You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Serratus Anterior and Overhead Athletes: Understand its Importance!

Dysfunction in the serratus anterior can lead to shoulder injuries and affect performance. In the first of a two-part series, Chris Mallac looks at its anatomy and biomechanics.

Feb 20, 2020; Blue Jays infielder Vladimir Guerrero Jr. (27) throws the ball to first base during the spring training workout. Credit: Jonathan Dyer-USA TODAY Sports

Shoulder pain is a common complaint in overhead athletes involved in sports such as swimming, tennis, and throwing sports. Overhead arm movements place high demands on the shoulder complex and require muscular activation around both the scapula-thoracic joint and the glenohumeral joint. Researchers report that abnormal biomechanics of the shoulder girdle and repeated overhead movements can lead to injuries in overhead-throwing athletes(1).

In particular, muscular imbalances around the shoulder complex in the form of altered activation patterns and inherent myofascial restrictions may lead to diminished scapular control and dyskinesis, resulting in glenohumeral joint injuries, such as instability and impingement(2).

The serratus anterior (SA) is one of the muscles that provide a link between the shoulder girdle and the trunk. Its dysfunction likely plays a role in shoulder pathologies(3,4). The SA is a prime mover of the scapula and contributes to normal scapulohumeral rhythm and motion(4). It has a large moment arm which produces upward rotation and posterior tilting as a result of its insertion on the inferior and medial border of the scapula. Poor activation of the SA muscle may result in reduced scapular rotation and protraction. This dyskinesia may trigger a relative anterior-superior translation of the humeral head in relation to its glenoid articulation, causing subacromial impingement and rotator cuff tears(5).

Anatomy and Biomechanics

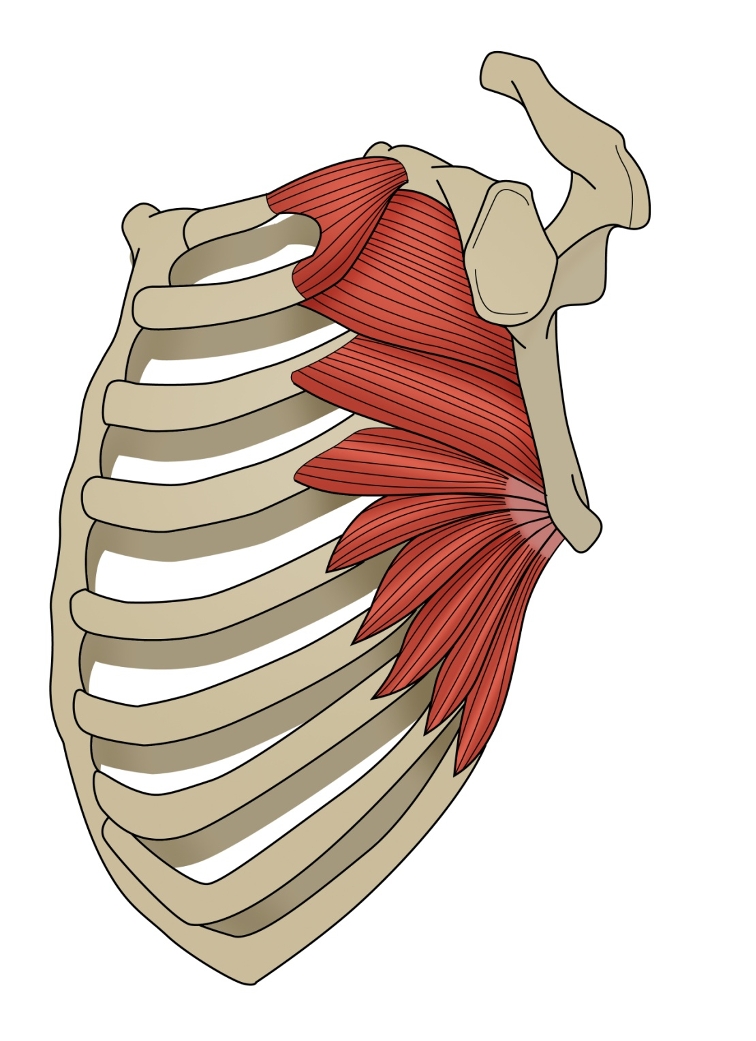

The SA is a flat sheet of muscle originating from the lateral surface of the first nine ribs (see figure 1). It passes posteriorly around the thoracic wall before inserting into the anterior surface of the medial border of the scapula(6). Overall, the main function of the SA is to protract and rotate the scapula. This movement provides optimal positioning of the glenoid fossa for maximum efficiency for upper extremity motion(7). The SA consists of three functional anatomical components(8,9):

- The superior component - Originates from the first and second ribs and inserts into the superior medial angle of the This component serves as the anchor that allows the scapula to rotate when the arm is lifted overhead. These fibers run parallel to the 1st and 2nd ribs;

- The middle component - Originates from the second, third and fourth ribs and inserts onto the medial border of the scapula anteriorly (sandwiched between the scapula and ribs). This component is the prime protraction muscle of the scapula;

- The inferior component - originates from the fifth to ninth ribs and inserts on the inferior angle of the scapula. The fibers form a ‘quarter fan’ arrangement, inserting onto the inferior border of the scapula. This third portion serves to protract the scapula and rotate the inferior angle upward and laterally. Inman (1944) proposed that the lower part of the serratus anterior is the stabilizer of the inferior border of the scapula, and works with the lower trapezius to create a force couple to upwardly rotate the scapula during overhead movement(10).

Figure 1: Serratus anterior overview

Serratus Anterior Functional Roles(9)

- Upwardly rotate the scapula during shoulder abduction, particularly from 30 degrees of shoulder abduction onwards;

- Stabilize and protract the scapula during shoulder flexion movements;

- Rotate the inferior angle anteriorly (posterior tilt of the scapula);

- Stabilize the scapula against the thorax during forward pushing movements in order to prevent the scapula ‘winging’ (see below);

- Hold the medial border of the scapula firmly against the thorax so that with the hand fixed, it can displace the thorax posteriorly during a push-up.

In the athlete, specific movements require precise function of the SA to achieve either full scapular protraction and/or upward rotation. Examples of athletic endeavors requiring this SA function include:

- Throwing a punch in boxing – The SA helps to achieve maximum reach of the arm. Hence, the SA is often referred to as the ‘boxer muscle’.

- Absorb the impact of a punch in boxing – The SA braces the scapula on impact with the punch. This allows maximum transfer of force from the lower limbs through the torso to the punching arm. If the scapula was to ‘collapse’ into retraction upon impact of the punch, the boxer would lose power in the punch.

- Maximum reach for hand entry in swimming – The SA again lengthens the arm to enable the athlete to take the greatest stroke possible.

- A tennis player serving - The overhead athlete such as a tennis player needs full upward rotation in the act of serving.

- Extend reach during the catch phase of the rowing stroke - The sweep style rower needs full protraction on the ‘long’ side to achieve necessary reach.

- Baseball pitcher’s follow through - In baseball, the pitcher needs high levels of protraction during the follow through of the baseball pitch. Similarly in other throwing events in athletics.

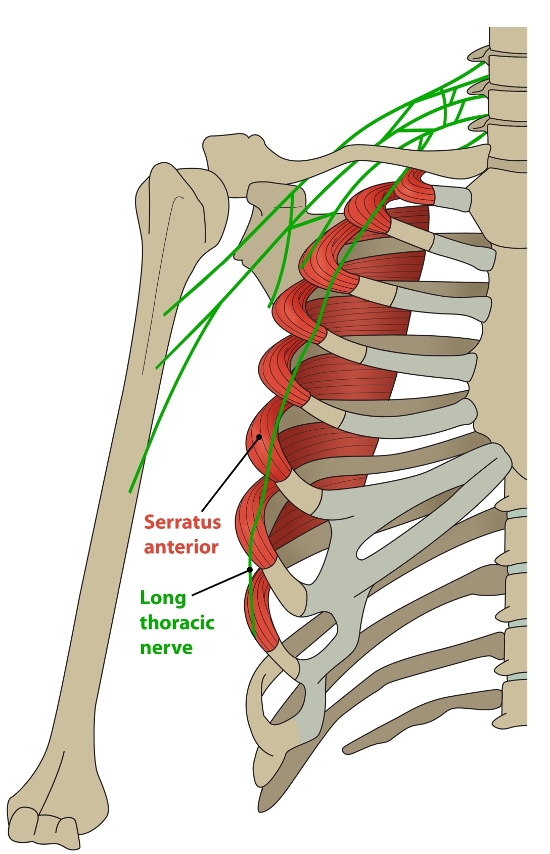

The SA is innervated by the long thoracic nerve, which originates from the anterior rami of the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical nerves (see figure 2)(7,8). Branches from the fifth and sixth cervical nerves pass anteriorly through the scalenus medius muscle before joining the seventh cervical nerve branch that courses anteriorly to the scalenus medius. The long thoracic nerve then dives deep to the brachial plexus and the clavicle to pass over the first rib. Here, the nerve enters a fascial sheath and continues descending along the thoracic wall’s lateral aspect to innervate the SA muscle.

Figure 2: Long thoracic nerve(11)

Serratus Anterior Dysfunction and Scapula Dyskinesis

Proper positioning of the humerus in the glenoid cavity during movement, known as scapulohumeral rhythm, is critical to the proper function of the glenohumeral joint during overhead motion. A disturbance in normal scapula movement may cause inappropriate positioning of the glenoid relative to the humeral head, resulting in an impingement or instability(2,12,13). Small changes in activation in the muscles around the scapula can affect its alignment, as well as the forces involved in upper limb movement(14). One of the primary muscles responsible for maintaining normal rhythm and shoulder motion is the SA(15).

Actively assisting a patient’s scapula into an ‘ideal’ posture by reducing the anterior tilt, often reduces pain and increases strength in the shoulder during overhead activities(16). Since the SA actively positions the scapula into a posterior tilt during overhead activities, it is assumed that an anteriorly tilted scapula is a result of SA dysfunction. A weak SA positions the scapula in a downwardly rotated and anteriorly tilted position, making the inferior border more prominent or winged. Pathological inhibition of the SA from nerve damage or an imbalance between the SA and the other protracting muscle, the pectoralis minor, may also result in a winged scapula. Scapular winging may precipitate or contribute to persistent symptoms in patients with orthopedic shoulder abnormalities(17,18).

This scapular winging is best appreciated when watching the scapular position during a push-up exercise. Often, if the winging is due to a muscle imbalance and the primary scapula stabilizer is the pectoralis minor, it usually corrects if the patient is asked to ‘plus’ and protract the scapula. To cue the athlete to perform this plus maneuver, once they are in the plank position, ask them to push the floor away. This is also referred to as a scapular pushup. If the wing disappears then the cause is most likely muscle imbalance, if it remains then it may be a pathological inhibition of the SA due to an injury to the cervical nerve root or long thoracic nerves (see figures 3-6).

Figure 3: Scapular winging on push-ups bilaterally

Figure 4: Winging corrects on execution of a ‘plus’

Figure 5: Scapular winging on push up bilaterally (right greater than left)

Figure 6: Left scapula corrects with ‘plus’ however note the right is still winged

Research Review

- A comparison between the strength of contraction of the trapezius and the SA in people with and without shoulder pathology found that the upper trapezius shows increased activity during arm elevation and lowering, and the SA shows decreased activation at some elevation angles (usually 70-100 degrees) in people with an injury(19).

- When the muscle activation patterns of swimmers with shoulder pain is compared to those without, the middle and lower SA show decreased activity in all phases of swimming motion in the painful shoulders. Is this the cause of the shoulder pain or a consequence of a painful shoulder whereby the swimmer uses compensatory muscle activation patterns(20)? Studies could not determine.

- Similarly, other researchers have found a ‘latency’ or activation delay in the SA in the painful shoulders of swimmers as they raise their arms in the scapular plane(21).

- Ludewig and Cook (2000) hypothesized that patients with decreased SA activation suffer from shoulder pain or instability, and that an increase in lower trapezius activity is an attempt to compensate for the decreased serratus anterior activation(2).

- Lin et al (2005) studied subjects with various types of shoulder dysfunction and found decreased serratus anterior activity and increased upper trapezius activity, without a change in lower trapezius activity, in injured shoulders when compared to normal subjects(22).

Scapular position also impacts the ability of the rotator cuff to function. Excessive anterior tilt, internal rotation, or excessive elevation decrease rotator cuff activation and cause an unequal distribution of tension along the tendons. Such situations impair the optimum length-to-tension ratio of these muscles, leading to a loss of stabilization and increasing the chance of muscular disruption or degeneration(23).

A strong and conditioned serratus anterior muscle improves performance in sports such as swimming, throwing, and tennis. A fatigued serratus anterior muscle reduces scapular rotation and protraction. The dyskinesia likely allows the humeral head to translate anteriorly and superiorly, and possibly leads to secondary impingement and rotator cuff tears. Exercises to strengthen the SA is the topic for the second part of this series.

References

- Athl. Train. 2007; 42(2):311-319.

- Phys Ther. 2000;80(3):276–291.

- J OrthopSports Phys Ther 1999. 29: 574–586

- J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1996. 24: 57–65

- Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1994;20(6):307-318.

- Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc; 2005. p. 633–47.

- Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999. 368:17–27.

- J BoneJoint Surg 1979;61:825–32

- Simons et al (1999) Travell and Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. Volume 1 Upper Half of the Body (2nd edition). Williams and Wilkins. Baltimore.

- J Bone Joint Surgery. 1944. 26(1); 1-30.

- Am J Sports Med 2004; 32:1063–76.

- J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1993. 18: 427–432

- Kibler WB: Normal shoulder mechanics and function. Instr Course Lect 46: 39–42, 1997

- Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):542-9

- Phys Ther 1994. 75: 194–202

- Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2008. 38(1). 4-11

- Contemp Orthop 1991. 22: 525–532

- Physiol Ther. 2007;30(1):69-75

- Am J Phys Med 1977;56(5):223–40

- Am J Sports Med1991;19(6):577–82

- Int J Sports Med 1997;18(8):618–24

- J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2005;15(6):576–586

- Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(1):60-9

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.