You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Triumphs Over Rehabilitation Thinking Traps

Injured athletes navigating the rehabilitation journey grapple with complex emotions and negative thought patterns. Dr. Carl Bescoby sheds light on common thinking traps that can hinder recovery. He explores strategies for clinicians to empower athletes to overcome these cognitive distortions to optimize their recovery process.

Asian Games - Hangzhou 2022 - Judo - Japan’s Shiho Tanaka in action with North Korean’s Songhui Mun during the Women’s 70Kg Final - Gold Medal Contest REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon.

Introduction

Clinicians and athletes may underestimate the psychological toll of sports injuries. When athletes are sidelined due to injury, they grapple with physical pain and a complex range of emotions(1,2). The abrupt disruption of training routines, competition schedules, and identity can give rise to anxiety, depression, frustration, and self-doubt(3). This is where recognizing and addressing thinking traps becomes apparent(1). Thinking traps, or cognitive distortions, are patterns of thought that lead individuals to perceive reality inaccurately, often magnifying the negative aspects of their situation(4). In the context of injured athletes, thinking traps can exacerbate the already challenging recovery journey.

Negative thinking can hinder motivation, disrupt goals, and erode an athlete’s belief in their ability to bounce back(5). Within this article, we will navigate the mental landscape of injured athletes in recognizing and addressing thinking traps. Clinicians can play a role in understanding typical thinking traps that injured athletes engage in. In doing so, they can help raise awareness and educate them on how these negative thoughts may negatively impact rehabilitation outcomes. Further, clinicians may be better able to help individuals reframe these thinking traps to foster resilience and empowerment, and support their triumphant comebacks(6,7).

What are thinking traps?

Thinking traps, also known as cognitive distortions, are common patterns of biased or irrational thinking that can lead individuals to perceive reality inaccurately(4). These distorted thought patterns often emerge in times of stress, uncertainty, or adversity, making them particularly relevant in the context of injured athletes. Recognizing these thinking traps is crucial, as they can significantly impact an athlete’s psychological well-being, recovery process, and overall performance. For example, negative thoughts about the pain experienced during rehabilitation can affect the emotional response, such as fear of reinjury, which can then influence an athlete’s behavior, such as adherence to rehabilitation(8,9).

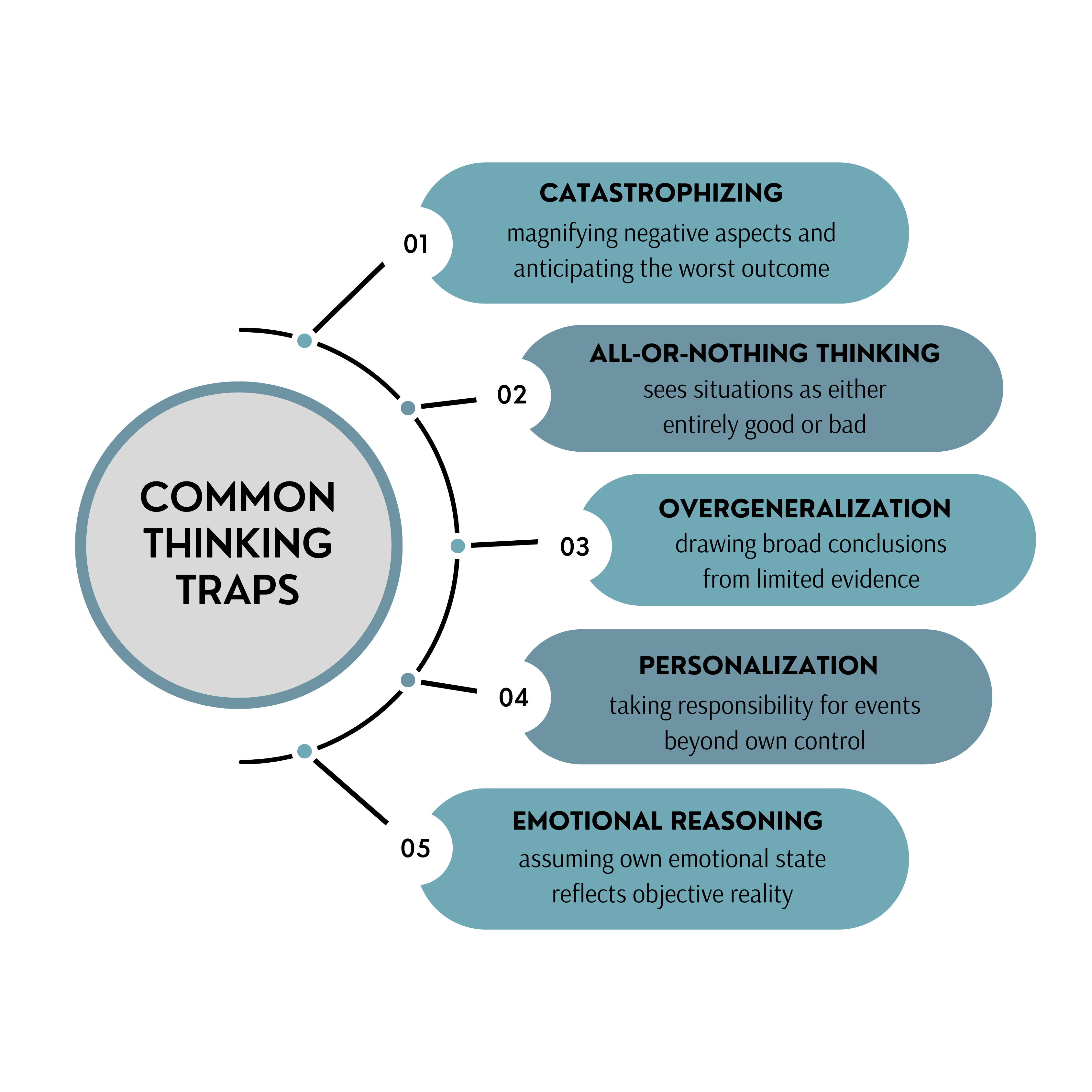

There are several types of thinking traps that athletes may experience, which include catastrophizing, all-or-nothing thinking, overgeneralization, personalization, and emotional reasoning. These cognitive distortions are like invisible hurdles that can significantly impede individuals’ path to recovery. By identifying these thinking traps, clinicians can empower athletes to confront and reframe their thoughts.

The impact of thinking traps on rehabilitation

Thinking traps can significantly impede an athlete’s rehabilitation progress and overall well-being. They can lead to increased stress, anxiety, and depression, hinder motivation, disrupt goal setting, and adversely affect the athlete’s relationship with their support network(10). For example, athletes who catastrophize may struggle to focus on the immediate steps needed for recovery. They may be preoccupied with thoughts of failure or permanent damage, making concentrating on the tasks difficult. When left unaddressed, these thoughts may prolong the recovery process. "It is imperative to let athletes know that as they progress through the injury-recovery process, it is normal to experience fluctuations in thoughts, which can also be negative in nature"(1).

Challenging thinking traps

Effective support for injured athletes begins with education. Clinicians can explain the concept of thinking traps in simple terms, helping athletes understand that their negative thoughts are not accurate reflections of reality but distortions. By sharing relatable examples, clinicians can show athletes how common these thinking traps are, reducing the stigma and normalizing the experience. Encouraging athletes to reframe their negative thoughts is a powerful strategy. Clinicians can guide athletes in recognizing when they’re falling into thinking traps and help them reframe those thoughts into more balanced and realistic perspectives.

1. Catastrophizing

This type of cognitive distortion involves magnifying the negative aspects of a situation and expecting the worst possible outcome. Injured athletes might catastrophize their injuries or their pain. Therefore, believing that they will never recover fully, their career is over, or they will never be pain-free. Clinicians should encourage athletes to look at the evidence for and against their catastrophic beliefs. Help them consider alternative, more positive outcomes based on realistic possibilities. For example, an athlete may think negatively, "This injury is the end of my career. I’ll never be able to compete again." This could be reframed to, "While this injury is challenging, many athletes have recovered from similar injuries. I can focus on my rehabilitation and work with my medical team to create a plan for a gradual and safe return to sports."

2. All-or-Nothing

Also known as black-and-white thinking, this distortion involves viewing situations as either entirely good or completely bad, with no middle ground. Injured athletes might fall into this trap by believing that if they cannot perform at their previous peak, any effort is futile, leading to reduced motivation. It is essential to help athletes see the grey areas between success and failure. One way of doing this may be to emphasize that progress is a positive step, no matter how small. For example, an athlete may present a negative thought such as "If I can’t perform at my previous level, there’s no point in trying at all." Clinicians could help an athlete reframe this by replacing this negative thought with a more neutral positive statement such as, "It’s natural to face setbacks during recovery. Even small progress is a step in the right direction. I can set achievable goals that help me regain strength and confidence, and I’ll keep building from there."

3. Overgeneralization

Overgeneralization involves drawing broad conclusions based on limited evidence or a single negative experience. Injured athletes may generalize a setback in their recovery to predict future failures, leading to demotivation. Clinicians can encourage athletes to examine whether their current experience applies to all situations. This would help them understand that setbacks are part of the process, not indicative of future failure. For example, an athlete’s negative thought may be, "I failed to reach my recovery goal today, so I’m destined to fail in everything." Helping athletes consider a more balanced perspective may encourage reframing this thinking trap. For example, clinicians could reframe it as "Recovery has its ups and downs, and not every day will be perfect. One setback doesn’t define your entire journey."

4. Personalization

This thinking trap occurs when individuals take responsibility for events beyond their control or attribute them to their actions. Injured athletes may personalize their injuries, feeling guilt or shame as if they caused the injury, affecting their self-esteem and recovery mindset. Clinicians should guide athletes to recognize that injuries are often beyond their control. This could shift their focus from blame to proactive recovery. For example, if an athlete presents a negative thought such as, "It’s my fault I got injured. I should have been more careful." The clinician may identify that this personalization is not helpful and, instead, help the athlete reframe this, such as, "Injuries are a part of sports, and they can happen to even the most careful athletes. Blaming yourself won’t help your recovery. Instead, focus on what you can control—following the rehabilitation plan and making safe choices."

5. Emotional Reasoning

Emotional reasoning involves if one’s emotional state reflects objective reality. If an injured athlete feels sad, they may believe their situation is hopeless despite contrary evidence. Clinicians should help athletes understand that feelings aren’t always accurate indicators of reality. Encourage them to seek evidence for their beliefs rather than solely relying on emotions.

Conclusion

Encouraging athletes to use these reframing techniques helps them develop a more balanced thinking pattern during recovery. In doing so, they may be better able to engage in rehabilitation activities and move towards effective action. Clinicians can play a role in helping th raise awareness of and challenge negative thinking patterns, to maintain motivation and approach setbacks with a constructive and adaptable attitude. Through psychoeducation and cognitive reframing, negative thinking patterns can be challenged to foster a more positive recovery experience. This comprehensive approach enhances the rehabilitation process and contributes to the athlete’s overall well-being and future success in sports.

References

- J of athletic training. 2015 50(1), 95-104.

- J Sports Med. 2016, 50, 145–148.

- Brit J of Sports Med. 2000, 34(6), 436-439.

- Cog Therapy of Depression. 1979, New York.

- The Sport Psych. 1990, 4(3), 261-274.

- Online J Sport Psych. 2002, 4.

- J of Clin Sport Psych. 2008, 2(1), 71-90.

- J Hum Sport Exerc. 2013, 8(4), pp. 1029-1044.

- J of Sport Rehab. 2005, 14(1), 20-34.

- Clin Psychology Review. 2020, 76, 101813.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.