You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Snapping hip: a detailed explanation

Snapping hip, also referred to as coxa saltans, is diagnosed in at least 10% of the population, with dancers, runners, footballers and weightlifters beingcommonly affected(1). Snapping hip can be identified as being a sound or feeling of clicking close to the hip joint during movement, and is sometimes associated with pain. Indeed, you may have heard a patient saying ‘why do I get this clicking sound when I move my hips’?

Causes of snapping hip presentations are either intra or extra articular in nature and the purpose of the current article is to explore the anatomy of the hip joint and to identify causes of snapping hip syndrome. In addition, we will also cover the assessment of this condition, with differential diagnosis – along with treatment and management techniques.

Snapping hip mechanism

Snapping hip may be caused by factors arising from within (intra) or outside (extra) of the hip joint capsule. Causes of snapping hip from outside of the joint capsule generally derive from mechanisms medial or lateral to the hip. The medial mechanism is related to the iliopsoas tendon, which is involved in the friction of surrounding bony prominences including the iliopectineal eminence - the rounded protrusion on the superior rim of the pelvis where the pubic and iliac bones join.Other structures involved medially are the lesser trochanter and the anterior rim of the femoral head, and the associated joint capsule(1). Ultrasound studies have revealed that the ‘snap’ arises from the abnormal movement of the iliacus muscle against the pubic bone and iliopsoas tendon(2). When compared to non-snapping hips, this results in a snap of the iliacus tendon on the bone.

Ilipsoas anatomy

The iliopsoas is composed of the psoas major muscle and the iliacus, which both serve to flex at the hip joint by conjoining into one tendon. The iliacus however inserts just inferior to the lesser trochanter onto the femur, whereas the psoas major inserts directly at the lesser trochanter (see figure 1).The psoas major originates centrally from the anterior surface of the transverse processes, lateral border of the vertebral bodies, and the intervertebral discs of T12-L5(1). In contrast, the iliacus originates laterally from the iliac fossa, internal border of the iliac crest and the anterior sacroiliac, lumbosacral, iliolumbar ligaments.

Figure 1: The iliopsoas muscle and the associated bony landmarks

Snapping occurring laterally to the hip joint usually occurs due to friction of the iliotibial band (ITB) over the greater trochanter of the hip (see figure 2)(1). It has been noted that the tendon of the gluteus maximus tendon may be involved; thickening of the anterior aspect of the gluteus maximus tendon or posterior aspect of the ITB increases the ‘snapping’ sound. Elite ballet dancers frequently present with snapping hip due to the extreme ranges of motion performed in dance moves, with 90% of participants reporting snaps, cracks and clicks(3). External rotation and abduction to 90° predisposes a hip joint to increased incidence of snapping, and such a position is commonly performed by footballers and ballet dancers(3).

The ITB has two muscular attachments with the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) and the gluteus maximus, providing muscular attachment to the pelvis. The TFL originates at the outer rim of the iliac crest, the anterior superior iliac spine and the anterior border of the ilium. The gluteus maximus in contrast originates at the gluteal line of the ilium, the sacrospinalis tendon, the dorsal surface of the sacrum, coccyx, and sacrotuberous ligament. The gluteus maximus inserts into the gluteal tuberosity as well as the ITB, along with the TFL.

Figure 2: Lateral hip complex and the associated bony landmarks

Dysfunction of the iliopsoas muscle results in an anterior-directed force on the femur, and consequently, the acetabulum and the surrounding labrum(4). Intra-articular snapping affects a number of structures including the labrum, and articular cartilage fragments (as well as fracture fragments), which predisposes to the occurrence of loose bodies(1). Patients with intraarticular snapping are more likely to report sensations of catching, painful clicking or locking, and a sharp stabbing sensation(1).

The gold standard for assessing an intraarticular hip joint pathology is a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrography. When researchers at the University of Yamanashi, Japan, studied 31 hips by MRI arthrography, they found that a torn acetabular labrum was the cause of intra-articular snapping hip in 80% of cases(5).

Assessment techniques

An important indicator for a provocation test for a snapping hip is the sound or the feeling of a ‘snap’in accordance with or without pain. Movement tests for the medial hip joint are most effectively performed through flexion into extension whilst lying in supine (see figure 3)(6). During these tests, it is common for the snapping to be heard or felt at around 30-45 degrees of hip flexion, and may be reduced by applying pressure to the iliopsoas tendon over the pelvic brim. It is essential to not misinterpret medially occurring hip pain snapping for an intra-articular joint pathology(6). Therefore, if snapping presents medially, further testing is warranted. For example, ultrasound-guided iliopsoas bursa or peritendinous injections can indicate the cause of pain by providing pain relief(7).Figure 3: Hip snapping pain assessment

The hip is passively extended from a flexed, abducted and externally rotated position into extension with adduction and internal rotation(6).

Due to the location, a lateral snapping of the hip is often more easily distinguished from a joint disorder than a medially snapping hip. The patient may describe a sensation as though the hip is dislocating or subluxing, but rather than the joint being unstable, he/she is more likely experiencing the feeling of the tensor fasciae latae moving across the greater. This has been given a term of ‘pseudosubluxation’ and is more of a jerking movement felt on the outside of the hip(1).

Similar to medial snapping, the patient may be able to describe or actively perform the snapping themselves. To assess for lateral hip snapping, have the patient lying on their side, with the leg to be assessed uppermost. Passively flex at the hip and knee joints, from end-of-range hip extension into full flexion and back into end-of-range hip extension, whilst palpating at the greater trochanter (see figure 4).

An additional assessment of the abductor complex is to perform the Ober’s test (again in side lying) with the uppermost leg being assessed(6). To perform the test, lower the patient’s knee by supporting them by the lower leg and pelvis. If the knee remains elevated at hip height, this indicates muscle shortening of the abductor complex. If the knee lowers then this indicates good muscle length of the abductor muscles.

In summary, a useful rule of thumb is if you can hear the snap it is relating to the medial hip and if you can see the snap then it is related to the lateral hip.

Figure 4: Ober’s test

Passive flexion and extension while assessing for lateral snapping of the hip.

Background information about the patient is also useful. A patient with a lateral snapping hip will often present with difficulty on climbing stairs, running, carrying heavy loads out in front or on their back, or even playing golf. In contrast, a patient with a medial snapping hip will complain of symptoms on running, sit to stand and getting in and out of a car. These questions should be carefully constructed during a subjective assessment to assist in forming an objective assessment. During the objective assessment it is also essential to identify if pain at the hip is due to hip pain specifically, or whether it is related to radicular lumbar pain(8).

Treatment and management

From a conservative management viewpoint, effective methods for reducing extraarticular snapping symptoms will focus on lengthening the associated muscles(1). For internal mechanisms, stretching the iliopsoas (see figure 5) and for the external mechanisms, stretching the tensor fasciae latae and the iliotibial band is recommended. Deep tissue massage and active release techniques of the hip flexor and the associated structures including the lumbar spine are also considered to be effective, as is the use of ice and heat(1). Neuromuscular retraining of specific muscles is also required to improve muscle firing patterns around the hip complex. If symptoms persist following a conservative program, then surgical lengthening of the psoas or iliotibial band is indicated.Figure 5: Stretching the iliopsoas

Case study

A case report of a 16-year old dancer with a two-year history of lateral right hip pain and a snapping sound was reported in the Journal of Canadian Chiropractic Association(9). Her pain was rated at 4/10 (0 being no pain and 10 being unbearable pain) and wasn’t related to a particular mechanism of injury. Previous treatments consisted of a year of chiropractic sessions and stretching of the ITB and hip flexors, but this had little effect. Observation revealed that the patient had genu valgum (better known as knock knees) with excessive pronation in both ankles. Ranges of movement were pain free and symmetrical for the lumbar spine, hips, knees and ankles. No pain with clicking or locking was observed at the end-range of hip flexion with added internal or external rotation, which ruled out the involvement of a labral tear.Manual muscle testing identified a weakness in the hip abductors of the involved leg, and with increased TFL muscle activity during side lying abduction. In side lying passive flexion and extension with the involved leg uppermost, an audible and palpable click was identified as the ITB passed over the greater trochanter, reproducing the lateral hip pain. Tenderness and tension was found on palpation of the right posterior gluteus medius fibres, the greater trochanter, the TFL, gluteus maximus and ITB. Pain was also noted in the right adductor muscles on the inner thigh. Video analysis highlighted excessive hip adduction during the stance phase of walking and jogging. A diagnosis of external snapping hip was provided, with the ITB and gluteus maximus fibres snapping over the greater trochanter.

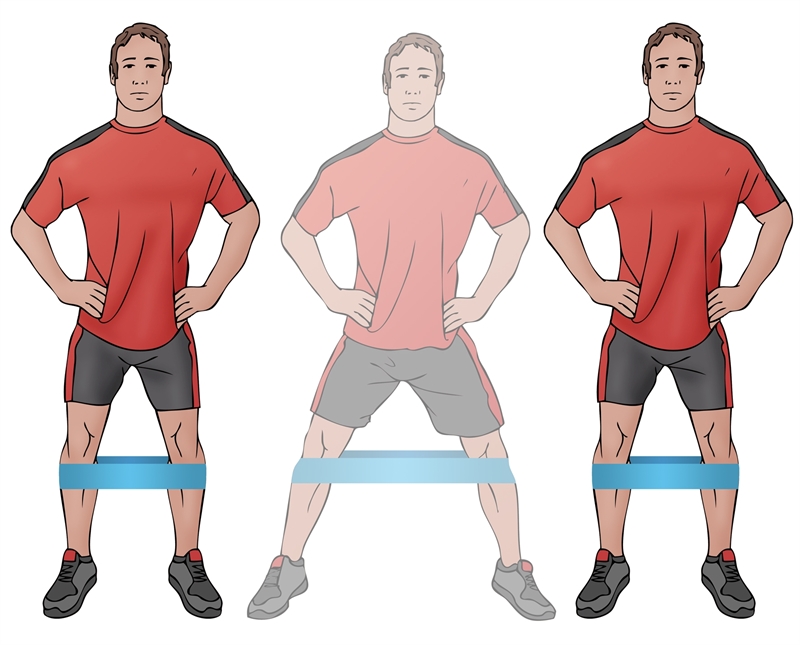

Treatment consisted of active release techniques of the TFL, ITB, gluteus maximus/medius, and the adductors and gracilis muscles. This treatment yielded a 50% improvement after the first appointment, which progressed over four treatment sessions, eventually resulting in a 100% improvement in the pain. A programme for lateral hip stability was undertaken to improve muscle firing patterns of the lateral hip complex (see figure 6.) The patient was pain free on all meaningful tasks and remained pain free at one year follow up.

Figure 6: Pelvic stability program exercise

Resisted lateral walking exercise to promote pelvic stability.

Summary

Snapping hip can be related to intra or extra-articular factors or even both. Thorough assessment should exclude hip joint and lumbar spine pathology. Pain may or may not be present; if pain is a primary symptom then a conservative (or in extreme cases a surgical management) programme must be introduced to prevent further joint pathology. With snapping hip symptoms being so prevalent amongst the athletic populations, management programmes may be required to reduce the onset of pain in the future.References

- Ath Train, May, 2010, 2, 3, 186-190

- Am J Roentgenol. 2008,190, 3, 576-581

- Am J Sports Med, 2007, 35,1, 118-126

- J Radiol Case Rep. 2011, 5, 10, 1–6

- The J of Arthro and Rel Surg, Sept 2005, 21, 9, 1120 – 1125

- N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2007 Nov, 2, 4, 231–240

- AJR Am J Roentgenol.2005 Oct, 185, 4, 940-3

- Am Fam Physician.2014 Jan, 1, 89, 1, 27-34

- J Can Chiropr Assoc, 2007, 51,1, 23 – 29

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.