You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Uncommon injuries: Kim lesions

Glenoid labrum injuries are common shoulder injuries in athletes and research shows that among these, posterior labral lesions form a significant proportion(1). The posterior labrum is particulary vulnerable in sports such as contact football players (NFL, rugby), climbing sports, weight lifters and paddling sports(2), and is also found in the hypermobile lax shoulders.

Posterior labral injuries

Injuries to the posterior labrum usually occur due to loading of the labrum with the arm in flexion and internal rotation. In this position (similar to the blocking position of the football lineman and the powerlifter at the top of a bench press) the most significant shoulder stabiliser is the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. The ligament and the attachment to the posterior labrum, are placed under tension in an anterior-posterior orientation(3). In addition, the posterior labrum increases the concavity-compression mechanism of the humeral head. In cases of recurrent posterior instability, it is common to find chondrolabral retroversion or glenoid retroversion, and a loss of height of the posteroinferior labrum(4).Injuries to the posterior labrum can occur in the posterior aspect of the labrum from the 7-10 o’clock position (right shoulder), while inferior lesions occur from 5-7 o’clock positions. Injuries to the posterior labrum are varied. Some common examples are:

- Detachment of the labrum (Reverse Bankart lesions). These posterior detachments are often undisplaced compared with anterior Bankart lesions, which often do displace away from the glenoid(5)

- Bucket handle lesions

- Flap tears

- Labral splits

- Chondrolabral erosion

- Kim’s Lesions

Kim et al (2004) simplifies the grading of posterior labral tears into four subgroups(5):

- Type 1: Incomplete detachment. The labrum (posteroinferior portion) is detached from the glenoid margin but not displaced.

- Type 2: Kim Lesion (see below).

- Type 3: Chondrolabral erosion.

- Type 4: Flap tear of the labrum.

The ‘Kim lesion’

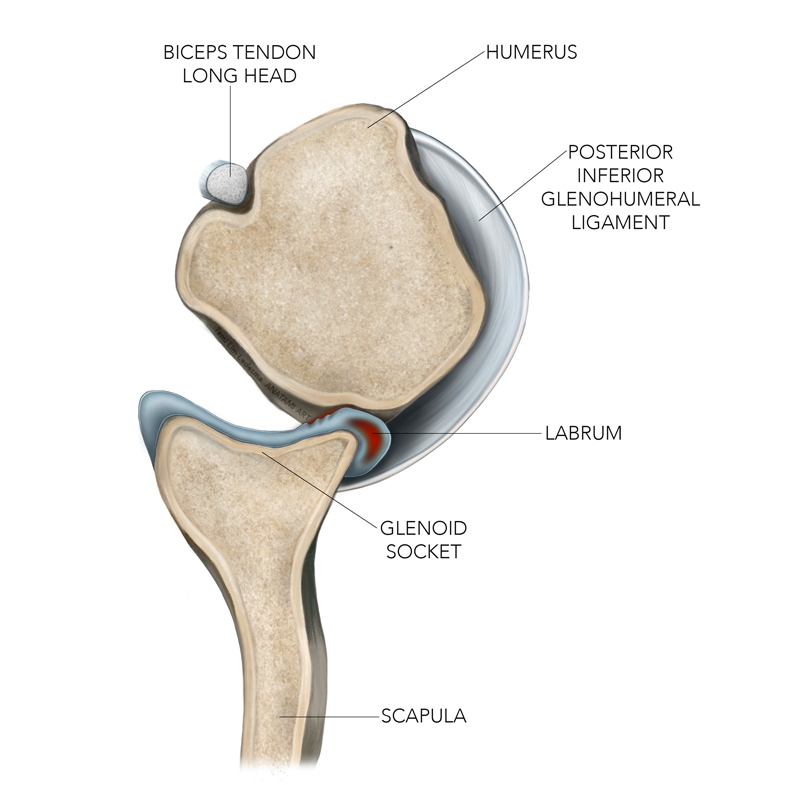

The Kim lesion is a unique posterior labral injury that is described as a ‘marginal crack’ in the deep posterior labrum, which is concealed by an intact superficial labrum(1). In essence it is a superficial tear between the glenoid articular cartilage and the posterior and inferior part of the labrum (see figure 1 for an overview of the anatomy). The posteroinferior labrum loses its natural height and flattens out and the chondrolabral glenoid retroverts. These are usually only present in the 6-9 o’clock positions of the glenoid (right shoulder).It is suggested that the Kim lesion may be caused by repetitive sub-maximal posterior force on the glenohumeral joint. A posterior force will initially focus its stress onto the inferior labral attachment (rim loading theory)(1). It is in this area that the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament attaches. If the amount of force is small, only the inner portion of the labrum is affected. The chondrolabral junction is not affected. At this point in the pathology, the shoulder may be loose and may reproduce a clunk on testing (see below), although pain is not usually felt.

Figure 1: Anatomy of relevant structures involved in a Kim lesion

The resultant loose deep portion of the labrum may lead to a shear force developing across the chondrolabral junction under conditions of repetitive posterior stress. This can eventually create a marginal crack in the chondrolabral junction, which may finally progress to tear the entire chondrolabral surface. At this point in the process, the shoulder will reproduce a painful clunk on testing (see below).

Interestingly, some authors have suggested that an injury to the posteriorinferior labrum (such as a Kim Lesion) in the presence of anterior unidirectional instability may lead to the phenomenon known as multidirectional instability. If labral damage extends both anteriorly and posteriorly, the instability will exist in multiple directions(6).

Signs and symptoms

The patient who typically complains of a Kim lesion may notice a deep and vague posterior shoulder pain that is exacerbated by carrying heavy objects (due to the traction effect of the humeral head being depressed and abutting the posteriorinferior labrum). This may occur in heavy carrying movements such as deadlifts and Olympic weightlifting. The pain may also be associated with an audible click or clunk.This can be assessed through a sulcus sign whereby passive downward traction is applied to the shoulder and the amount of translation between the humeral head and inferior acromian is assessed. No movement is graded as a 0, grade 1 is less than a centimetre, grade 2 is 1-2 cms, while a grade 3 is more than 2 cms(7).

A number of tests exist to diagnose a posterior labral injury. These include the Kim test, the 'jerk' test, and the Porcellini test. The sensitivity of the Kim test (see figures 2 and 3) for posterior labral tears is 80% and the specificity is 94%, with a positive predictive value of 0.73 and a negative predictive value of 0.96(8). When combined with a ‘jerk’ test (see figures 4 and 5), two positive findings of pain leads to 97% sensitivity for a posterior labral injury(8).

The Kim Test can be considered as a specific test for posteroinferior labral lesions. The key feature is pain in the posterior shoulder. A pain without a sensation of a clunk is more suggestive of a simple labral lesion, however a test that produces both pain and a clunk suggest a labral lesion with a component of instability(8,9).

A more recent test for the diagnosis of posterior labral lesions is the Porcellini test (see figures 6 and 7), providing 100% sensitivity, 99.3% specificity, positive predictive values of 92.6% and negative predictive value of 100%. This effectively means that if the patient has posterior labral tear then this test will be positive. Conversely, if the test is negative then it is unlikely the patient has a posterior labral injury.

Figures 2 and 3: The Kim test

- Sit the patient on a high backed chair (back needs to be supported) and stand next to the affected shoulder.

- Abduct the arm to 90 degrees.

- To test the left shoulder, hold the elbow of the patient with the left hand and the upper arm with the right hand.

- Apply a posteriorly-directed axial load through the elbow with the left hand.

- Elevate the arm 45 degrees upwards and maintain the left handed axial load and apply a posterior force on the upper arm with the right hand.

- The test is positive if a pain in the back of the shoulder is felt with or without a clunk.

| Figure 2: Kim test start position | Figure 3: Kim test finish position |

|---|---|

|  |

Figures 4 and 5: The 'jerk' test

- In the same sitting position as described in the Kim test, hold the patient’s left elbow with the left hand, with the arm in 90 degrees flexion and internal rotation.

- Stand behind the patient to stabilize the scapula with the right hand.

- Apply an axial compression to the elbow to load the posterior part of the labrum with the humeral head.

- Horizontally adduct the patient’s arm with the axial load maintained on the posterior shoulder.

- A positive test is if pain and/or a clunk is felt in the posterior shoulder. It is possible for a second clunk to be felt when the arm is returned to the starting position.

| Figure 4: Jerk test start position | Figure 5: Jerk test finish position |

|---|---|

|  |

Figures 6 and 7: The Porcellini test(10)

- The patient stands or sits with the arm raised to 90 degrees flexion.

- Stand behind the patient and adduct the arm horizontally 10-15 degrees while internally rotating it.

- Apply a downward pressure to the arm and note the patient’s symptoms. They usually experience pain inside the shoulder or pain at the acromioclavicular joint.

- Apply an anterior force on the humeral head using their thumb of the hand that is stabilizing the scapula.

- If the pain is diminished or absent then this represents a positive test.

| Figure 6: Porcellini test start position | Figure 7: Porcellini test finish position |

|---|---|

|  |

Treatment

Initial treatment will usually consist of conservative management, which includes a graduated and physiotherapy-led strength program for the scapular stabilisers and rotator cuff. In 80% of patients with atraumatic instability, rehabilitation works well to resolve their symptoms(11). Kim et al (2004)⁵suggest that conservative rehabilitation works well in the young hyperlax female who develops symptoms spontaneously.In the event of failed conservative rehabilitation over a minimum six month period, surgical stabilisation will be necessary to restore the shoulder to a pain-free and functional state. It is beyond the scope of this paper to describe in detail these arthroscopic procedures. However the reader is directed to the following references for further information(¹²).

Post-operative rehabilitation

Following surgery for a posterior labral injury, the clinician needs to follow the following guidelines to steer the patient’s rehabilitation:- Sling immobilised for three weeks with a pillow spacer to allow 30 degrees abduction and neutral rotation.

- The arm is kept posterior to the body to prevent the repaired tissue from being stretched.

- Isometric exercises are performed in this position.

- From three weeks onwards, the patient may commence pendulum exercises, active assisted range of motion exercises (forward flexion and external rotation).

- From four weeks, hand behind back internal rotation is allowed to be active assisted.

- Internal rotation in a cross body position is prohibited until week six.

- Strength exercises begin from week six.

- Return to full competition is usually at 4-6 months depending on strength testing parameters.

References

- 2004;20:712-720

- The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011; 39(4): 874-886

- J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(3):433-440

- J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:92-98

- Oper Tech Sports Med. 2004;12. 111-121

- British Elbow and Shoulder Society. Shoulder &Elbow 2010, pp71–76

- Orthop Clinics of North America. 1977; 8; 583-591

- The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005; 33(8), 1188-1192

- Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1849-1855

- Musculoskelet Surg (2016) 100: 199–205

- J Bone and Joint Surgery America. 1992; 74; 890-896

- Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:594-607

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.