You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Uncommon injuries: Pes anserinus part II - the road to recovery

As explained in part one of this article, an injury to the pes anserinus (PA) can cause debilitating knee pain that mimics other injuries. Correctly identifying this comparatively rare diagnosis prevents an athlete from undergoing unnecessary surgery. Most PA injuries in athletes involve high hamstring loading (or a direct contusion) combined with sub-optimal biomechanics – for example, extreme pronation in running gait with excessive rotary stresses applied to the knee(1). Treatment options for PA injuries, therefore, typically involve an element of biomechanical correction such as stretching, strengthening, gait retraining, and the use of corrective orthotics when appropriate.

Treatment pathways

1) Relative rest and modification of training load

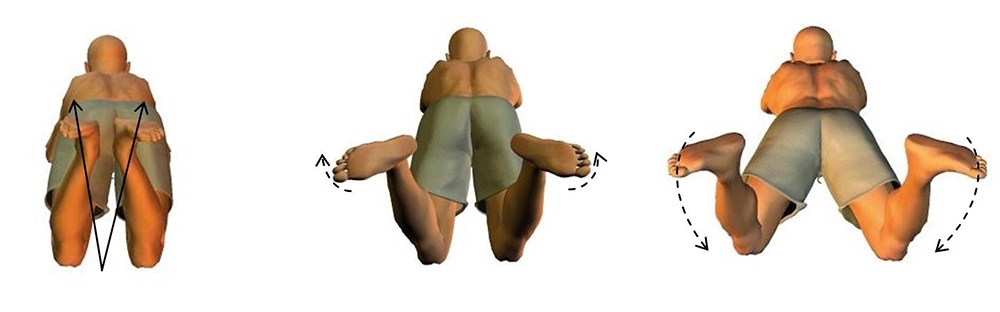

In many athletes, the most-likely offending activity is running; research shows that distance runners are particularly vulnerable to PA injury(2). Other activities that involve significant and repetitive hamstring and PA loading include rowing, speed skating, and breaststroke swimming. Swimmers who use mainly breaststroke are vulnerable because the movement requires hamstring contraction combined with rotation at the knee (see figure 1). In addition to removing offending activities, athletes who sleep on their side may also benefit from using a pillow between the knees at night, which helps alleviate direct pressure on the PA tendons and bursa.

Figure 1: Breaststroke and hamstring/PA loading

Left: heels drawn close to buttocks.

Middle: rotation at the knee as feet turn outwards.

Right: a whip/kicking action produced by knee extension. Following this, knee flexion (hamstring contraction) and internal rotation return feet to the start position.

2) Decreasing inflammation in the PA complex (3).

Treatment strategies to help reduce initial pain and swelling (if present) include regular icing (15-20 minutes every 2-3 hours) and the use of over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medication such as Ibuprofen. In more severe cases, stronger NSAIDs such as Naproxen may be prescribed. Another early-intervention treatment strategy that may be useful is kinesiotaping. In a study examining treatment protocols for PA tendino-bursitis, the effects of kinesiotaping were compared with the use of NSAID drugs (Naproxen) combined with physical therapy(4). In a 10-day trial, 56 patients were randomized to one of two groups:

- A kinesiotape group – where a space-correction lifting technique was used on the tender area (to reduce pressure on the PA bursa) and reapplied three times over the 10 days.

- A Naproxen (250mgs per day) plus physical therapy group.

The results after 10 days showed that in comparison with naproxen and physical therapy, treatment with kinesiotaping significantly decreased the pain and swelling scores (after adjustment for baseline characteristics). Moreover, the kinesiotaping proved safe, without any complications except for mild local skin irritation in one patient. This may be an important consideration in athletes who are sensitive to NSAID medication – eg experience heartburn and gastric discomfort.

3) Biomechanical assessment and rehabilitation

In most cases, the discomfort of a PA injury and accompanying swelling subside within 2-3 weeks. After this initial period, begin appropriate stretching and strengthening exercises. The length of this rehab period varies but expect from three to eight weeks of physiotherapy before the athlete can return to play(5).

As mentioned in part one of this article, excessive valgus forces – eg as a result of excessive pronation in the running gait or a faulty breaststroke technique –significantly increase loading on the PA complex(6). A biomechanical analysis should include careful observation of the runner’s gait (or swim stroke) and an inspection of their shoes to determine foot strike and stance patterns. When excessive pronation is present, recommend motion control shoes with the addition of orthotic inserts where necessary. A knee brace with lateral stays can serve as a reminder to limit valgus motion during the gait retraining process. However, bracing is notrecommended as a treatment strategy for PA injuries.

Recommended program

In the early stages of a PA injury rehab, begin with stretching the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles. Both passive and active stretching promotes a significant reduction in the tension experienced by the anserine bursa. One example of a hamstring and adductor stretch is the ‘butterfly’ stretch, also known as the seated adductor stretch (see figure 2). Stretch the calf and quadriceps muscles also to relieve tension on the joint further.Figure 2: Butterfly stretch to reduce tension in the PA complex

Place heels together and apply gentle downward pressure by the elbows to increase the stretch.

During the first week of rehab, begin gentle exercises. These include:

- Simple range of motion exercises for hamstrings, achieved by lying on the floor and sliding the foot up and down the wall.

- Isometric quadriceps contractions in supine.

- Isometric hamstring contractions while in supine with knees bent at 90 degrees and pushing heels into the floor.

Assuming the athlete is pain-free, introduce more dynamic exercises at week three. These include:

- Pistol squats onto a bench or chair – limiting downwards range of motion limited.

- Plié half squats (with toes pointing outward at 45 degrees).

- Split squats or low-range lunges (see figure 3).

- Resistance band exercises in standing with a straight leg - include forward/backward (hip extension/flexion) and medial/lateral movements. Progress these exercises by having the athlete stand with his/her unaffected leg placed on an uneven surface such as a wobble board.

Figure 3: Begin lunges and progress to split squats holding weights

Pain-free progression through the above allows the athlete to move on to more challenging dynamic movements. A suggested sequence is as follows:

- Step-ups onto a low platform (12 inches) – begin with simple step-ups, and then step-downs on the other side of the platform followed by the reverse (step up in a backward motion then step down).

- Resisted perturbation in half-kneeling position – the athlete assumes the half kneeling position with the foot of the affected leg on the floor and the knee at right angles (see figure 4). The clinician applies random lateral and backward/forward forces during which the athlete attempts to remain firmly in position.

- Lateral slides using a slide board.

- Single-leg BOSU ball balances.

- Short arc quads in supine while squeezing a small Swiss ball or volleyball between the knees.

- Swiss ball VMO wall squats, also while stabilizing a small ball between the knees.

- Single-leg (affected side) ball throwing and catching – testing dynamic balance and challenging the stabilizing muscles around the hip and knee.

Once the athlete progresses through these stages without pain, introduce low-level sport-specific training, correcting any further biomechanical imbalances as needed.

Figure 4: Resisted perturbation in a half-kneeling position

The athlete resists random, and sudden perturbation forces applied (arrowed) by a clinician, attempting to remain stationary.

Injection treatments

In the large majority of cases, the conservative treatment options fully resolve PA injuries in athletes. In the more severe or chronic cases of PA injury, however, one may consider interventional treatment methods. One possible route is the use of injection therapy. Although there is a paucity of data in the literature, evidence suggests that the use of platelet-rich plasma injections(7)and polydeoxyribonucleotide injections(8)both produce short-term pain relief and longer-term improvements (over three to six months) in patients suffering from chronic PA syndrome.When considering injection therapy, the specific injection site appears to be important, especially in cases where the cause of the pain is an irritation of the anserine bursa. A cadaveric study concluded that the anserine bursa follows the lines of the sartorius muscle, and is located posteriorly and superiorly to the tibia's midline, beneath the PA tendons(9). Evidence also suggests that unguided PA bursa injections rarely place the injectate within the PA. Ultrasound guidance increases the accuracy of the injection(10).

Finally, surgery on the PA bursa is only rarely required. When conservative measures fail, there’s evidence that debridement under arthroscopy may be superior to open surgery. In a study comparing the clinical outcomes of three therapies in 90 patients with chronic PA bursitis - local block therapy, open operation, and debridement under arthroscopy – the latter proved superior to other treatments. The arthroscopy was easier to execute, and demonstrated fewer complications, a lower relapse rate, and good functional rehabilitation outcomes(11).

References

- Donoghue DH. Injuries of the knee. In: O Donoghue DH, ed. Treatment of injuries to athletes, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1987: 470–471

- Orthop Clin North Am 1995; 26:547–549

- Rev Bras Reumatol. 2010 May-Jun;50(3):313-27

- Phys Sportsmed. 2016 Sep;44(3):252-6

- The Lower Limb Tendinopathies: Etiology, Biology and Treatment edited by Giannicola Bisciotti, Piero Volpi doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33234-5

- J Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Apr;13(2):63-5

- Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2014 May-Jun;16(3):307-18

- Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Oct;96(43):e8330

- Anat Cell Biol. 2014 Jun;47(2):127-31

- PM R. 2010 Aug;2(8):732-9.

- Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009 Sep;23(9):1045-8

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.