You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Illiotibial band syndrome: compression or friction?

In the first part of this two-part article, Alicia Filley looks at new research on the underlying biomechanics of illiotibial band syndrome.

Up to 15% of all runners complain of point-specific tenderness at the lateral knee(1). The source of this pain is most often illiotibial band syndrome (ITBS), which also accounts for nearly 25% of all overuse injury complaints by cyclists(2). Most experts agree that an inflammatory process is at the root of the pain, but they debate the mechanism of injury.

Structure and function

The illiotibial band (ITB) is a fascial structure that courses along the lateral thigh (see figure 1). It arises from the iliac crest of the pelvis as a thickened extension of the fasciae latae, and forms the lateral fascial covering over the vastus lateralis. Proximally, fibres from the superior gluteus maximus and the tensor facia latae insert into the ITB near the region of the greater trochanter of the femur. Collagen fibres, arranged longitudinally along the line of force, give the ITB strength while elastin proteins scattered throughout give it some elasticity.

Figure 1: Anatomy of the illiotibial band as it courses the lateral thigh

The ITB arises superiorly from the iliac crest, merges with fibres from the tensor fasciae latae anteriorly and the gluteus maximus posteriorly, forms the fascial sheath for the vastus lateralis, and inserts distally on the patella and lateral tibial condyle.

Distally, the ITB splits into two insertions - one at the patella which functions as a tendon, and one that crosses the knee joint and attaches to Gerdy’s tubercle on the proximal tibial epicondyle, functioning as a ligament. Cadaver studies show that the ITB is continuous with the lateral intermuscular septum - the fascial separation between the anterior and posterior muscular compartments of the thigh - and firmly attaches to the linea aspera, a bony ridge along the posterior femur. Dissection also reveals that strong fibrous strands fan out from the ITB and attach to the area just proximal to the lateral femoral condyle (LFE), which is exactly where most athletes feel pain (see figure 2). The LFE appears covered with a thickened and fibrous periosteum and some strands of the ITB penetrate it to attach directly to the bone.

Figure 2: Sagittal view of the lateral side of the left knee

The tendinous portion of the ITB fans over the LFE on its way to the attachment on the patella. The ligamentous portion continues further to attach at Gerdy’s tubercle. Conflicting hypotheses attribute lateral knee pain to the rubbing of the fibres against the LFE, or the compression of the underlying fatty tissue or synovial outcropping(3).

Rubbed the wrong way

Clearly, the ITB is a well-anchored structure with minimal potential for movement. How then, is ITBS considered a friction syndrome? In the friction model, the posterior fibres of the ITB are thought to move in an anterior to posterior direction over the LFE as the knee flexes. The rubbing most likely occurs at around 30° of flexion. The hypothesis holds that even though the ITB is tightly bound to the femur and tibia with little apparent room for motion, tibial internal rotation and concurrent bowing of the vastus lateralis and biceps femoris, contribute to the tensioning of the ITB as the knee bends This therefore creates relative movement of the ITB in relation to the femur. Theoretically, the friction causes irritation of the LFE with resulting pain.

Using a sonogram to evaluate the motion of the ITB as the knee flexed in both supine and standing, researchers at the Mayo Clinic discovered that the distance between the anterior fibres of the ITB and the LFE decreases as the knee moves from full extension to 45 degrees of flexion(4). Scientists at Cardiff University also observed this movement of the ITB relative to the position of the LFE by observing knee flexion in a live model(5). The tension appeared to shift from the anterior to the posterior fibres of the ITB but there was doubt as to whether the entire band rubbed over the LFE.

This is why other researchers postulate that this movement is merely an illusion as the ITB repeatedly tightens(6). With flexion, the patella moves along the femoral condyle and the tibia moves posteriorly. This tightens the ligamentous part of the ITB – ie the portion that attaches to Gerdy’s tubercle on the tibia and stretches the posterior fibres of the ITB tautly over the LFE (see figure 2). Evidence via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show that this tightening produces compression rather than friction in the area (see figure 3). Magnetic resonance imaging shows that compression against the LFE is greatest at 30 degrees of knee flexion(5).

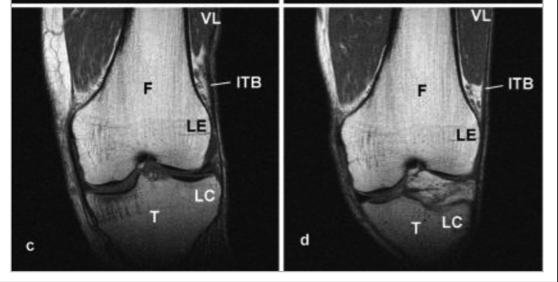

Figure 3: Representation of coronal view of the left femur (F) and tibia (T) in extension (left) and 30 degrees of flexion (right) as obtained from MRI

In extension, the ITB slopes laterally away from the lateral epicondyle (LE) of the femur to the lateral condyle (LC) of the tibia. With flexion, the ITB is pulled medially toward the LC and closer to the LE, compressing the fatty tissue or synovial outcropping that lies underneath(4).

Neither cadaver nor MRI investigations identified a bursa under the fibres of the ITB, despite the long standing belief that bursitis caused the pain of ITBS. Rather, a vascularised area of adipose tissue lies under the ITB at the LFE. This adipose tissue, filled with Pacinian corpuscles and both myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibres, is thought to be the source of irritation. Theoretically, this highly innervated tissue, when compressed, becomes inflamed and painful.

An investigation at Southwest Texas State University, however, showed a skeletal variation known as the synovial recess in patients who developed ITBS(7). This trough in the bone, seen primarily in the proximal tibia, extends beyond the joint line. In this trough, directly under the ITB, lies an out-pouching of the lateral synovial membrane, known as a ‘synovial fold’. Histologic evaluation of this tissue showed inflammation and hyperplasia, providing evidence of its role in the pain of ITBS(7).

Mechanism of injury

Regardless of whether the ITB rubs or compresses, repeated knee flexion results in lateral knee pain for many athletes. Researchers site both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons for this irritation (see table 1). Sports scientists at the University of Kentucky evaluated 34 males who ran on average 30km per week for differences in intrinsic kinematic function(8). Seventeen of the subjects exhibited ITBS and seventeen functioned as controls.

The group with ITBS showed significantly less flexibility in their ITBs, weaker hip external rotator strength, and greater hip internal rotation with knee adduction while running. However, only hip internal rotation and knee adduction exceeded the minimal detectable change score, (that smallest amount of change detected beyond what could be attributed to measurement error).

These were functional measurements, suggesting that the injured runners lacked neuromuscular control, perhaps due to their decreased external rotation strength, flexibility, or pain from injury. Since this was a retrospective study, it is impossible to know if these kinematic factors existed prior to symptoms of ITBS or not.

A prospective study at the University of Massachusetts measured strain, strain rate and the duration of impingement of the ITB of seventeen females who ran more than twenty miles per week and developed ITBS(9). After collecting 3-dimensional lower extremity kinematic data while running, computer software constructed an individual model of each subject. From these models, researchers calculated the strain and rate of strain of the ITB, and the range of knee flexion angles where the ITB would most likely interact with the LFE. This range of knee flexion where irritation could occur was termed ‘the duration of impingement’.

Being a prospective study, the subjects were uninjured during the data collection. After a diagnosis of ITBS, researchers compared their results to seventeen uninjured matched controls from the study. The results showed no significant differences for either the amount of strain or the angles of impingement between the control subjects and those who went on to develop ITBS.

Evaluation of the rate of strain, however, revealed a significant difference between the injured and control limbs, as well as the injured and uninjured limbs within the ITBS group. Looking at factors that would affect strain rate, data from this same study demonstrated a weak relationship between strain rate and hip adduction and knee internal rotation during running(9). This again points toward a lack of neuromuscular control while running, this time evidenced prior to symptoms of injury.

Other intrinsic factors associated with ITBS include varus knee alignment, (found in 33-55% of runners with ITBS), and leg length discrepancy (reported in 10-13% of ITBS cases)(10). Runners with ITBS also exhibit decreased hip abductor strength and decreased ITB flexibility when compared to controls(10). Extrinsic factors identified as causes for ITBS are poor fitting or old running shoes, poor cycle fit, training errors (such as rapid increases in mileage or hill training), and repeated running on an uneven surface. Some researchers hypothesise that intrinsic factors must also be present for extrinsic factors to cause symptoms(10).

| Intrinsic Factors | Extrinsic Factors |

|---|---|

| Decreased hip muscle strength, particularly the gluteal muscles | Rapid increase in mileage |

| Muscle imbalace between the anterior and posterior hip muscles | Hill training |

| Decreased neuromuscular control with resulting impaired muscle recruitment | Running on an uneven or slanted surface |

| Decreased range of motion at the hip | Old or ill-fitting running shoes |

| Decreased flexibility in the ITB | Poor cycle fit |

Biomechanical considerations

During the stance phase of running, one leg bears the entire load of the body weight, the ground reaction forces, and the eccentric burden of deceleration. In normal single-limb stance, the ground reaction forces pass medially to the knee, producing a varus force at the knee. When the hip adducts excessively due to skeletal abnormality, joint capsule tightness, muscle weakness, or medial foot placement, the force vector moves even more medially. This places a greater varus torque on the knee and stretches the lateral hip musculature, translating to more stress on the ITB (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Placement of ground reaction forces in the frontal plane during single limb stance

The arrow shows the ground reaction force medial to the knee joint. With hip adduction and a narrower base of support, the ground reaction force moves even more medially, placing a varus torque at the knee, stressing the lateral side.

As per the work of Vladimir Janda MD, this movement pattern of hip adduction and knee internal rotation identified in runners with ITBS can be attributed to muscle imbalances. According to Dr. Janda, muscles either act as tonic flexors or phasic extensors(11). The tonic muscles, of which the tensor fasciae latae is one, tend to become shortened and strong. Shortening of the tensor fasciae latae results in increased hip flexion and internal rotation.

The phasic extensor muscles of the hip include the gluteus medius and maximus. Phasic muscles are prone to weakness, inhibition, and lengthening. Therefore, the tonic tensor fasciae latae may override the phasic glutes and result in a postural pattern of movement that resembles a Trendelenburg sign, with increased hip adduction and knee internal rotation or varus. Athletes with ITBS consistently display this pattern of movement.

Conclusion

We’ve learned that ITBS, a common cause of lateral knee pain in runners and cyclists, is caused by repetitive knee flexion. Repeated flexion produces friction of the ITB along the LFE or compression that irritates the underlying fatty tissue or synovial out-pouching. The point in the movement arc where the ITB comes closest to the LFE appears to be around 30 degrees of knee flexion. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors contribute to ITBS.

Runners who suffer with ITBS typically show an altered movement pattern of hip adduction and knee internal rotation on the affected side. This pattern of movement showed an association with a significantly increased rate of strain on the ITB in athletes who, after evaluation, went on to develop ITBS. In the next instalment, we will explore which treatment options most effectively influence this pattern of movement and relieve the pain of ITBS.

References

- Sports Med. 2012;42(11):1-24

- Manual Therapy. 2007;12:200-208

- Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016;27:53-77

- J Ultrasound Med. 2013 Jul;32(7):1199-206

- J Anat. 2006 Mar; 208(3): 309–316

- Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2010;3:18-22

- 1996 Oct;12(5):574-80

- J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014 March;44(3):217-222

- Clinical Biomechanics. 2008;23:1018-25

- 2011;3:550-561

- jandaapproach.com

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.