You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Uncommon injuries: ischio-femoral impingement

Athletes often complain about pain in the posterior hip that sometimes radiates down the back of the thigh. Causes for this include well-known pathologies such as lumbosacral radiculopathy, sciatica, snapping iliopsoas tendon, piriformis syndrome, hamstring tendinopathy, hip joint labral injury, ischial bursitis, and spinal stenosis. The more rare IFI is caused by abnormal contact between the lesser trochanter and the lateral border of the ischium, due to extremes of hip extension, adduction and external rotation, in athletes who may possess particular structural anatomical faults(1-3). Athletic populations prone to IFI include runners with long stride lengths, race walkers, ballet dancers and rowers (who force themselves into hip extension at the end of their stroke phase).

Patho-anatomy

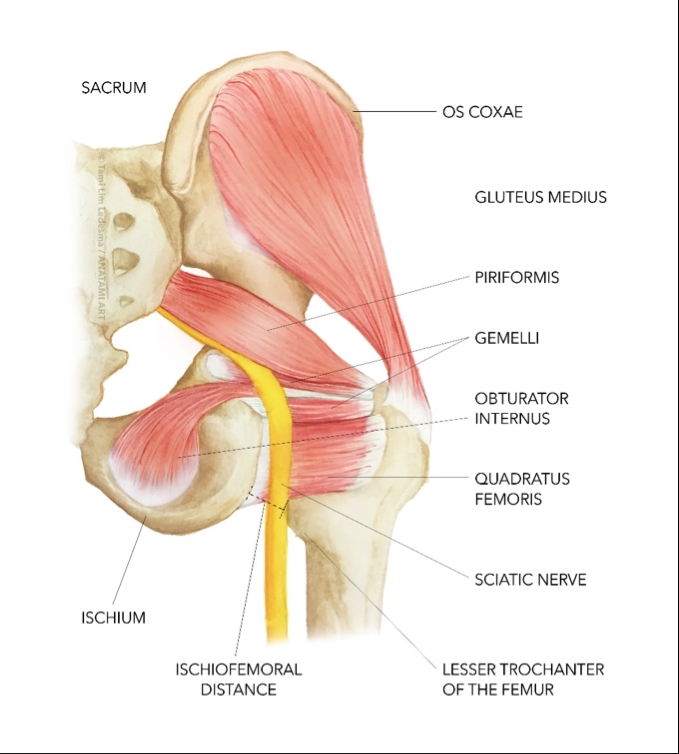

Johnson first documented IFI in 1977, when he noticed that some patients (non-athletes) had persistent pain in the medial thigh and groin following total hip arthroplasty(4). These patients noticed temporary relief following an injection of anaesthetic near the lesser trochanter. This prompted the idea that the lesser trochanter and ischium may in fact impinge during particular surgical procedures such as total hip replacement. Long-term relief was achieved by excision of the lesser trochanter. However, IFI was not well described in the non-surgical patient until 2008(5,6).Impingement between these structures is uncommon as the normal distance between the lesser trochanter and ischium (the ischiofemoral distance) is approximately 20mm in hip extension, adduction and external rotation (see figure 1)(4-6). This allows the femur to rotate without impingement of the ischial tuberosity or proximal hamstring tendon(6). A study at Harvard Medical School found the ischiofemoral distance significantly reduced in subjects with IFI when compared with control subjects(6). This suggests that structural abnormalities play a role in the development of this syndrome.

With a narrow ischiofemoral distance, the lesser trochanter may bump against the ischium and squash the intervening soft tissues. This may lead to oedema or tearing of the quadratus femoris muscle or the hamstring tendon. Consider IFI in patients complaining of hip pain with snapping. Delayed diagnosis of IFI can lead to a bursa-like formation surrounding the lesser trochanter or fatty infiltration in the quadratus femoris(6).

Figure 1: Posterior hip showing the ischiofemoral distance

The quadratus femoris muscle externally rotates and adducts the hip. It originates at the inferolateral margin of the ischium along the anterior portion of the ischial tuberosity, just anterior to the origin of the hamstrings, and inserts at the quadrate tubercle of the posterior intertrochanteric ridge of the posterior medial femur. Its anatomical position leaves it vulnerable to impingement between the lesser trochanter and the ischium.

Acquired, positional and congenital factors in IFI

Particular acquired movement (positional) and congenital faults can narrow the ‘ischiofemoral’ space and predispose the femur to impinge against the ischium(7).Acquired causes include(4):

- Intertrochanteric fractures with involvement of the lesser trochanter.

- Valgus producing intertrochanteric osteotomy.

- Reduced horizontal offset in hip arthroplasty.

- Osteoarthritis, leading to superior and medial migration of the femur.

Positional faults include:

- Movements that increase the extension, adduction and external rotation movements at the hip – for example ballet and fast walking may do this.

- Poor hip/pelvis control due to gluteal weakness

Congenital faults include:

- Femoral neck anteversion. This is significantly higher in patients with symptomatic IFI compared to asymptomatic hips(8).

- Valgus femoral neck(6).

- Increased femoral diameter at the lesser trochanter(6).

- Posteromedial femoral position(6).

- Female morphology of a broad shallow pelvis(6).

Signs and symptoms

Pain felt deep to the posterior hip, often accompanied by a ‘snapping hip’ may indicate IFI. Irritation of the sciatic nerve by a swollen quadratus femoris muscle may cause additional pain along the posterior thigh. The major symptoms in patients with IFI are as follows(9):- Deep lower-buttock pain.

- Anterior groin pain, which radiates posteriorly around the inner thigh to the lower buttock area.

- Tenderness to palpation of the ischiofemoral space (see box 1).

- Discomfort in sitting on the ischial tuberosity for extended periods.

- Either a positive IFI testor a positive long-stride walking test (see box 1)(10).

- Pain relieved by injection into the ischiofemoral space (see box 1)(11).

Box 1: Diagnostic tests

Ischiofemoral space tendernessThis is elicited by putting the patient in the prone or seated position and palpating the area just lateral to the ischial tuberosity. Patients with IFI will have marked tenderness with pressure applied lateral to the ischium over the ischiofemoral space, and the location of their pain lateral to the ischium is important in the diagnosis of IFI(9).

The IFI test

First described by Hatem et al who noted that the symptoms of IFI could be reproduced by a combination of extension, adduction and external rotation of the hip(10). This test can be performed with patients in the lateral decubitus position, and the contralateral hip down on the table. The affected hip is then extended and adducted. The test is considered positive if the patients symptoms are reproduced when the hip is put in an extended and adducted position.

Long-stride walking test

Ask the patient to walk taking long, exaggerated strides. The test is considered positive if their long strides reproduced their posterior buttock pain, and walking with short strides alleviated their pain(10).

Diagnostic block

Diagnosis of IFI is often delayed because the patient’s history (anterior and posterior hip pain, deep snapping sensation) and limited clinical findings are not definitive. In patients with groin and buttock pain and MRI findings of IFI, ultrasound-guided anaesthetic injections of the quadratus femoris muscle and ischiofemoral space will confirm that IFI is the cause of the patient’s hip pain(11).

Imaging

MRI of the hip may show an increased signal intensity of the quadratus femoris muscle and abnormal narrowing of the ischiofemoral and quadratus femoris space(6,12). There has been debate in the radiology literature as to the cause of the abnormally high signal returned on MRI, which has been attributed either to impingement or to a quadratus femoris tear. In the presence of IFI, good quality axial T2-weighted images will show oedema within the muscle belly of quadratus femoris without disruption of its fibres(13). Sclerosis of the lesser trochanter may also be seen on MRI, again suggesting a chronic condition rather than an acute injury(13). Coronal sections may also show oedema between the lesser trochanter and the ischial tuberosity.In an MRI study, Khodair et al found quadratus femoris muscle abnormalities indicative of IFI type pathology(14). Eight patients (57.1%) showed diffuse muscle oedema, three (21.4%) focal oedema, two (14.3%) partial tears, and one (7.2%) diffuse muscle atrophy. Associated partial tear of the hamstring tendon was found in one IFI syndrome patient (7.2%). No marrow oedema or cystic changes were noted in the ischial tuberosity or lesser trochanter of any of IFI syndrome patients in this study.

Treatment

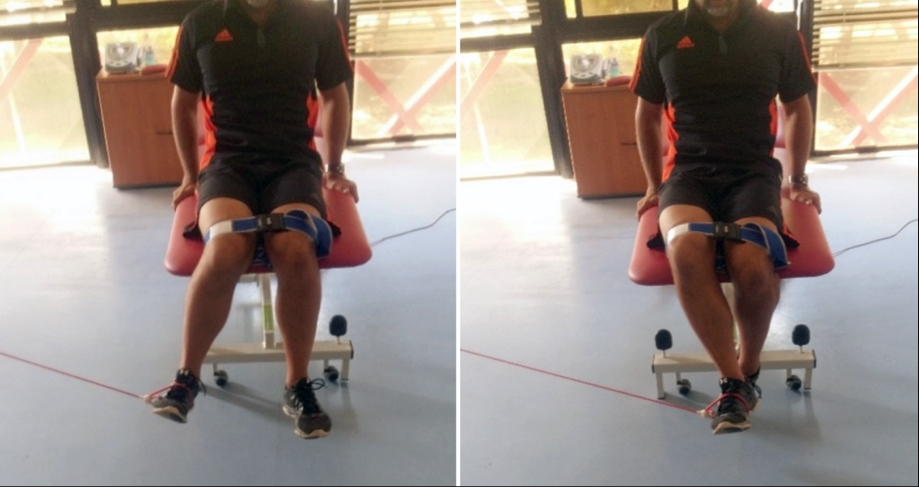

*Conservative treatmentA treatment approach that includes strengthening gluteal muscles helps control the pelvis and lower limbs when moving into extension, adduction and external rotation. Due to the associated quadratus femoris atrophy with IFI, strengthening the deep hip rotators may be beneficial. Strengthening may also desensitise the quadratus femoris through graded exposure. Exercises such as seated hip external rotation can help. Perform in sitting and strap the knees together with a luggage belt. Place a resistance band around the ankle to progressively resist external rotation (see figure 2).

Except when specifically working the external rotators, exercise athletes in positions that do not compress the quadratus femoris. Bridging and clamshell exercises strengthen the pelvic musculature while avoiding combined extension, adduction, and external rotation. To increase comfort, suggest athletes limit prolonged sitting and sleep in side lying with a large pillow between the legs, keeping the hip slightly abducted and in neutral rotation.

Figure 2: Seated hip External Rotation

*Surgical treatment

Surgical management of IFI is poorly understood and to date there are only a few reports regarding diagnosis and treatment of this problem(4-7,13,15-17). Surgical treatment for athletes and active individuals whose pain and snapping are not relieved by activity modification and ischiofemoral space injections has not been clearly defined(10,18-20)but Johnson initially described open excision of the lesser trochanter to manage this problem(4). To date however, there are only five published reports regarding the arthroscopic treatment of IFI(9,10,18-20).

The common feature of arthroscopic surgical interventions is that the lesser trochanter is excised or partially excised, thus removing the anatomical abnormality: This can be achieved by:

- Successful endoscopic release of her iliopsoas tendon and a resection of the lesser trochanter through an anterior approach(18).

- Endoscopic resection (partial) of the lesser trochanter through two anterolateral portals established at the level of the lesser trochanter(19).

- A posterolateral approach for decompression of the ischiofemoral space using a ‘cutting block’ technique to partially resect the lesser trochanter for decompression of the ischiofemoral space. This technique is minimally invasive and preserves the attachment of the lesser trochanter(20).

- The largest case series reported to date was that of Hatem et al(10). They reported the 2-year results of five patients with IFI who underwent endoscopic partial resections of their lesser trochanter through a posterior approach, which they accessed by resecting and creating a small window in the quadratus femoris muscle at the level of the lesser trochanter. The posterior one-third of the lesser trochanter was resected.

- Wilson and Keene evaluated the clinical results of seven patients with IFI where arthroscopic iliopsoas tenotomies were performed in conjunction with resection of the lesser trochanter through an anterior approach(9). Hip scores and functional improvement after one year were significant, and none of the patients had recurrent snapping of their tendon, hip flexor weakness or heterotopic bone formation.

Conclusion

IFI is a rare condition, which may mimic other syndromes by producing posterior hip and thigh pain in the athlete. This rare condition more often occurs in athletes who need to extend, adduct and externally rotate the hip such as ballet dancers, sprinters, race walkers and rowers. Further research is needed to improve both diagnosis and treatment, particularly the role of physical therapy in its conservative management.References

- AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16:1605-13

- Muscle Nerve 2009;40:10-8

- Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:253-65

- J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:268-9

- Skeletal Radiol 2008;37:939-41

- AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:18690

- Skeletal Radiol 2011;40:653-6

- 2016. 32(1): 13-8

- Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2016. 3(2), 146–153

- Arthroscopy 2015; 31:239–46

- AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 203: 589–93

- Ann Rehabil Med 2013;37(1):143-146

- AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;190:W379

- Eg J Radiol Nuclear Med. 2014;45(3):819–24

- Skelet Radiol 2012; 41: 575–87

- J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 2: 2–6

- Hip Int. 2013; 23: 35–41

- Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22: 781–5

- Journal pf Hip Preservation Surgery. 2015; 2: 184–9

- Arthrosc Tech 2014; 3: e661–5

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.