You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Uncommon injuries: Pectoralis major ruptures part I

In the first of a two-part series, Chris Mallac explains the functional anatomy of the pectoralis major and its tendon, the situations that place the tendon at risk for injury, and the signs and symptoms of a ruptured tendon.

The first reported case of pectoralis major (PM) tendon rupture occured in Paris in 1822. Up until 2010, only 365 cases were documented in the literature(1). However, three-quarters of them occurred within the last 10 years of the review, signifying a significant uptick in the occurrence of this injury. Despite the evolution of sports and increased sports participation since the 1800s, this injury remains rather rare(2).

Pectoralis major tendon ruptures tend to occur in athletes aged 20 to 40 years-old. It afflicts males much more than females. In fact, the first report of a female under 40 years old suffering a PM rupture didn’t appear in the literature until 2019(1).

Anatomy and Biomechanics

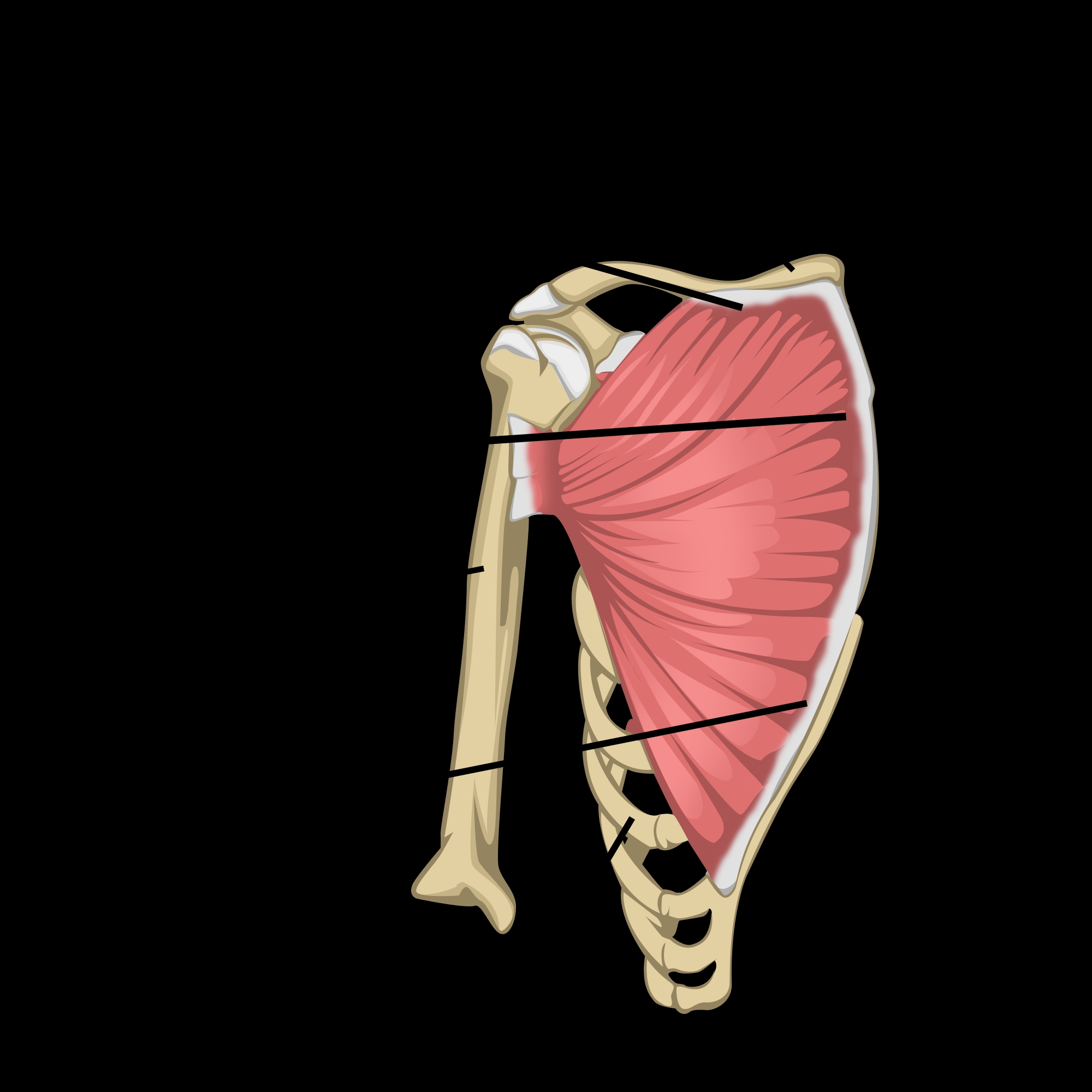

The PM muscle has two distinct heads, the clavicular head, and the sternocostal head (see figure 1). The clavicular head originates on the medial clavicle and upper sternum. The sternocostal portion of the muscle begins on the sternum, the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle, and the costal cartilage of the first six ribs. They both converge laterally to form the anterior wall and fold of the axilla and extend across the shoulder to insert onto the proximal humerus(3).

The insertion of the tendon has two key parts. The clavicular and upper sternal portion of the muscle inserts on the humerus distally. This placement positions it below the insertion of the lower sternal and external oblique fibers. The two distinct tendon portions effectively ‘twist’ on each other 90º-180° before their insertion on the humerus(4,5). The tendon’s footprint is located approximately 4cm distal to the greater tuberosity on the lateral portion of the bicipital groove. It measures from proximal to distal approximately 70mm and 1.4mm medial to lateral(6).

Figure 1: Anatomy of the pectoralis major muscle

Note the upper clavicular portion of the muscle and its insertion on the distal portion of the bicipital groove. The lower sternocostal fibers insert more proximally, effectively twisting underneath the upper segment.

Knowing the insertions’ placement is essential to understanding the muscle’s function and the mechanism of injury. The sternocostal portion’s tendon, located more proximally on the humerus, lengthens disproportionately in the final 30° of humeral extension compared with the clavicular segment(7). Thus, this part of the muscle has a mechanical disadvantage in the final eccentric phase of a maneuver, such as a bench press, making these inferior sternocostal fibers more prone to injury and rupture. This disadvantage means partial ruptures of the tendon (isolated to the sternocostal portion) occur more frequently than complete tears of both heads.

The PM functions as a powerful shoulder internal rotator, adductor, and flexor and plays a role in the shoulder girdle’s overall stability. However, it is not necessarily employed strongly for everyday tasks, as the other shoulder muscles produce the required force for activities of daily living(8). It is essential for many sports, suggesting that athletes may require surgical repair in the event of a rupture, while the sedentary and elderly may do well with conservative management.

Mechanism of Injury

Injury to the PM is usually caused by a sudden forceful overload while maximally stretched (such as the eccentric portion of the bench press) or forceful direct contact when in an elongated position (such as a rugby tackle). Overloading while stretched damages the insertion and musculotendinous junction, whereas direct blows typically injure the muscle belly.

The types of injuries that occur to the PM include contusion, strain, partial or complete muscle tear, muscle origin tear, musculotendinous junction (MTJ) or tendon tear(9). Complete rupture of both heads rare. Typically, only the inferior fibers of the sternocostal head rupture, which may give a false impression that the entire tendon is still intact. Complete tears almost always include an avulsion of the outer lining of the humerus.

Typical mechanisms of injury include:

- Tackling in contact sports such as rugby and American football.

- Bench pressing, particularly at the bottom of the lift, if the weight is suddenly bounced off the chest or if the lifter arches the spine to avoid ‘going over’.

- Water skiing or windsurfing if the arm is externally rotated and extended, and a sudden stretch is applied due to a fall, gust, or jolt.

- Wrestling if the arm is caught in an awkward position.

Some believe that a healthy tendon is immune to rupture and that a focus of degeneration must be present for the tendon to fail(10). Repetitive weight training may subject the tendon to chronic stressful loads that lead to tendon degeneration. Furthermore, bodybuilders in cycles of high anabolic steroid use are more prone to this injury due to the tendon stiffness associated with steroids(11).

Signs and Symptoms

Patients usually complain of a sudden sharp pain in the upper chest over the shoulder, often associated with a ‘ripping’ or ‘popping’ sensation. The sufferer will guard the shoulder and complain of pain upon movement in the days following the injury. Bruising may develop in the axilla and upper bicep area.

Other types of injuries can cause similar symptoms. In a study conducted in New Zealand, researchers found that 50% of subjects with PM tears were initially misdiagnosed in the acute setting(12). Therefore, understanding the presenting signs and symptoms is crucial for medical personnel dealing with acute soft tissue trauma in athletes. A delay in surgical repair due to a misdiagnosis may lead to poorer functional outcomes(12).

Physical examination reveals a thin axillary fold or sulcus where the deltoid and pectoral muscle cross. Active contraction of the muscle shows a proximal bulging in the anterior chest wall. To elicit this contraction, ask the patient to press their hands together forcefully in a prayer position. A definitive defect will often be present in the anterior chest wall in front of the shoulder(3,11).

Initially, pain limits the range of shoulder movement into abduction and external. However, this may not last more than a few days. While the athlete may regain their range of motion, they will demonstrate weakness moving in internal rotation with shoulder flexion.

Imaging

Plain X-ray usually proves inconclusive. However, the absence of a pectoral shadow may suggest a rupture of the pectoral tendon. Ultrasound may visualize the tear and show the thinning of the muscle with variable echogenicity. CT scans may show disruption of the muscle tendon.

MRI is the most accurate imaging modality, with axial T2 weighted images being the most useful MRI sequence for acute injuries and T1 weighted images the best for chronic injuries. MRI will also show muscle belly hematoma and can be used to confirm patients who will benefit from surgical treatment(3,11).

Conclusion

Ruptures of the PM tendon are reasonably rare. They typically occur in males between 20 and 40 years old. The mechanism of injury is usually weight-lifting, a contact sport situation, or aggressive overstretch. A level of underlying degeneration may be present, especially if the patient uses anabolic steroids. The injury is usually associated with acute pain and audible popping sensation. An MRI is the best modality to confirm this injury. Part II of this series focuses on the management and rehabilitation of PM ruptures.

References

- JAAOS: Global Research and Reviews. 2019 Oct;3(10):p e19.00030

- Arthroscopy Techniques. 2012; 1(1): e119-e125

- Br J Sports Med. 2002; 36: 226–228

- Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2012; 2(2); 96-103

- Am J of Sports Med. 2010; 38(8): 1693-1705

- 2010; 33:23

- Am J of Sports Medicine. 1992; 20; 587-593

- J Bone and Joint Surgery (A): 1961: 43; 81-87

- J Trauma. 1980; 20; 262-264

- J of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1991; 73(10; 1507-2573A

- Asian J Sports Med. 2014; 5(2); 129-135

- Br J of Sp Medicine. 2001; 35: 201-206

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.