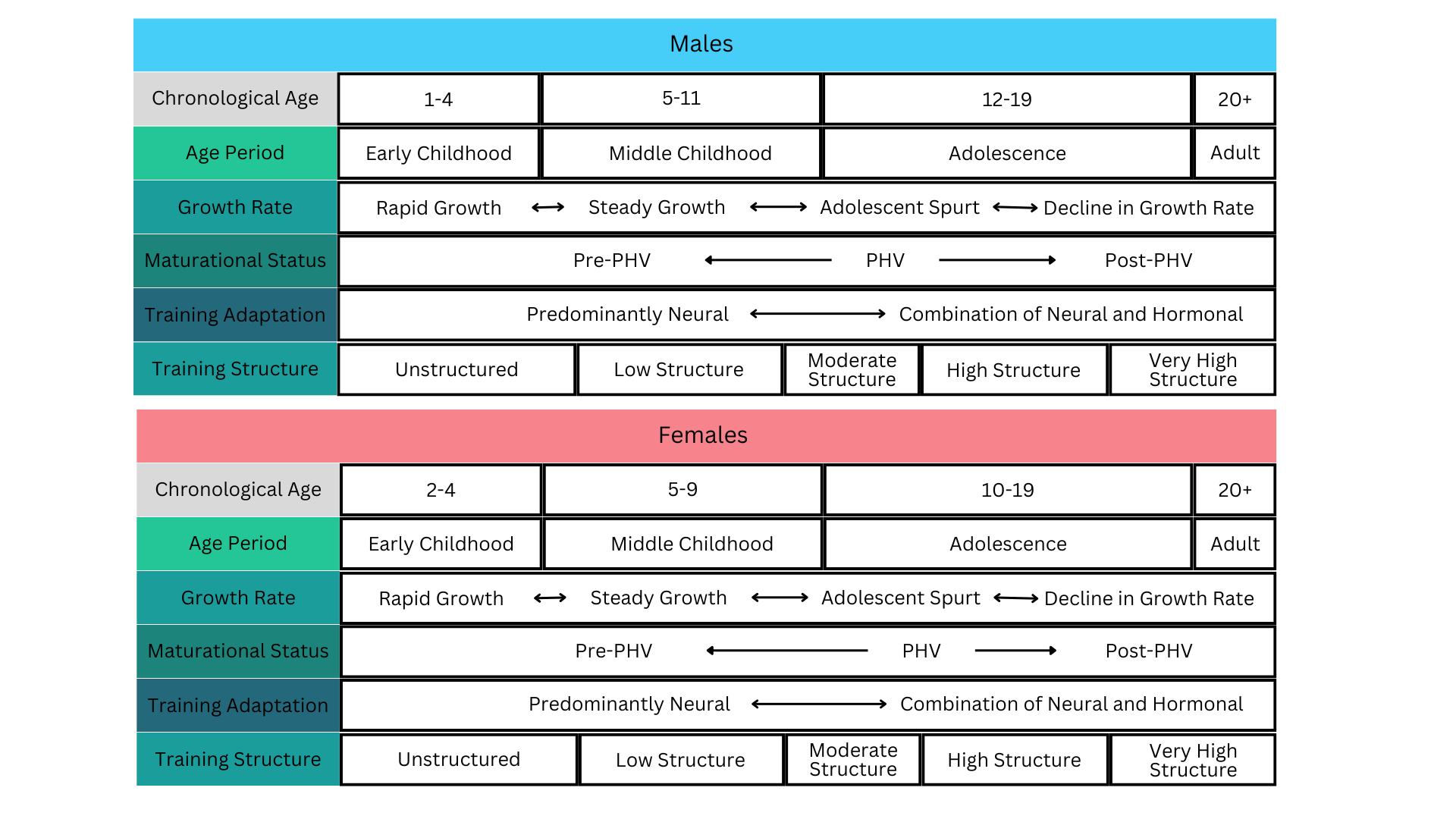

The other highly recognized youth athletic development model is Rhodri Lloyd and Jon Oliver’s Youth Participant Development (YPD) model (see figure 2)(5). Published almost 10 years after Balyi’s LTAD model, the YPD benefits from a more modern understanding of physical development in terms of proximity to the adolescent growth spurt rather than being purely based on chronological age. In addition, the YPD model emphasizes that a broad range of activities are important across the sports participant’s life span, but with differing emphasis at different stages. In contrast, the LTAD model talks about “windows of opportunity”, implying that if a particular window is missed, this would be detrimental to long-term development.

“Children with a healthy foundation of fundamentals will cope easily with this transition.”

While there are some differences between these two highly regarded models, there are also several similarities. Both suggest that sports participation should progress from unstructured and community-based sports in younger years to progressively more competitive and structured programs for teenagers. Both also strongly recommend involvement in multiple sports and seasonal participation during younger years, with structured, full-time involvement with a single sport only being recommended in later teenage years. These principles are further reinforced in the International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development(6). As a sports injury professional, there is a weight of scientific evidence to support that recommendation that young participants do not progress to highly structured and specialized sports involvement until at least their mid-teens!

“As sports injury professionals, we must advocate for good practice in these spaces.”

Early vs. Late Specialization

One of the key risks identified of injury in youth sports participants by the IOC consensus statement is taking on too much training too soon. On the other hand, youth sports organizations (clubs, academies, etc.) often recommend increasing involvement, with the main argument being that children will fall behind if they don’t have the same training and competition opportunities that others. This overly simplistic interpretation of talent development assumes that progress is linear and that if a participant is not at a certain level at a certain stage they can’t progress. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The youth sports program marketers will never tell parents that less is more in their industry – but the evidence tells that story.

Talent identification is notoriously difficult. There are large incentives for sports organizations to be able to identify the best talent at the youngest possible age. As a result, significant research has gone into this field. Despite the best intentions, the consensus is that talent ID is affected by many factors and that the best strategy to increase your success rate is to wait as long as possible before selection(7).

A 2010 study of athletes from Denmark provided some interesting contrasts between athletes who ultimately became elite (top 10 at a world championship event or top three in a European championship event) versus those who were merely very good (selected to represent Denmark). Their finding showed that the athletes who became elite spent fewer hours training for their sport in their younger years and committed to full-time training in their sport at a much later age than those who were near-elite. Patience pays off in athletic development.

A further factor to consider is that early success in sports rarely translates into success at an adult level. The sport of athletics is useful to consider because there is extensive, objective data on the performances of youth versus senior athletes. Less than a quarter of athletes ranked in the top 100 in the world at the U18 level ever make it into the top 100 at senior level(9). This falloff becomes even larger if younger athletes (U16) are considered. A meta-analysis of the performance of 13,392 athletes established that only 2.2% of the variance in performance in senior-level athletics is explained by performance at junior levels(10). Categorically, no one needs to be a world champion at 12 to have an opportunity to have a professional sporting career.

A final compelling study to consider is the work done by a German research group investigating the development of top-level German soccer players(11). Germany won the World Cup in 2014, and 18 national players from that generation are represented in this study. The researchers found that compared to amateur football players, the international players played more non-organized leisure football in childhood, engaged in other sports in adolescence, and specialized in organized football only at 22+ years of age. The rush to early involvement in competitive sport must be considered ill-informed at best.

What should training look like?

Now that some of the myths about youth sports have been debunked, sports injury practitioners should feel confident to have an informed discussion with parents or athletes in their care about what is unnecessary. But what is necessary? While I’m sure you agree that highly structured sports practices at a young age aren’t essential, no exposure would lead to no development, and that also wouldn’t be optimal.

Time commitment

Two simple rules of thumb are:

- No one should be exposed to more weekly hours of organized practice than they are years old,

- Everyone should have one day per week where they don’t participate in any structured sports practice.

Outside these guidelines, children can play for as long as they wish, but this playtime should be unstructured and self-guided.

Practice content

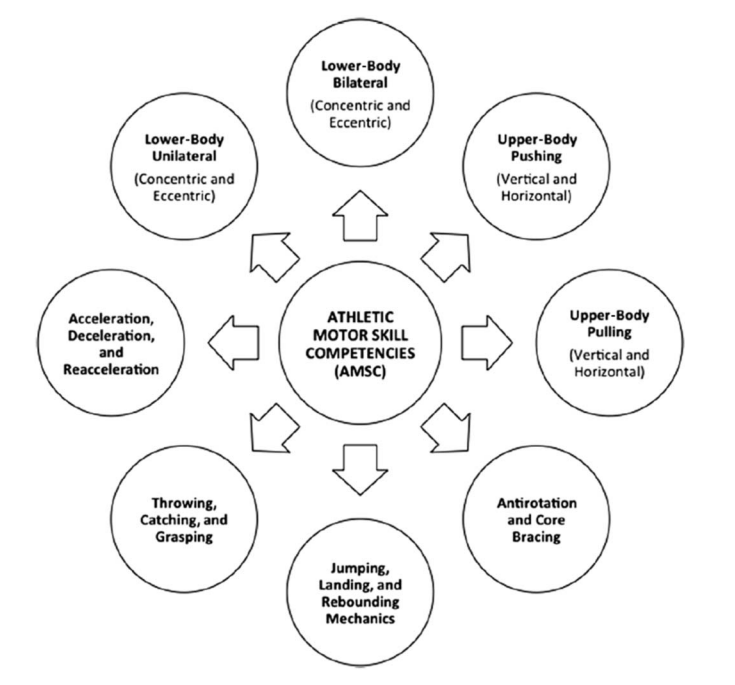

Both the LTAD and YPD models presented significant time spent developing “Fundamental Movement Skills” – but what are these? The most useful interpretation to explain these is Stability, Object Control, and Movement Skills (see figure 3). The goal of any sporting curriculum for children up to 12 should be to develop a broad range of competency in these skills. Stability, Object Control, and Movement Skills, when linked and combined, are the foundation of any skillful athletic movement. Younger participants will need to practice skills in isolation, while older participants should be encouraged to link, combine, and refine these skills during training.

In the early teenage years, the emphasis on sports shifts towards regular structured practice, and as a result, there is more focus on sport-specific skills. Children with a healthy foundation of fundamentals will cope easily with this transition. During this development phase, at least 60% of training time should focus on technical and tactical aspects of the game. Physical outputs are also important at this stage, and physical training should focus on developing athletic movement competencies (see figure 4)(8). Athletic movement competencies are an athlete’s ability to perform basic movement tasks with satisfactory biomechanical alignment, stability, and efficiency – effectively applying these skills combined with sports-specific skills and tactical understanding will drive competitive performance. Other important considerations at this stage are mental preparation for competition and how to engage socially with the team, coaches, and other support. In the early teenage years, we learn the habits that might support later performance.

Summary

While the participation of young people in youth sports and physical activities is undoubtedly positive, there is the risk of having too much of a good thing. Overzealous sports organizers and parents hoping to give their children the edge often throw caution to the wind and commit to ever more demanding playing and practice schedules. As sports injury professionals, we must advocate for good practice in these spaces. Sports practitioners are often left to manage and rehabilitate overuse injuries, which provides an excellent opportunity to educate players and parents alike on what is age-appropriate. Children are not just “small adults,” and they have specific needs and opportunities for development that should be fulfilled by the sports programs they are enrolled in. This data arms clinicians with facts and figures that will allow them to advocate for best practices in these spaces.

References

- BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2016 Mar 12:8:6.

- Adult participation in sport: Analysis of the Taking Part Survey. 2011 August. Department for culture media and sport. assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7b483bed915d3ed90635e6/tp-adult-participation-sport-analysis.pdf

- Sports Events and Tourism: STATE OF THE INDUSTRY REPORT (2021) Sports and events tourism association

- Olympic coach. 2004;16(1):4-9.

- Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2012 June 34(3)

- Br J Sports Med. 2015 Jul;49(13):843-51.

- Front Psychol. 2020 Apr 15:11:664.

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011 Dec;21(6):e282-90.

- Front Psychol. 2022 Jun 2:13:869637.

- Sports Med. 2024 Jan;54(1):95-104.

- Eur J Sport Sci. 2016;16(1):96-105.

- Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2020 Dec 1;42(6):54-70.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.