You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Chronic Pain Management: Long-Term Relief

Chronic pain is a significant challenge for athletes, often persisting beyond the injury healing period and affecting their performance, daily life, and mental well-being. Carl Bescoby explores the complexities of chronic pain in athletes, emphasizing the limitations of traditional physical treatments and the importance of a biopsychosocial approach.

Atlanta Hawks forward Jalen Johnson is defended by Dallas Mavericks center Daniel Gafford in the fourth quarter at State Farm Arena. Mandatory Credit: Brett Davis-Imagn Images

Chronic pain is a persistent issue that practitioners regularly encounter in athletes. Unlike acute injuries, where physical treatment and rest often lead to recovery, chronic pain frequently remains unresolved despite conventional physical interventions and treatment options. This pain can last for months or even years, reducing the athlete’s ability to perform, train, or engage in daily activities. For athletes, managing this kind of pain becomes more complicated because they are often conditioned to push through pain to succeed, which can exacerbate the problem. The failure of purely physical interventions highlights the need for alternative approaches. Integrating psychological principles into physical rehabilitation offers a holistic approach that considers the interplay between mind, body, and environment in achieving long-term relief.

Pain and Central Sensitization

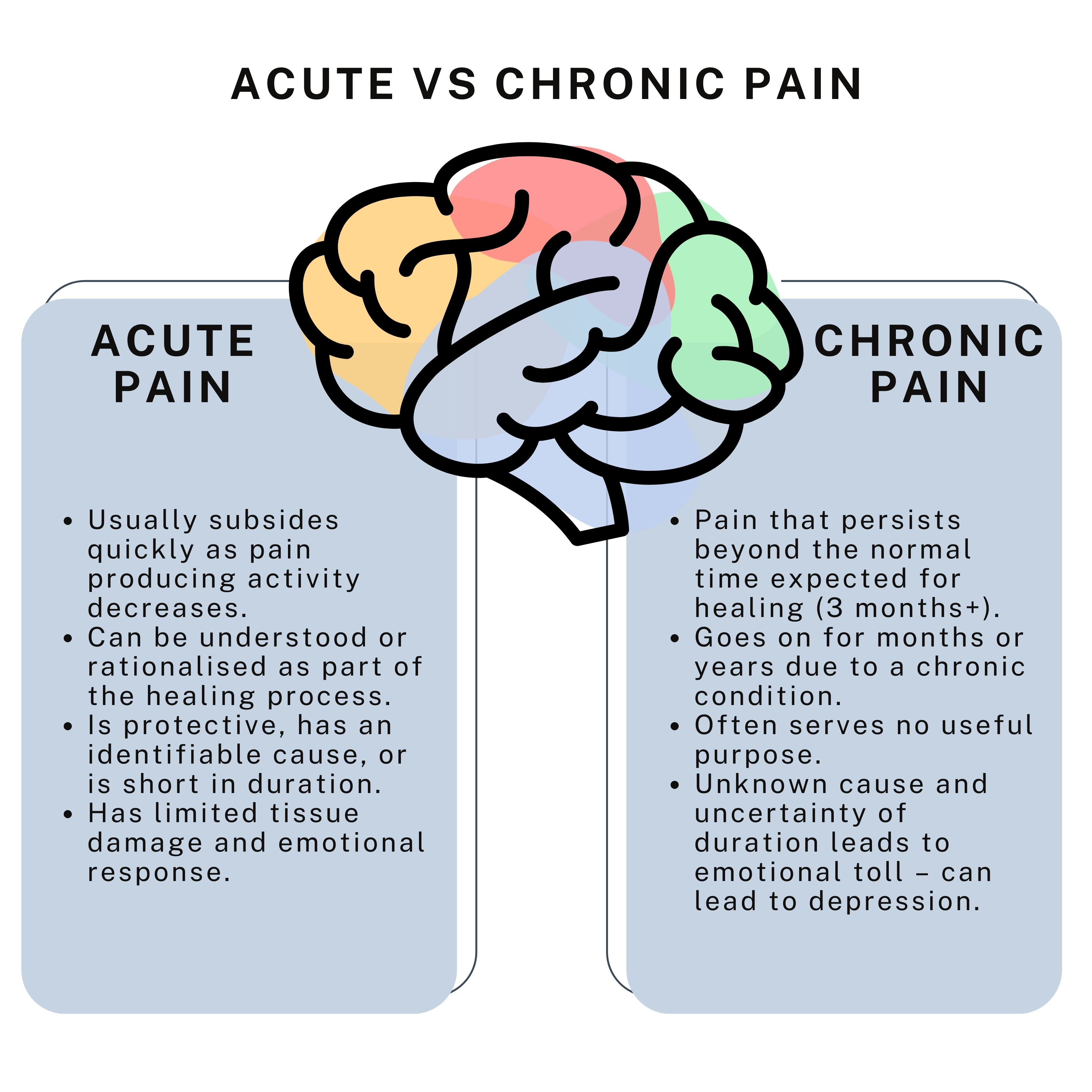

Acute pain is typically short-term and serves as a protective response to injury, alerting the body to tissue damage and initiating healing processes. It usually resolves as the injury heals. Chronic pain lasts for an extended period (often beyond the normal healing time) and can persist even after the initial injury has healed (see figure 1)(1). Chronic pain results from changes in how the brain and nervous system process pain signals. Over time, the brain may become hypersensitive, interpreting normal sensations or minor discomfort as severe pain(2,3). For athletes, this can lead to psychosocial challenges, as traditional rest or physical treatment approaches fail to alleviate the pain(4).

“To make complex pain mechanisms more accessible, it’s important to use metaphors and analogies…”

Central sensitization refers to the process by which the central nervous system (CNS) becomes sensitized to pain, amplifying pain signals beyond their original intensity(5). This occurs when neurons in the spinal cord and brain undergo changes that increase the body’s sensitivity to stimuli, even when the original injury is healed. In athletes with chronic pain, the CNS can continue to send pain signals even without ongoing tissue damage, causing them to experience pain during normal movements or activities. This phenomenon complicates rehabilitation because standard treatments like physical therapy or pain medication target the site of pain, rather than addressing the nervous system’s role in amplifying it(5).

Psychologically Informed Approach

Pain science suggests that chronic pain is influenced by tissue damage and how the brain processes pain signals. Psychological factors, including stress, fear, and negative emotions, can worsen the pain experience. A psychologically informed approach, which integrates mental and emotional health into rehabilitation, offers a more effective solution for managing chronic pain in athletes(6). By addressing these psychological elements, practitioners can help athletes reduce pain, enhance recovery, and improve overall performance. Three core psychological factors that influence the management of chronic pain include pain catastrophizing, fear avoidance behavior, and the emotional toll on athletic identity. Pain catastrophizing occurs when athletes become overly focused on their pain and anticipate the worst possible outcomes. They may believe the pain will never improve, or they fear that any movement will lead to further injury. This mindset amplifies the pain experience and can lead to increased emotional distress. Pain catastrophizing is a significant predictor of disability and prolonged recovery in athletes.

Secondly, athletes with chronic pain often develop a fear of movement, believing that physical activity will worsen their condition. This fear leads to avoidance of activity, known as fear avoidance behavior, which can result in muscle deconditioning, decreased mobility, and heightened pain sensitivity. Over time, this cycle of fear and avoidance reduces the athlete’s ability to engage in sports or even daily functions, contributing to long-term disability. Third, chronic pain not only impacts physical performance but also takes a heavy emotional toll on athletes. Many athletes derive their sense of identity and self-worth from their ability to perform at a high level. Persistent pain threatens this identity, leading to feelings of anxiety, depression, and frustration. Athletes may feel isolated, as they are unable to train or compete alongside their peers, further impacting their mental health and prolonging their recovery(6).

Long-Term Chronic Pain Management

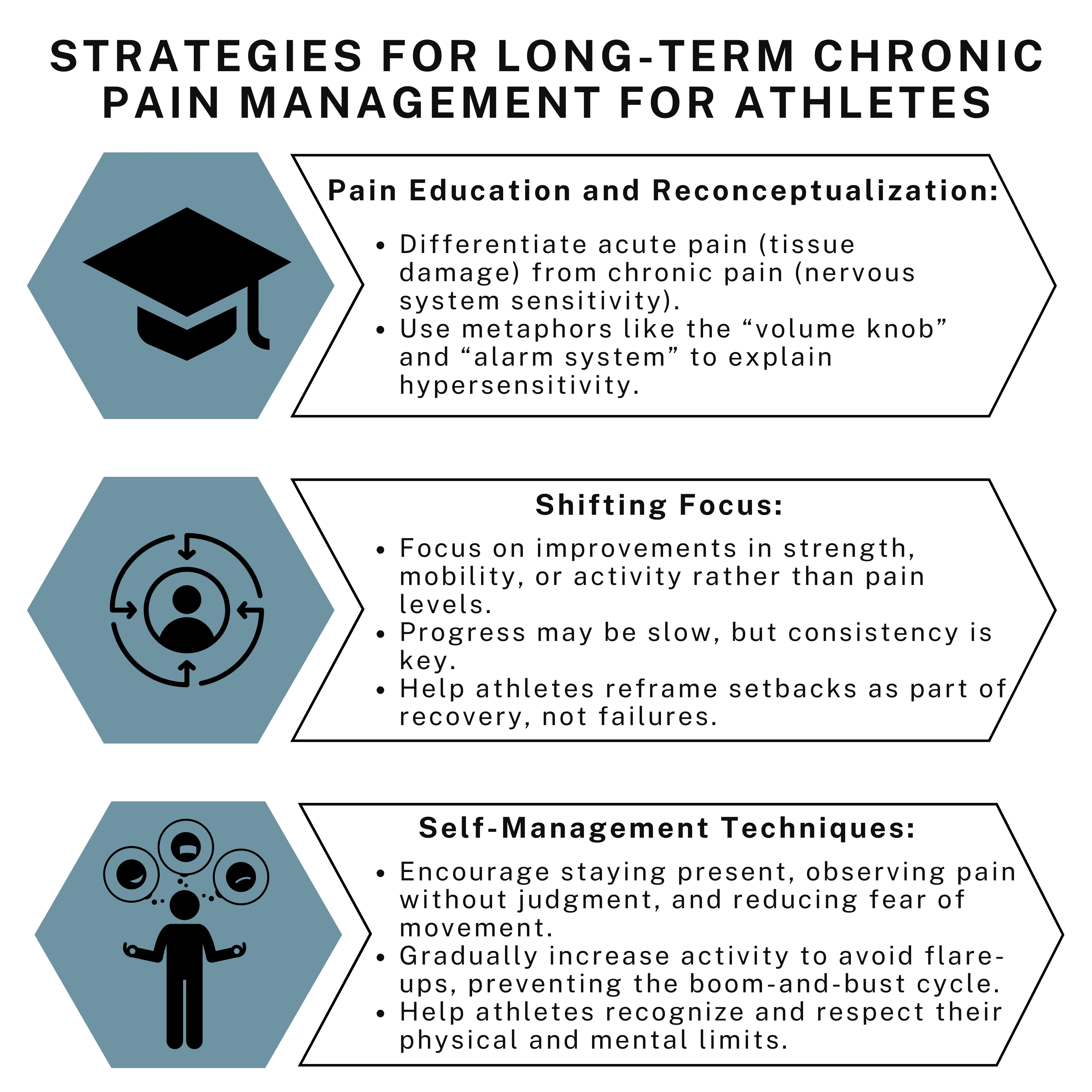

The long-term strategies for chronic pain management include pain education and reconceptualization. Education is the foundation that helps athletes shift their focus and encourages self-management techniques (see figure 2).

Pain education and reconceptualization

One of the most important aspects of managing chronic pain in athletes is helping them understand how pain works(7). For athletes, pain is often seen as a clear indicator of injury or harm, especially in the context of acute injuries, where pain typically reflects tissue damage. However, chronic pain is different. It persists long after the tissue has healed, and it often does not correspond directly to physical damage. Practitioners need to help athletes differentiate between acute pain, a protective mechanism alerting them to injury, and chronic pain, a maladaptive response where the nervous system becomes overly sensitive. By educating athletes on this distinction, you can help them begin to see their pain not as a sign of ongoing harm but as a complex interplay between their brain and body.

Athletes dealing with chronic pain often have misconceptions about what their pain means(8). They may believe that persistent pain indicates ongoing injury or that any movement will lead to further damage. These beliefs contribute to fear, avoidance of activity, and emotional distress, all of which can exacerbate the pain experience. Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) helps debunk these myths, reassuring athletes that pain does not always mean damage. This understanding is crucial for reducing fear and anxiety about movement, empowering athletes to re-engage with physical activity in a measured and safe way. For example, explaining that chronic pain is often the result of the nervous system becoming hypersensitive, sending pain signals even when there is no immediate threat to the body.

“…this approach supports sustainable recovery and enhances overall well-being.”

To make complex pain mechanisms more accessible, it’s important to use metaphors and analogies that resonate with athletes. One effective analogy is the “volume knob” for central sensitization. Explaining to athletes that with chronic pain, the nervous system acts like a volume knob that has been turned up too high—normal sensations that should not cause pain are amplified by the brain. This metaphor helps athletes visualize how the nervous system can become overly reactive, even without a new injury. Another common analogy is comparing pain to an “alarm system” that has become overly sensitive, where the alarm goes off even when there’s no real danger. These simple explanations can foster greater understanding and reduce the fear associated with chronic pain, helping athletes trust the rehabilitation process and regain confidence in their bodies. Through education, athletes can learn that while pain is real, it is not always a direct reflection of tissue damage, and by addressing both the physical and psychological aspects of their pain, they can move forward toward recovery.

Shifting focus

When working with athletes experiencing chronic pain, one of the key strategies is to shift their focus away from pain as the primary indicator of progress(7). Athletes often measure their recovery based on how much or how little pain they feel, which can lead to frustration if pain persists despite treatment. Instead, practitioners can help athletes redirect their attention to functional improvements. This means focusing on what they can do rather than how much pain they are in. Functional goals—such as increased mobility, improved strength, or the ability to engage in specific activities—become the new benchmarks for progress. By emphasizing function over pain, athletes can begin to see tangible signs of improvement, even if pain fluctuates. This shift in mindset reduces the psychological grip of pain and encourages a more positive and proactive approach to rehabilitation. For example, an athlete might still feel some discomfort but notice that they are able to run for longer periods, perform a lift with better form, or increase their range of motion. These functional gains demonstrate that they are on the path to recovery, even if pain has not fully resolved.

“Pacing is essential for athletes to avoid pushing themselves too hard and triggering pain flare-ups.”

Managing chronic pain is a long-term process, and it’s important to set realistic expectations with athletes early on. Many athletes expect quick fixes, particularly when they are used to overcoming acute injuries through rest and targeted treatment. However, chronic pain recovery is different—it often requires a more gradual, step-by-step approach. Helping athletes understand that progress may be slow but steady can prevent feelings of disappointment and discouragement. Athletes need to know that it is normal for pain to persist, fluctuate, or even spike temporarily during the recovery process. Rather than viewing these as setbacks, they can be reframed as part of the natural course of healing.

Self-management techniques

A crucial aspect of supporting athletes with chronic pain is empowering them to manage their symptoms independently(8). By teaching self-management techniques, practitioners can help athletes develop skills to maintain long-term control over their pain and function(9). These techniques include mindfulness, pacing, and understanding training limits. Mindfulness practices can help athletes stay present and reduce the emotional and cognitive reactivity that often exacerbates pain(10). Teaching athletes to observe their pain non-judgmentally, without catastrophizing or fearing it, allows them to manage discomfort more effectively. Mindfulness also enhances their awareness of their body’s limits and responses during training, which can prevent over-exertion and flare-ups.

Pacing is essential for athletes to avoid pushing themselves too hard and triggering pain flare-ups(11). Athletes often struggle with overdoing it during good days or avoiding activity altogether due to fear of pain. Pacing helps them find a middle ground, where they gradually increase activity while avoiding the boom-and-bust cycle of pain. By breaking activities into manageable portions and incorporating rest, athletes can build up their strength and endurance without overwhelming their system. Chronic pain often requires athletes to recalibrate how they approach their training. Teaching athletes to recognize their physical and mental limits is vital for long-term pain management. Encouraging athletes to respect their body’s signals, rather than ignoring or pushing through them, helps prevent reinjury or exacerbation of chronic pain. By fostering a mindset that balances ambition with self-care, athletes can maintain consistent progress in their recovery.

Conclusion

Managing chronic pain requires a holistic approach that goes beyond traditional physical treatments. By incorporating the biopsychosocial model, practitioners can address the physical aspects of pain and the psychological and social factors that contribute to its persistence. Pain education, reconceptualization, and a focus on functional progress help athletes understand the complexity of chronic pain and shift their mindset from fear and avoidance to active engagement in their recovery. Self-management techniques such as mindfulness, pacing, and understanding physical limits may empower athletes to take control of their pain, fostering resilience and long-term recovery. While chronic pain presents unique challenges, integrating psychological strategies into rehabilitation provides athletes with the tools they need to overcome pain and regain their confidence, function, and identity in both sports and daily life. Ultimately, this approach supports sustainable recovery and enhances overall well-being.

References

1. B J of Anaesthesia. 2010, 105 (1), i69–i85.

2. IASP Announces Revised Definition of Pain. Int Ass for the Study of Pain.

3. J of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2011, 19(4), 186–193.

4. Tel Chronic Pain Management for the Elite Athlete Population. 2023.

5. The J of pain. 2009, 10(9), 895-926.

6. The Clin J of Pain. 2021, 37(3), 219-225.

7. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2022, 17(6):981-983.

8. Myths and Misconceptions about Chronic Pain. 2002.

9. Pain Management. 2015, 6(1), 75–88.

10. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2024, 1-11.

11. Annals of Medicine. 2023, 55(2), 2270688.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.