You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Returning youth to sport following lockdown

Many nations are starting to ease strict lockdown rules, allowing life to return to normal after the novel coronavirus pandemic. Professional sportspeople and weekend warriors alike are chomping at the bit to get out there and compete again. The internet is booming with articles describing how to return to sport safely. But, few consider this process from the perspective of youth sport. Youth sport is fundamentally different from adult sport, and therefore deserves particular considerations. As the adage goes, “Children are not small adults.”

How are youth sports different?

Huge numbers of youths regularly participate in sport. A 2013 ESPN article stated, “Youth sports is so big that no one knows quite how big,” but went on to estimate that 21.5 million youths between the ages of 6 and 17 played organized sport in America(1). In Australia, the highest rate of sports participation among any age group is in 10 to 14 year old’s, and this pattern is likely to be similar around the world(2).The numbers of participants in youth sports is larger than in adult sports, and the nature of youth sports is also different. At a population level, adults participate mostly in endurance exercise (running, cycling, swimming), strength training, and commercial exercise classes, with few remaining involved in team sport beyond their early twenties. Whereas, youth play team sports almost exclusively. As a result, youth sport requires different skills and physical attributes, and thus carries unique injury risks. Differences in motivation are also present, with adults taking part primarily to maintain their health and wellbeing, while children play to have fun, compete, and improve their skills(3). Both groups use sports as an opportunity to socialize.

The risks and benefits of returning to youth sport

Physically active children are healthier, do better at school, and have improved mental health(4). On this basis, a return to youth sports is desirable, particularly given the stressful conditions imposed on young people by the coronavirus lockdown. However, there are two key risks to consider in returning to sport. Firstly, there is a risk relating to the virus itself. Resuming youth sports would likely affect infection rates on a national level. While the chances of infection with COVID-19 are lower in children than in adults, they can still suffer severe effects and pass the virus to other groups at higher levels of risk(5).Like all industries, youth sports must follow the regulations and restrictions set out by their respective governments and enforce risk-mitigation protocols. Such measures include participant screening, social distancing, personal protective equipment, and frequent sanitization of equipment and facilities.

The second consideration is the risk of injury in returning to sport after an extended period of reduced physical activity. Despite the many benefits of sport involvement, the risk of injury in youth sports is high. A sports injury often leads to reduced participation in sports and increases the likelihood of obesity and osteoarthritis(6). The elevated injury rates in youth sports are likely related to the nature of the games they play. Jumping, maximal accelerations and decelerations, rapid changes of direction, and expressions of maximal speed as the players try to outmaneuver each other are inherent in team sports. These high-intensity movements often exceed the capacity of the tissues involved to manage the forces generated and lead to injury. Appropriate training can greatly reduce the risk of injury from executing these high-intensity movements(6).

Mitigation of detraining

The first step in safely returning youths to sports participation is understanding the effects of isolation due to lockdown on their physical states, such as reduced muscle mass, neuromuscular function, aerobic capacity, and insulin sensitivity(7). Maintaining a regular diet in the face of reduced physical activity (and therefore, energy expenditure) is also likely to result in increased body fat(8).Children continued to grow during the lockdown period. There can be dramatic changes in body size since they last played a sport, especially in adolescents. Upon return, children could display substantial reductions in relative strength (pound for pound strength per unit body mass). Attempting to decelerate bodies that are now able to generate more momentum (as a result of increased body mass) with reduced force-production capabilities (as a result of reduced strength) increases the risk of injury.

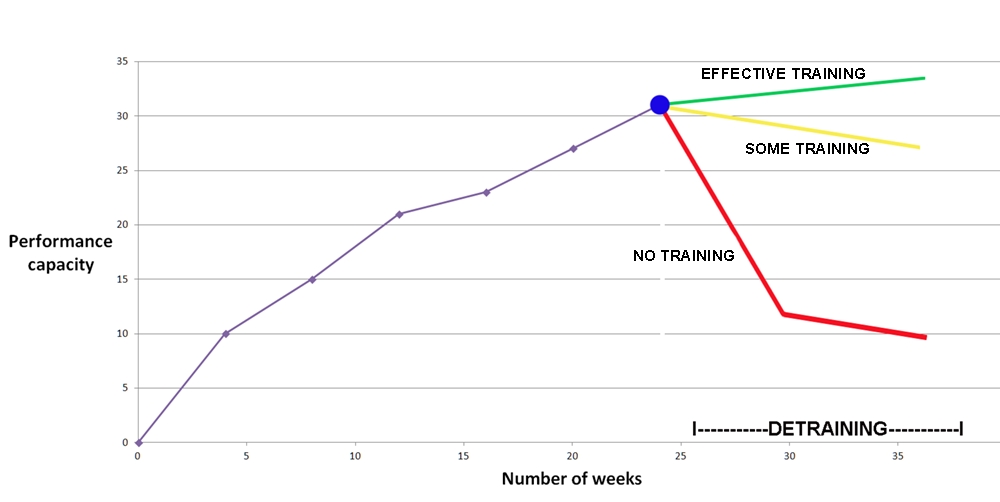

Alternative forms of exercise in the home can minimize the effects of detraining (see figure 1). Youths should be encouraged to maintain the World Health Organization’s recommendation of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each day. However, with varying socioeconomic situations, the amount of lockdown training amongst children can differ. Youth sports organizers should assess what participants were able to do in lockdown as a starting point for the reintroduction of formalized activity.

Figure 1 – Effects of training/detraining on physical capacity

A phased plan for the safe reintroduction to youth sports

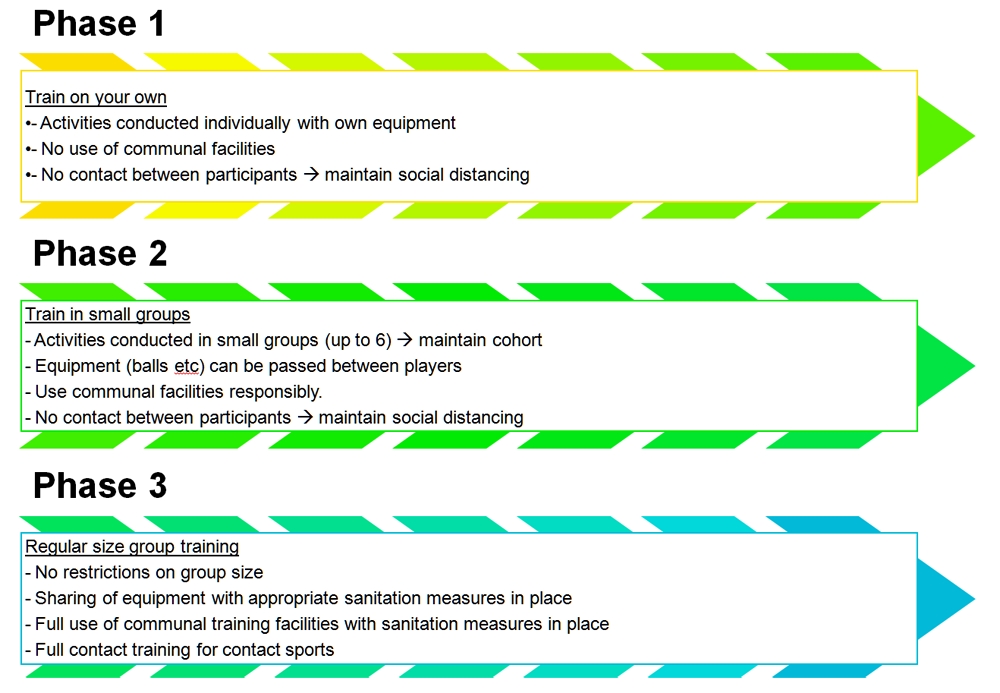

Worldwide, the majority of governments are adopting a phased approach to resume regular activity after periods of self-isolation and lockdown. The regulations and freedoms allowed at each stage differ from country to country. However, there are some general principles to follow when reintroducing activity in the sports arena (see figure 2). Adapt these to your governing body’s guidelines to return young people to sport safely.Figure 2 – A phased approach for return to sports participation.

Phase 1 – Train on your own

Kids probably maintained some level of physical activity during the lockdown. While younger children likely ‘played’, older youth without a gym undoubtedly performed bodyweight conditioning circuits. While effective at building strength, these types of workouts are not a substitute for the kind of neuromuscular training required to mitigate the injury risk presented by the reactive movement requirements of team sports(6).

It is essential to recognize that children's and adults' motivations to complete this type of in-home training are quite different. Youth are without many of the key drivers of youth sports participation (positive coaching, learning and improving, game participation, social interaction, and team rituals) during the ‘train on your own’ phase. As a result, the motivation to engage in solo training activities may falter.

Increase the motivation to engage in solo training by providing skill-development type activities that are engaging - as opposed to the typical exercise circuits. For example, challenge younger athletes to learn jump rope skills (two-foot, one foot, alternating feet, crossovers, double-under, etc.). Learning and progressing a new skill is inherently engaging for youngsters, while the plyometric nature of this task also provides a powerful stimulus against detraining. Motivate youngsters further by offering opportunities for social interaction - eg through video conferencing technology, posting videos of the tasks on digital team forums, or fabricating a competition amongst teammates or another team.

Phase 2 – Train in small groups

Despite the best intentions during phase 1, youth sports organizers should assume that participants have done little, if any, practical training during the lockdown period and gradually reintroduce more high-intensity types of movement. Kids likely missed reactive games where they must move appropriately in response to their opponent (action response coupling). Therefore, a good departure point for training is introducing small-sided games (1vs.1, 2vs.2, and 3vs.3 etc).

In the early phases of return to sport, maintain the same small groups for activities. This consistency limits the opportunity for viral infections across the whole group – a process known as cohorting. Initially, limit the field size in small-sided games as this allows participants to reacquaint themselves with jumping, stopping, turning, and accelerating skills at lower speeds. Progressively expand participant numbers and field size to increase game speed and intensify movement patterns. The bonus of introducing training in this manner is that small-sided games are highly engaging, making this phase of return to sport delightful for participants after a long period in isolation.

Phase 3 – Regular size training

When societies reach this phase, life will look more normal. Schools will be operating at full capacity, and it may be possible to resume competitive events. The injury risk concern during this phase will be the time frame since participants could engage in the full version of their sport. Therefore, they are likely to fatigue quickly from a reduced level of fitness. Fatigue decreases neuromuscular coordination and increases the likelihood of injury. Gradually increase early practice and match durations to avoid excessive levels of fatigue. Similarly, slowly progress total weekly training volume, at a rate of around 10% per week(9).

Take home message

Youth athletes and the sports they play differ from that of adults in many ways. A ‘one size fits all’ approach will not get the best outcomes for this subset of the sports community. Recognizing the practical and motivational challenges for youth sports participants during the pandemic will help organizers return children to sport safely while maintaining their long-term love for the game.References

- ESPN. 2013 Jul; www.espn.com/espn/story/_/id/9469252/hidden-demographics-youth-sports-espn-magazine

- BMC public health. 2016 Aug; 16(1) Article #752

- Ewing, M.E., & Seefeldt, (1996). Participation and attrition patterns in American agency-sponsored youth sports. In F.L. Small, & R.E. Smith (Eds.), Children and youth in sports: A biopsychosocial perspective, (pp. 31-46). Dubuque, IA: Brown and Benchmark

- The Aspen Institute. Accessed 2020 May; www.aspenprojectplay.org/youth-sports-facts/benefits

- Pediatrics. 2020 Apr; doi: doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702

- Br J Sports Med. 2015; 49(13):865-870

- European J Sport Sci. 2020 May: doi: doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1761076

- J Phys Act Health. 2015 Mar; 12(3): 424–433.

- Br J Sports Med. 2016 Sep; 50(17): 1043–1052

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.