You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Update: Understanding Adductor Strains

Adductor injuries continue to plague athletes in multiple sporting codes. Measuring symptoms, strength, and performance can assist with early detection, monitoring, and rehabilitation. Lindsay Harris provides a clinical update on adductor-related pain.

Arsenal’s Beth Mead scores their third goal Action Images via Reuters/Paul Childs.

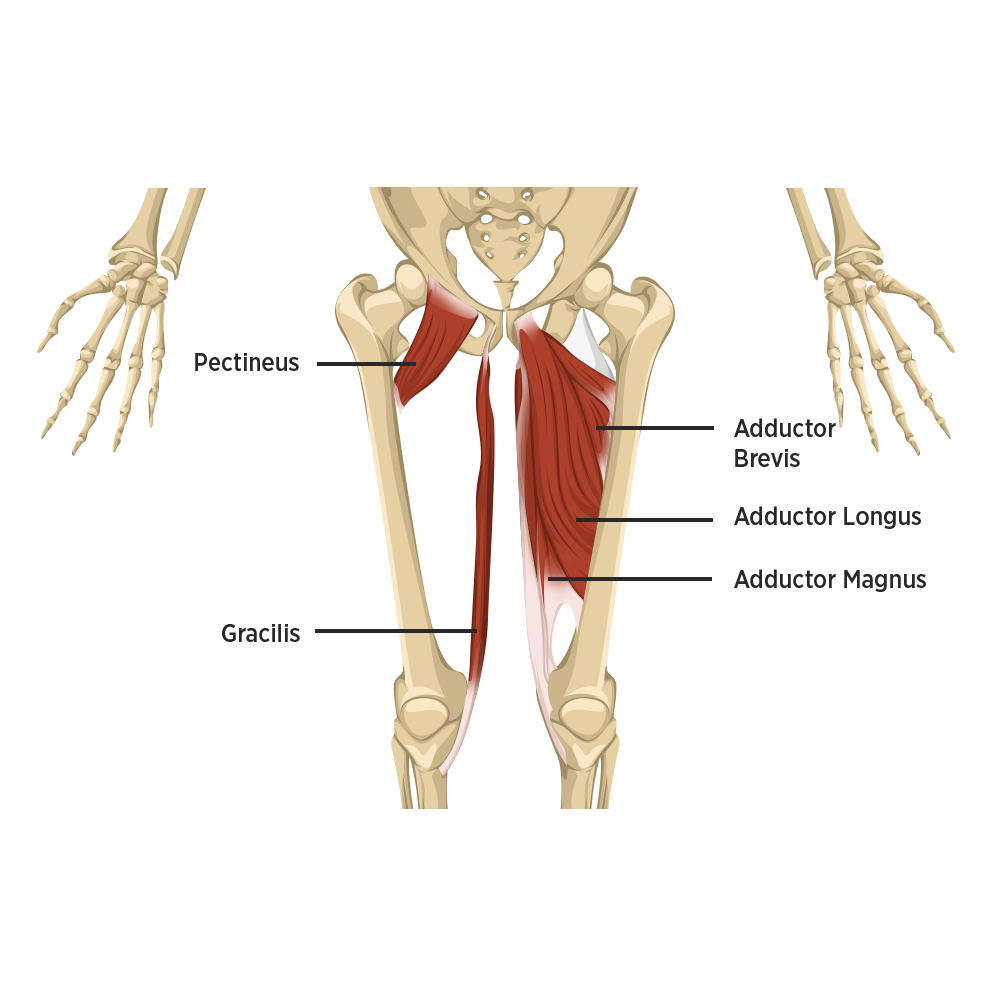

Hip adductor muscle and tendon injuries are the most common problems in athletes presenting with both acute and long-standing groin pain(1,2). The adductor complex includes the three adductor muscles (longus, magnus, and brevis), and the adductor longus is most commonly injured(3). The adductors have multiple functions. Adductor longus provides some medial hip rotation, whereas adductor magnus functions during hip extension due to its attachment to the ischial tuberosity. Notably, in open-chain activation, they function primarily as hip adductors. However, in closed-chain activation, they stabilize the pelvis and lower extremity during the stance phase of gait. Moreover, they have secondary roles, which include hip flexion and rotation.

This way, the adductors almost work as scissors and a bilateral force couple during sprinting, kicking, and skating. Depending on the sport, they have a critical stabilizing function and primary movement role in different specific and repetitive movement patterns. Due to their roles, they are highly involved in sports that include kicking, skating, and direction change(1).

Diagnosis

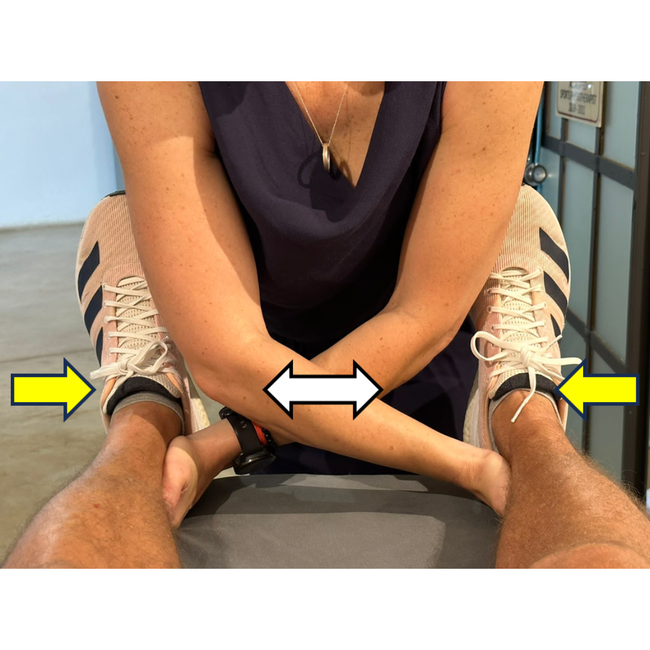

A detailed subjective examination, including the mechanism of injury, is key in the clinical examination of adduction injury athletes. In the objective examination, clinicians should follow the basic guidelines of “look, feel, and move.”. Visual inspection of the groin and thigh may reveal a hematoma from an acute adductor rupture, which may track all the way down to the popliteal fossa(2). Palpation of the adductor longus tendon insertion may reproduce the patient’s symptoms, especially in long-standing and adductor-related groin pain(4). Most injuries to the adductors, acute or overuse, involve the superior part of the adductor longus tendon and its insertion (up to 70% of all groin problems)(3,4). Clinicians must include pain provocation tests, including muscle contraction against resistance, stretch (leg abduction), and palpation. Adductor-related pain is confirmed if the clinician reproduces the athlete’s pain via isometric adduction squeeze performed on straight limbs together with a tenderness on palpation of the adductor longus muscle (see figure 2)(4). Furthermore, clinicians can request other investigations, including ultrasonography and MRI, when suspecting other structures.

Mechanisms of Injury

In most cases, the acute adductor strain occurs in the myotendinous junction. However, it can also involve other musculotendinous structures and connective tissue. The tendon may be the injury site or the enthesis where it inserts into the bone(5). These happen with forceful movements, including kicking, direction change, and other movements that involve the muscle being stretched during a forceful contraction - essentially a “reach” of the lower limb (see figure 3).

Clinicians must note that hip adductor forces change significantly during adolescent growth. This tends to increase the stress on the adductor muscle-tendon complex. A combination of growth changes, together with eccentric muscle demand or changes in load on the adductor muscles, their insertional area, and pubic bone, make this group vulnerable to apophyseal overload and overuse problems(2).

Long-standing problems tend to have an overuse pattern(2). It is difficult for clinicians and athletes to determine a single trigger, but there is typically a change. Change in activity level, playing style, or technique. Clinicians must ask in-depth questions to identify the possible changes that will add to their clinical judgment.

Adductor-Related Risk Factors

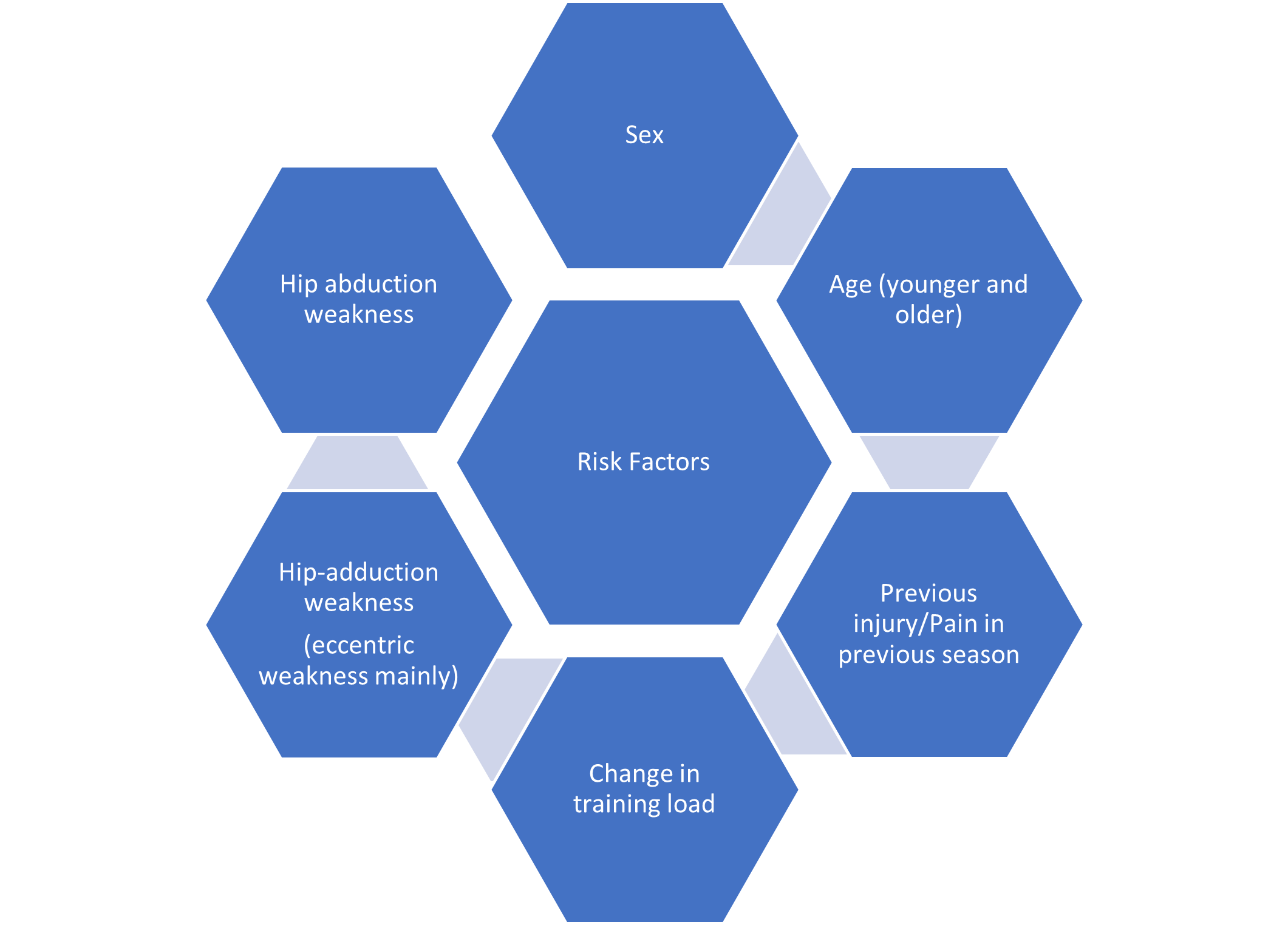

Risk factors for developing groin problems include sex, age (older and younger), previous injury, pain in the last season, and hip-abduction weakness (see figure 4)(6). Changes in training load, typically seen during the preseason, are also a risk as they result in rapid changes in training volume.

In male athletes, an eccentric hip-adductor-to-abductor strength ratio of <0.8 is associated with an increased risk of hip adductor strains in ice hockey. A weak eccentric strength (> 1 SD below the mean) and poor hip-adductor squeeze test strength increase the risk for adductor-related groin pain in soccer. However, this is not consistent across all sporting disciplines(6).

Italy’s Matteo Arnaldi in action during his singles match against Australia’s Alexei Popyrin REUTERS/Jon Nazca.

Clinicians must note that hip adductor forces change significantly during adolescent growth. This tends to increase the stress on the adductor muscle-tendon complex. A combination of growth changes, together with eccentric muscle demand or changes in load on the adductor muscles, their insertional area, and pubic bone, make this group vulnerable to apophyseal overload and overuse problems(2).

Long-standing problems tend to have an overuse pattern(2). It is difficult for clinicians and athletes to determine a single trigger, but there is typically a change. Change in activity level, playing style, or technique. Clinicians must ask in-depth questions to identify the possible changes that will add to their clinical judgment.

Adductor-Related Risk Factors

Risk factors for developing groin problems include sex, age (older and younger), previous injury, pain in the last season, and hip-abduction weakness (see figure 4)(6). Changes in training load, typically seen during the preseason, are also a risk as they result in rapid changes in training volume.

In male athletes, an eccentric hip-adductor-to-abductor strength ratio of <0.8 is associated with an increased risk of hip adductor strains in ice hockey. A weak eccentric strength (> 1 SD below the mean) and poor hip-adductor squeeze test strength increase the risk for adductor-related groin pain in soccer. However, this is not consistent across all sporting disciplines(6).

Clinical Management

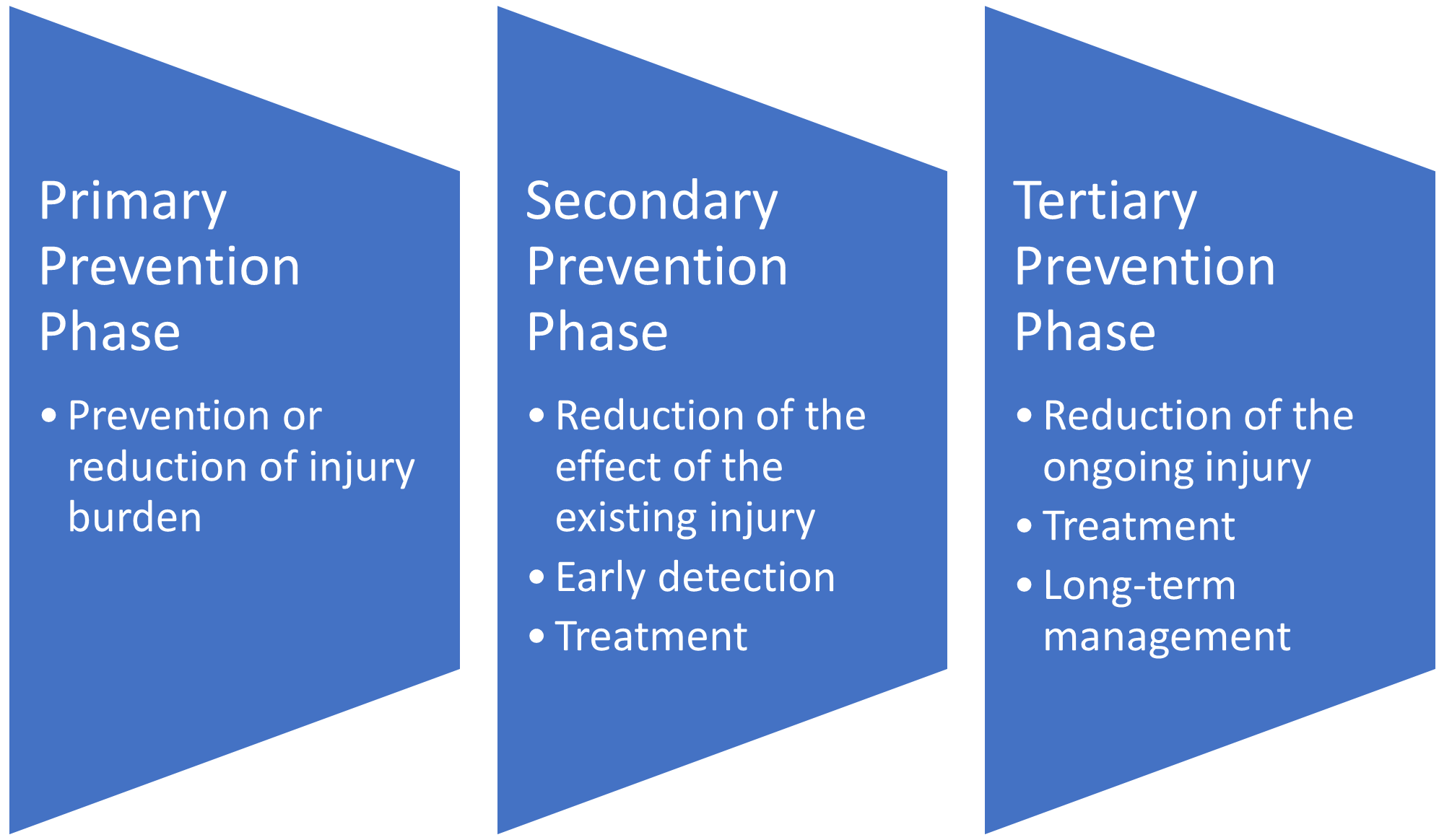

Clinicians must implement injury prevention programs to address these complex injuries. In the primary prevention phase, the focus is on preventing or reducing the injury burden. The secondary phase aims to reduce the injury effect after it has occurred by detecting and treating it as soon as possible, thus preventing any injury progression. Finally, the tertiary phase aims to reduce the effect of the ongoing injury through treatment and long-term management(2,4).

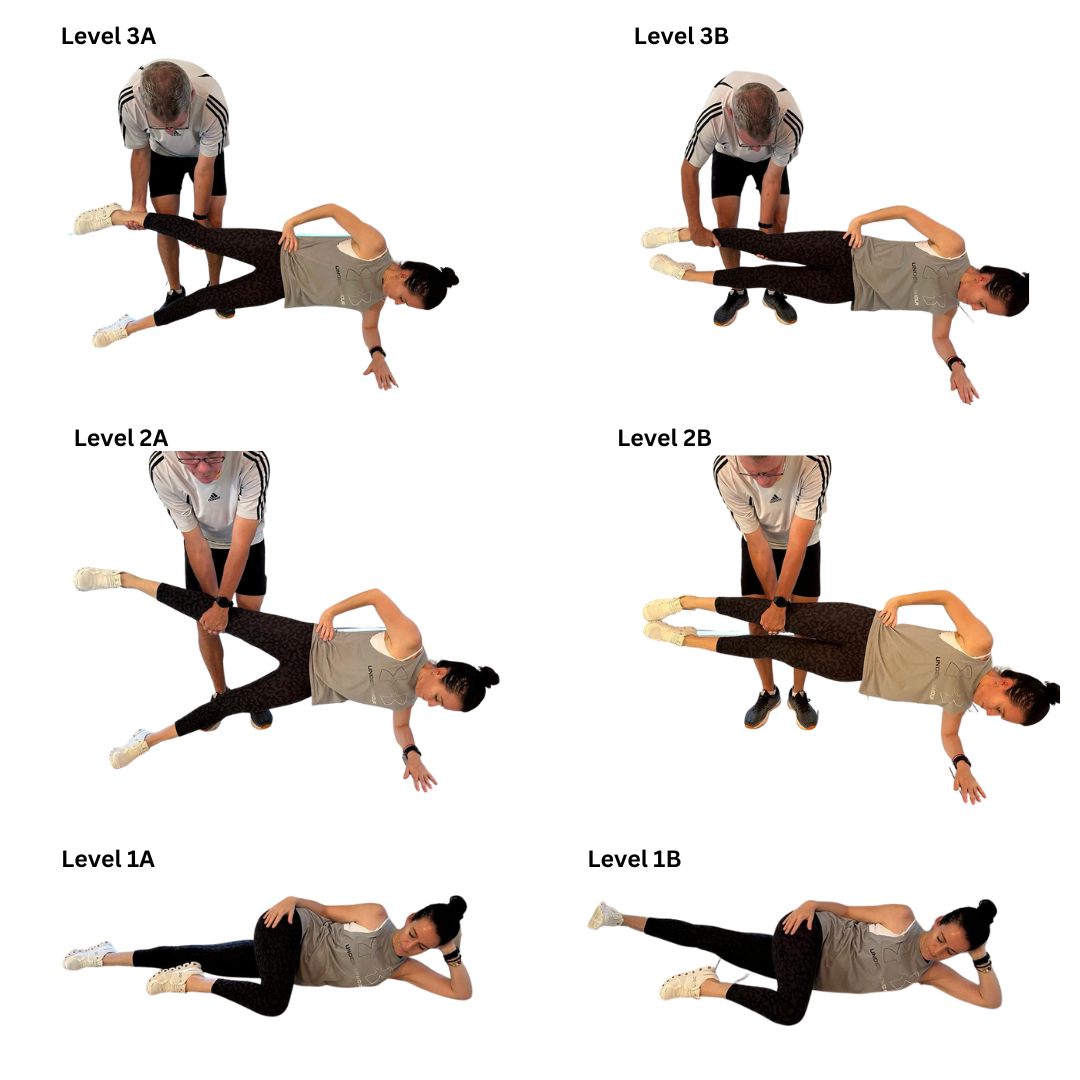

Managing off-season, pre-season, and in-season adductor training load is critical. Programs that include hip, groin, and lumbopelvic muscle strength and coordination exercises are successful. Clinicians must be able to progress or regress programs to meet the athlete’s capacity and injury status. For example, the Copenhagen adductor exercise program is one such program. The success is due to its targeted adductor muscle strength with focused eccentric muscle strengthening (see figure 5)(7).

The success of the secondary prevention phase is early detection(2). Clinicians must regularly screen to identify injury, pain, strength, and performance deficits(8). In this phase, athletes can complete the same exercise program as primary prevention but must select the most appropriate level for their injury severity.

Many players continue to participate despite having groin-related complaints with associated impairments or reduced performance(9). The key to tertiary prevention is to reduce the effect of the ongoing injury by including a comprehensive treatment and rehabilitation program that addresses all the relevant deficits(2). Once again, the Copenhagen adductor exercise progressions offer a pragmatic solution. In long-standing groin pain, clinicians must address global deficiencies that may have developed through ongoing compensatory movement patterns and treat the specific structures that sustain acute overload. Clinicians should follow the fundamental rehabilitation principles:

- Exercise variety,

- Progressive loading,

- Developing endurance capacity by increasing the time under tension,

- Appropriately integrating plyometric-type exercises in preparation for return to sport.

Adductor Injury Rehabilitation

Clinicians must monitor the severity, intensity, and nature (SIN) of the pain throughout rehabilitation, as this is the guiding factor when determining exercise intensity. Using the numeric pain rating scale, athletes can accurately monitor their pain(10). If symptoms seem to be regressing, clinicians and athletes must spend more time assessing the symptoms before progressing the rehabilitation. Furthermore, the soft tissue healing stages guide the rehabilitation phases(11).

The Acute/Subacute Phase

Soft tissue healing and regeneration occur in this phase(11). Therefore, the goals are to protect the injured tissue, control pain, reduce inflammation, normalize tissue length, and prevent muscular inhibition and compensatory patterns. Clinicians can do this by implementing SIN-appropriate exercises(2).

Conditioning Phase

As soft tissue repair and regeneration occur in this phase, clinicians can progressively load the adductors(2,11). They can utilize the exercise continuum (isometric, concentric, and eccentric) to create appropriately challenging hip adductor strength programs. Notably, due to the stabilization functions in weight-bearing and mobilization functions in open chain movements, exercises should always be done bilaterally, thus addressing the adductors as prime mobilizers and stabilizers. Furthermore, clinicians need to include balance and coordination exercises using unstable surfaces and sliding boards and engage upper and lower limb movements to improve the capacity of the entire kinetic chain(2).

Sport-Specific Exercise Phase

Restoring sport-specific local tissue and systemic capacity is vital when preparing athletes for RTS(2). To avoid placing excessive load on the musculotendinous structures, conditioning should continue with isometric, concentric, and eccentric slow and heavy contractions. Introduce one load change at a time, changing the speed of the contraction, then the load (resistance), and remember that these exercises need to be performed through the full range of motion to meet the demands in kicking and skating sports. Moreover, clinicians must include plyometrics.

Return to Sport Phase

When returning athletes to sports, clinicians should expose them to the skills that they require for their sport. This may be done in isolation first and then incorporated with more cognitively demanding tasks(2). As the athlete’s objective (strength and function) and subjective (pain and confidence) improve, the clinician can progress the program. Once they have undergone this graded re-introduction to training and successfully completed field-based tests, they can join the rest of their team, participating in the full weekly training sessions.

Adductor injuries are common problems in athletes. Although they may be isolated, they often involve associated groin symptoms and injuries. Clinicians must continuously assess and monitor athletes through rehabilitation. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical to reducing RTS timeframes. Rehabilitation is successful when clinicians and athletes carefully adjust it in response to symptoms presenting over time. Athletes can return to sport and performance if they comply and consistently use well-designed rehabilitation programs.

References

- Am J Sports Med. 2017; 45(12): 2713 – 2722.

- J Athl Train. 2023. 58 (7/8): 589 – 601.

- Br J Sports Med. 2019; 53 (9) 539 546.

- J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018; 48 (4): 239 249.

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018; 28 (2): 667 - 676.

- Sports Med. 2016; 46 (12): 1847 – 1867.

- Br J Sports Med 2019; 53: 145–152. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098937

- J Sci Med Sport. 2018; 21 (10): 988 – 933.

- Am J Sports Med 2017;45: 1304–8.

- www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/numeric-rating-scale

- Pri Care: Clinics in Office Practice 2020; 47 (1): 87 – 103.

- J Athl Train. 2004; 39(1):24 – 31.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.