You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Surf's up! Physical demands and injury in surfing

As the popularity of surfing continues to grow, so has the injury incidence. Yet, typically, practitioners know little about the demands and injury risks surfers face when riding the power of mother nature. Candice MacMillan explores the demands of surfing and outlines ideas around injury prevention.

Polynesians first practiced surfing over 800 years ago. This means that surfing is arguably the oldest extreme sport. Since the 1990s, the sport’s popularity has soared, with an estimated 37 million surfers globally(1). Commercialization of the sports lifestyle and its’ inclusion in the 2020 summer Olympics results in continued growth at recreational and professional levels(1,2).

Different formats of the sport exist, including:

- Body surfing (no board),

- Bodyboarding (prone on a small board),

- Surfing (standing on a surfboard),

- Stand-up paddle boarding (standing on a surfboard, propelled by a paddle),

- Tow-in surfing (towed onto a wave via jet-ski, riding a surfboard),

- Surf foiling (standing on board equipped with underwater foil).

The types of waves ridden vary in size, shape, bottom composition, and water temperature. "Big wave" surfers successfully paddle into waves as high as seven meters. Whereas tow-in surfers tackle waves as high as 15-25 meters with the assistance of jet skis(3).

With the evolution of surfboard technology, surfers enter more dangerous waters to pursue more powerful waves and practice and perform more complex acrobatic maneuvers(1,4). Together with the sport’s growing popularity, more risky maneuvres have led to an increase in injury incidence amongst surfers. Therefore, it is increasingly pertinent for clinicians to understand surfing injuries to best advise on how to prevent and manage them.

Physical demands of surfing

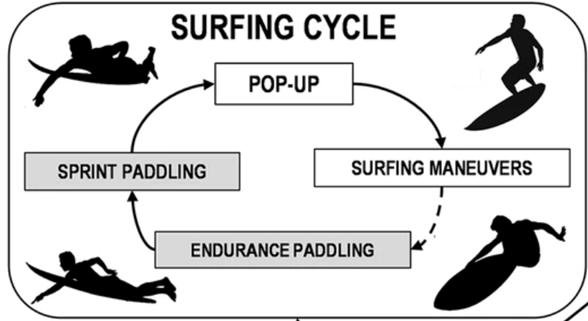

Surfing is an intermittent activity consisting of endurance and sprint paddling, pop-up, and surfing maneuvers (see figure 1)(5).

The sport demands bouts of high, moderate, and low-intensity exercise, soliciting aerobic and anaerobic metabolism(6,7). Time-motion analysis studies report that surfers spend 55% of their time paddling, 34% stationary, and 3–8% wave-riding. Furthermore, they may perform 2000 strokes during a two-hour session(6,7). The level of competition and environmental factors affect the demands and alter the activity percentages(6). Athletes record average heart rates (HR) of 139 beats/min and HR peaks of 190 beats/min, with 60% of total time spent between 56-74% of age-predicted HR maximum(6,7).

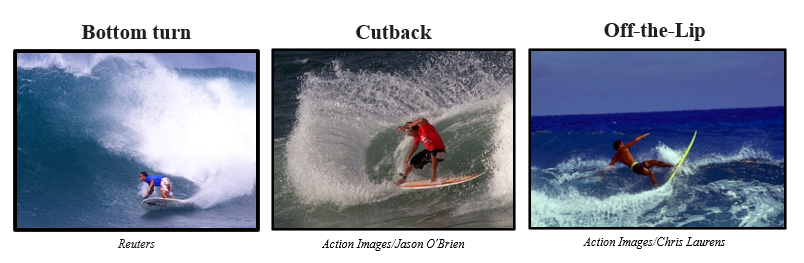

Surfing requires athletes to transfer force from their trunk musculature to maneuver a surfboard successfully with powerful, rotational movements on a wave’s surface(8). Both muscle strength and endurance are necessary for dynamic actions during competitive or free-surfing sessions(9). Considering the acrobatic nature of many of the maneuvers, the flexibility of the spine, hips, shoulders, and ankles is essential. In addition, foot positioning dictates the functional mechanics of the tricks during and after the bottom turn (see figure 2)(9).

During wave riding and trick execution, surfers rely on balance and leg strength(9). If they do not balance properly, the surfboard will either nosedive into the water or slip out from under them, resulting in them falling into the water and possible injury(9).

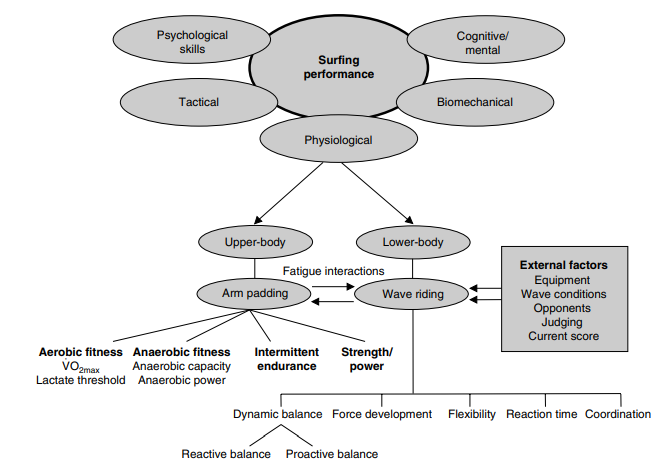

Competitive success is multifactorial and depends on the interrelationship between the surfer’s psychological, tactical, cognitive, technical, and physiological capacities (see figure 3)(6,7).

Surfing injuries

Surfing is relatively safe compared to other extreme sports(3). However, uncontrolled and often unpredictable ocean environments present unique risks to surfers. Additionally, sand, coral reef and rock breaks, water depth, wave size and type, water temperature, presence of other surfers, and local marine animals contribute to injury risk(2). Significant injury (i.e., resulting in lost surfing or work days and requiring medical attention) rates vary between 1.8 and 6.6 injuries/1000 hours, depending on the level of participation(2,3).

Acute injuries

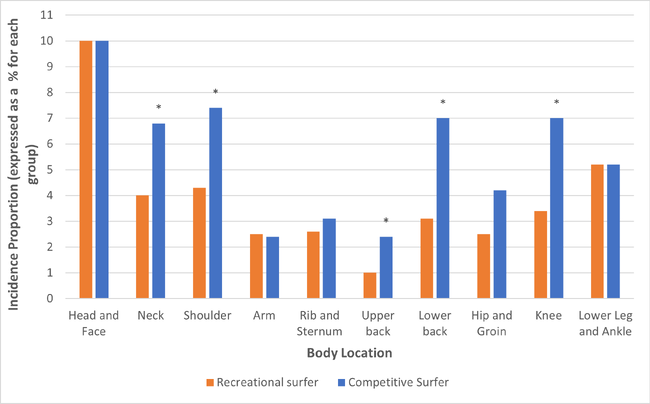

Lacerations are the most common type of injury, followed by sprains/strains, contusions, fractures, and dislocations(1,2,3). Body areas most frequently injured can differ slightly between recreational and professional surfers (see figure 4)(10). Acute injuries most often affect the head, neck, and face, followed by the lower limbs(1,2,3,10). Non-contact acute ligament injuries have increased as surfing maneuvers have become more acrobatic(1). Catastrophic and fatal injuries are rare but do occur. The most common catastrophic injuries requiring hospitalization are cervical spine fractures, spinal cord injuries, and complex facial lacerations. These may be accompanied by facial fractures, closed head injuries, and drownings(3,10,11).

Impact with the surfers’ own board, sea floor, or wave forces are the leading cause of acute injury(1,2,3). In big-wave surfing, most injuries result from being struck by the powerful cascading lip of a wave and being forcefully driven underwater. Shoulder dislocations, ruptured tympanic membranes, long bone and rib fractures, and lung barotrauma, resulting in hemoptysis and pneumothorax, occur in big wave surfing(2,3,10).

Overuse injuries

Chronic and overuse musculoskeletal surfing injuries are significantly more scarce than acute injuries. Overuse injuries are predominantly to the shoulder, neck, back, and knee(1,2,3). Most overuse injuries are highly correlated with prolonged periods of paddling and the performance of aerial maneuvers(1). Correct paddling technique requires the extension of the lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine to allow for shoulder circumduction. Therefore, lumbar and cervical paraspinal muscle injuries are common due to prolonged isometric hyperextension(1). In addition, the repetitive arm strokes in paddling predispose surfers to overuse shoulder injuries, including strains, which may result in tendon degeneration after years of surfing(1,3). The most common surgeries among surfers are repairing rotator cuff tears and superior labrum tears caused by overuse(3).

Injury prevention and conditioning

Surfboard modification and protective equipment

Considering that most surfing injuries occur when a surfer collides with a surfboard or the sea floor, modification in board design and using personal protective equipment can mitigate injury risk(2,3). For example, fins could be designed to break away with a significant impact and have rubberized or rounded edges. Similarly, board tails and noses could be rounded and covered with shock-absorbing materials(2,3). Technology advancements have made surfboards lighter and more maneuverable, allowing quicker changes in direction and aerial tricks. More agile equipment allows surfers to avoid contact with obstacles or react to wave-condition changes(2). Moreover, introducing surf-specific helmets in large hollow waves over shallow reefs, in strong-offshore winds when surfing alone, or in crowded conditions may mitigate head injury risks(2).

Conditioning

Surfers training under the guidance of a trainer and a periodized strength and conditioning program have an easier time advancing their sport-specific techniques and preventing injuries(9). To cope with the ocean demands, surfers must respond to periods of intermittent exercise, with different upper-body (i.e., arm paddling) versus lower-body (i.e., wave riding) demands. Surfing also requires great mental and cognitive activity in various environmental conditions(6,7).

Strength training should include exercises that promote rotational power, trunk muscle strength and endurance, and rotational flexibility (see table 1)(8). Considering the role of the feet and ankles in the execution of complex tricks, lower limb strength, and mobility training are vital. Practitioners can combine foot and ankle strength with balance and proprioceptive exercises when prescribing injury prevention programs. Surfers predisposed to shoulder injuries include those with scapular instability, muscle imbalances, or poor stroke techniques(1). Therefore, correcting periscapular muscle imbalances and stroke technique is pivotal to preventing chronic shoulder overuse injuries.

Table 1: Examples of trunk muscle exercises for surfers(8).

| Core 1 (sample) | Core 2 (sample) | Core 3 (sample) |

| Swiss ball crunch | Russian twist on ball | Reverse crunch on ball |

| Hanging leg raise | Jackknife crunches on mat | Alternating opposite arm/leg prone hyperextensions |

| Reverse hyperextensions on Swiss ball | Prone superman hyperextensions | Pelvic tilts on Swiss ball |

| Internal/external shoulder rotation | Overhead medicine ball throw | Internal/external shoulder rotation |

Practitioners must ensure that the intensity prescription matches the demands of surfing. For example, five sets of 10-12 repetitions per exercise promote strength and endurance.

When designing cardiorespiratory conditing programs, practitioners must consider the aerobic and anaerobic ratios related to the surfer’s age and participation level. In addition, they must consider the body position adopted during exercise as it alters the hemodynamic and performance parameters. This will impact the conditioning program design(6). On rare occasions, surfers are held underwater before surfacing and may need to hold their breath for as long as 40 seconds. This may be extremely challenging following a period of strenuous paddling. Breath-hold training can significantly improve static and dynamic apnea times, which may be life-saving(1,2). Anaerobic physical conditioning using high-intensity interval training also aids in breath-holding capacity.

Conclusion

Skin injuries are the most common type of surfing injury. Head, face, and neck injuries are the most common sites of acute injury, followed by the lower limb. Overuse injuries of the shoulder, lower back, and neck is increasingly common in surfers and associated with prolonged periods of paddling. Further research is needed to establish preventative measures for acute and overuse surfing injuries. As the sport’s popularity increases, this will need to be met with an improved understanding of the sport’s risks and safety. Professional supervision, training logs, and standardized equipment will help reduce training and sport-related injuries.

References

- Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(1):51-60

- Sports. 2020;8(2):25

- Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2020;10(02):171

- Clin J Sport Med. 2018; Publish Ahead of Print

- Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4566

- Sports Med. 2005;35(1):55-70

- J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:9

- Axel T. The effects of a core strength training program on field testing performance outcomes in junior elite surf athletes. California State University; 2013

- Strength Cond J. 2007;29(3):32-40

- PeerJ. 2021;9:e12334

- Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(5):S233-S237

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.