You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Strengthen to Succeed: The Power of Land-Based Training for Injury-Prevention Dressage Athletes

Strength training for dressage athletes plays a vital role in injury prevention by improving overall body strength, stability, and joint integrity, reducing the risk of injuries associated with the demanding movements and repetitive nature of the sport. Christie Wolhuter discusses the importance of land-based training when working with dressage athletes.

Equestrian - Germany’s Jessica Von Bredow-Werndl rides Tsf Dalera BB during the FEI Grand Prix dressage event Jessica Gow/TT News Agency via REUTERS

The ultimate goal of the rider, no matter what the discipline, is to move harmoniously with the horse. This is a monumental task for the central nervous and musculoskeletal systems. Most athletes train outside of the discipline they compete in (e.g., land training for swimmers), yet there is very little evidence of this in equestrian. Like any sport, the goal is to apply specificity to one’s training, which is challenging with equestrian athletes as the exact mechanism of how a rider’s musculoskeletal system can interact and influence the horse is poorly defined, especially at the elite level(1). Another difficulty in researching the horse-rider dyad is the large number of variables that affect the relationship and the ethical challenges in conducting animal research(1).

The ‘ideal’ dressage position has been debated among riders, trainers, and judges for centuries. While there are general principles and guidelines to follow, achieving the perfect dressage position is subjective, influenced by factors such as the rider’s physique, the horse’s conformation, and the specific requirements of the movement or level of competition. Thus, despite ongoing discussions and evolving understanding, a definitive and universally accepted answer to what constitutes the ‘ideal’ dressage position remains elusive.

The Greek Philosopher Xenophon, largely regarded as the father of Equitation Science, wrote in his book, The Art of Horsemanship, over 2350 years ago – “The rider should use his seat to control the horse” and described the now ‘classical seat’ as “not that of a man seated on a chair, but rather the pose of a man standing upright with his legs apart.” Xenophon also said, “The rider should accustom the whole body above the hips to be as supple as possible” (2).

So what is considered the ideal modern dressage seat?

- The most accepted stable position, where the aids can be applied correctly, is the ear-shoulder-hip-heel line (see figure 1). There is some fair criticism that this is not the only position where a rider can effectively influence the horse, but it is the most widely accepted.

- There should be even pressure on each seat bone. However, when needed, the rider can put slightly more pressure on one seat bone.

- The seat should be independent, meaning the rider is dynamically stable and can move each body part independently. For example, the hands should be able to move independently of the trunk rather than primarily being used to balance the rider by holding on to the horse’s head via the reins(3).

- The upper back should remain relatively still while the pelvis moves rhythmically with the horse’s movements(4). In sitting trot, the pelvis very slightly tucks anteriorly and posteriorly, while in canter, the tilt resembles a rhythmic ‘polishing’ of the saddle seat.

- Experienced riders can improve the consistency of the horse’s movements(3).

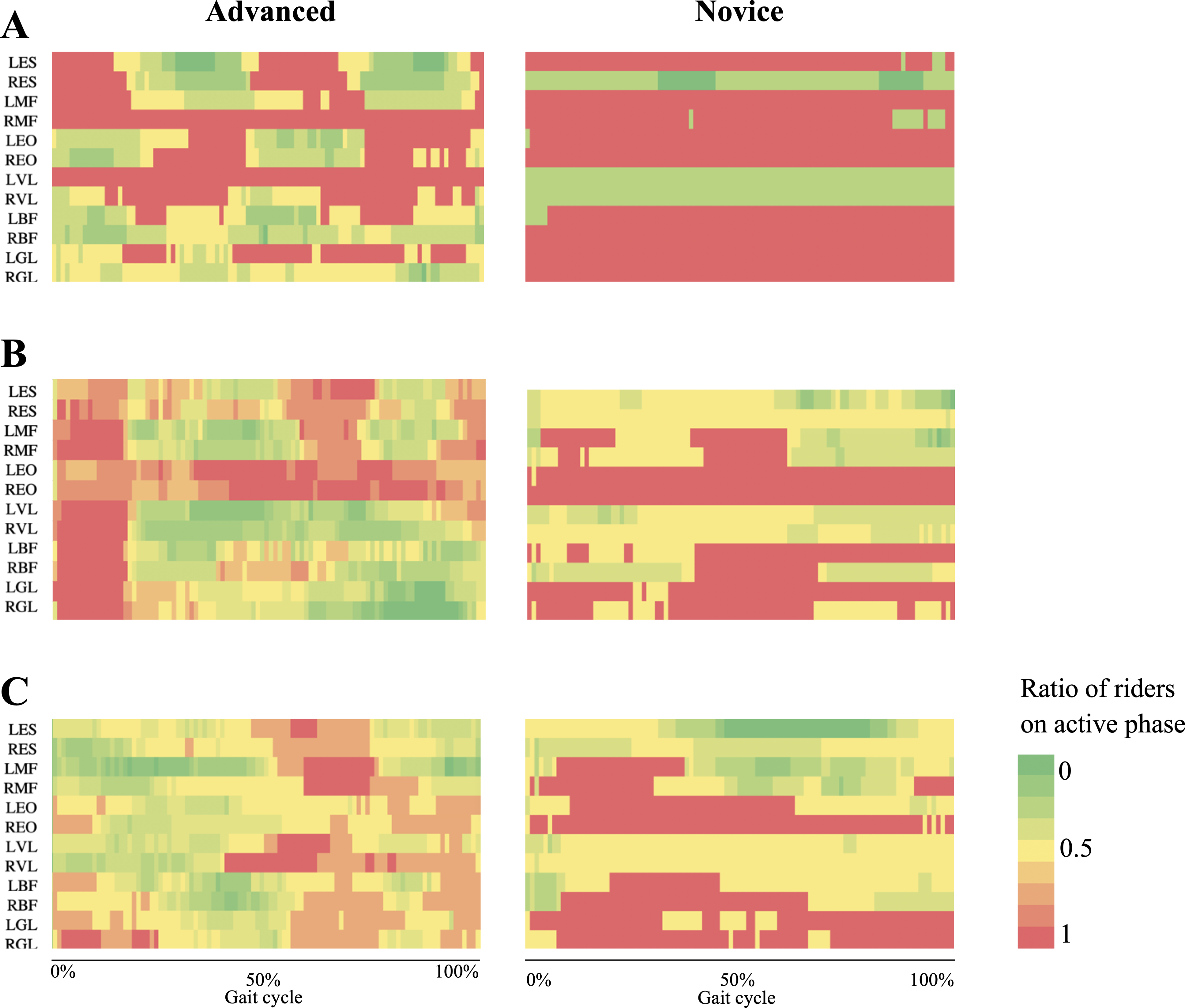

To effectively develop an out-of-saddle training program, practitioners must understand how a more advanced rider can achieve synchronicity with the horse. Researchers at the University of Primorska in Slovenia researched how an advanced rider interacts from a neuromuscular level with the horse compared to novice riders. The study used surface EMG to determine differences in muscular contraction levels and patterns, synchronized with inertial data from the horse of six novices and nine professional riders(5). The results showed that advanced riders demonstrated better intermuscular coordination than novices and could stabilize their position via contralateral muscular contractions.

Using principal component analysis (PCA), a method of extraction used to find patterns in muscle synergies, the authors found that the advanced group could synergistically contract both sides of the body simultaneously. In contrast, the novice group seemed to end up using one side of their body at a time. The novice group also showed higher co-contraction levels of agonist and antagonist muscle groups, known as reciprocal contraction. Reciprocal contraction likely occurs when uncertainty exists in the desired motor task and when a compensatory force contraction is perceived to be required(6). This compensatory muscular pattern in riding is brought about by the unexpected perturbations of the horse’s gait cycles. This shows the novice rider attempts to stabilize their center of gravity (COG) by bracing, which can restrict the horse, as the rider cannot move synergistically(5). When a rider braces against a horse’s movement, it results in bouncing in the saddle and, often, a forward lean(4).

The authors hypothesized that the advanced group might better split neural motor output contralaterally, whereas the novice group seemed to use one side of their body at a time. This means that the novice riders studied had a more on/off output from the motor cortex, which could compromise the general tone of the body(5).

Interestingly, the walk and canter gaits showed the greatest difference between the advanced and novice groups. The active phase (AP), as demonstrated in the heatmap, is defined as the duration between the onset and the offset of individual muscle activity (see figure 2)(5). This heatmap represents the ratio of muscular contraction of individual muscles in one full stride, from walk (A) to canter (C). In walk, the advanced group showed alternating patterns of activation of the trunk flexors (external oblique) and trunk extensors (multifidus and erector spinae). In contrast, the novice group demonstrated a more consistent contraction across multiple muscles throughout one walk stride. At the trot and canter, the advanced riders again showed a similar rapid pattern of activation and relaxation of the trunk and leg muscles(5). It is also interesting to note the timing of muscular contraction across each stride cycle is markedly different between the advanced and novice group. In a challenging gait like the canter, the advanced group showed overall lower levels of muscular contraction, as represented by the green in the heatmap.

Land-based training

Land-based strength training plays a crucial role in enhancing the performance of dressage athletes. They can improve their stability, balance, core strength, and overall body control by incorporating specific exercises and routines, leading to greater harmony and effectiveness in the saddle. This form of training also helps prevent injuries, increases muscular endurance, and supports the development of the physical attributes necessary for executing the demanding movements and precise cues.

In addition to its performance-enhancing benefits, land-based strength training is valuable for injury rehabilitation and prevention. Dressage athletes recovering from injuries can use targeted exercises to rebuild strength, flexibility, and coordination while addressing any imbalances or weaknesses that may have contributed to the injury.

Range of movement

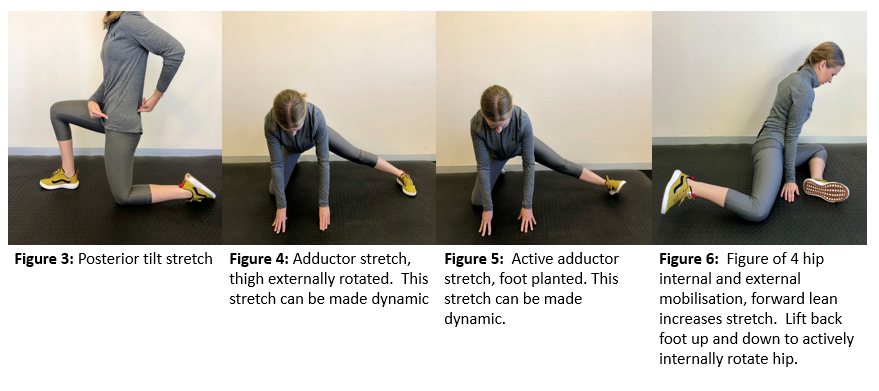

Range of movement (ROM), particularly in the hips, is essential, as the rider spends most of training and competition seated in the saddle, unlike showjumping, where they rise out of the saddle into a ‘jumping position.’ The rider’s seat has to influence the horse, and if the rider has restricted, weak hips, they are less able to apply their aids effectively. The femur has to be able to actively and passively internally rotate to allow the rider to drape the thigh against the saddle and use leg aids behind the horse’s girth area (see figures 3 – 6).

Proprioception and motor control

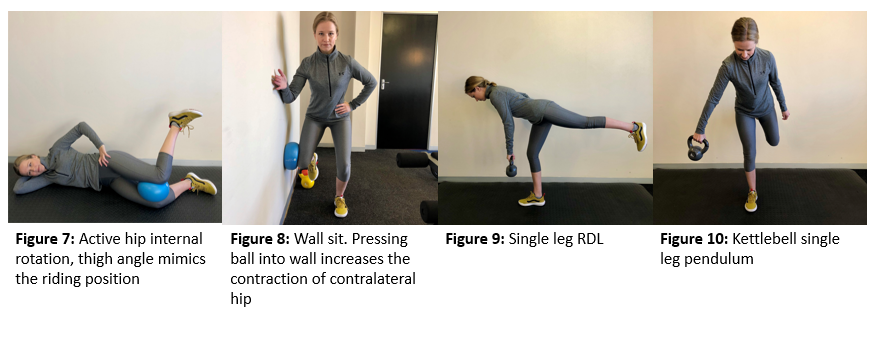

The goal of out-of-saddle proprioception and motor control training is to improve the rider’s balance and coordination. Therefore, it is crucial to perform both unilateral and bilateral exercises(5). Bilateral activities include any exercise that uses both sides of the body in the same pattern (e.g., squat and deadlift). A rider wanting to improve their seat position must use both sides of their body in a coordinated manner (see figures 7 – 10).

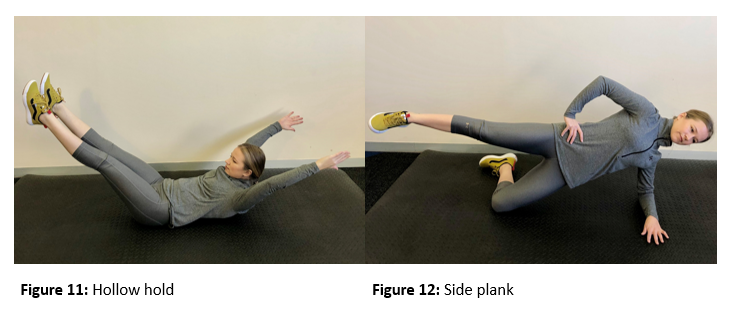

Lumbopelvic stability

Table 1: Anti-rotation exercise examples for dressage

| Anti-extension | Anti-flexion | Anti-lateral flexion | Anti-rotation |

|

|

|

|

References

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.