You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Can You Isolate VMO During Exercise?

Practitioners understand the importance of restoring quadriceps strength following a knee injury. However, a common belief is that the VMO can be isolated during certain exercises. Eurico Marques uncovers the evidence and provides clinicians with pragmatic recommendations.

Pittsburgh Pirates designated hitter Andrew McCutchen (22) grabs his knee after falling to the ground to avoid an inside pitch. Mandatory Credit: Charles LeClaire-USA TODAY Sports

The vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) muscle, a part of the quadriceps muscle group, plays a crucial role in stabilizing the patella and ensuring proper knee function. The VMO is often a focal point in rehabilitation exercises to improve knee stability and address patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS). An imbalance between the VMO and the vastus lateralis (VL) contributes to the development of patellofemoral pain syndrome, and VMO atrophy or inhibition contributes to patellar instability(1). A prevalent belief in sports science and rehabilitation is that specific exercises, particularly knee extensions, can target and isolate the VMO(1). This narrative permeates common society, and it isn’t uncommon to hear athletes say, “I need to strengthen this muscle on the inside of my knee.”

Researchers use electromyography (EMG) to measure the activation levels of the VMO and VL muscles during exercises. They represent these measurements as a ratio (VMO/VL) to assess VMO activity, with a ratio greater than 1 indicating preferential VMO activation. Clinicians may alter hip, knee, ankle, or forefoot positions or co-contract lower extremity muscles to enhance VMO activity. However, it may not be possible to selectively strengthen the VMO(2,3,4).

Understanding the relationship between the vastus medialis weakness and patellar tracking is useful in diagnosing, treating, and preventing patellar subluxation and dislocation. Furthermore, the VMO is the first muscle to atrophy following knee injury(5).

VMO Anatomy and Function

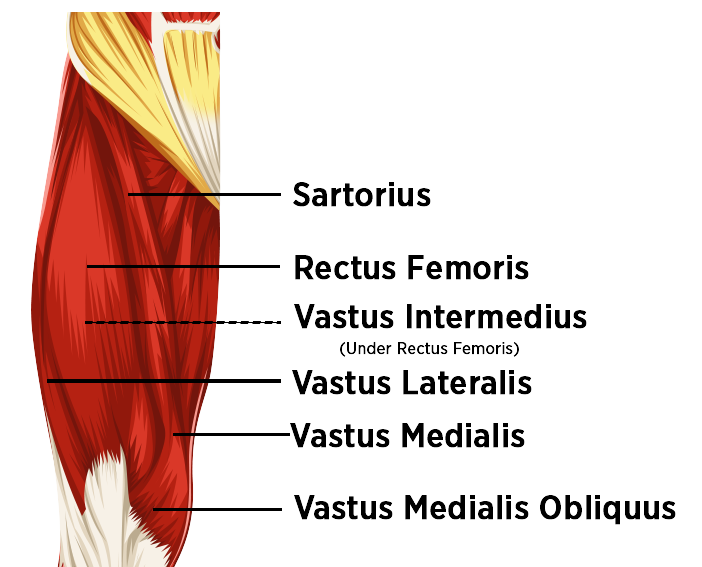

The VMO is the most distal and medial portion of the vastus medialis muscle, part of the quadriceps femoris group (see figure 1). Its oblique fibers are oriented at an angle to the femur, contributing to its unique role in knee mechanics. Based on a muscle fiber orientation, VMO is not primarily involved in knee joint extension and indirectly contributes to the knee extension torque(6).

The anatomical structure of the quadriceps muscle group further complicates the idea of isolating the VMO. The quadriceps muscles share a common neural innervation and tendon, the quadriceps tendon, which inserts into the patella. This shared neural and tendon structure means that any contraction of the quadriceps muscles will inherently involve some degree of coordinated activity across all components. Vastus medialis obliquus might contribute to generating the knee joint torque consistently through the range of motion. Therefore, facilitating the neural drive for VMO is important during rehabilitation(6).

The Concept of Muscle Isolation

Muscle isolation refers to activating a specific muscle independently of others during an exercise. In the context of the quadriceps, this means engaging the VMO without significantly activating other quadriceps muscles, such as the vastus lateralis, rectus femoris, or vastus intermedius. This concept is central to rehabilitation settings where targeting the VMO might be desired to correct imbalances or address specific patellar tracking issues(1). Now, while most practitioners can agree that there is no way to activate only one muscle, they continue to use “isolate” when discussing exercise prescriptions with athletes. While they may argue that it is simply semantics around “isolating” and “enhancing” activation, athletes and the general public may not be able to differentiate and apply these everyday words in the context of rehabilitation. They may create unhealthy thoughts around “weakness” and the etiology of their pain. It facilitates a biomedical approach to what is a complex biopsychosocial interplay.

Clinicians’ words can profoundly influence patients’ perceptions, potentially aiding or hindering their rehabilitation. Psychological factors, often overlooked in favor of biomedical ones, can more accurately predict pain and disability levels. Misunderstood medical terms can cause unnecessary fear, so clinicians must communicate clearly and reassuringly. A holistic approach, integrating both physical and psychological aspects of patient care, fosters better patient outcomes and helps them manage their conditions more effectively(7).

Can the VMO be Isolated?

Researchers at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital conducted a systematic review in 2009 to answer this question(1). The review included 387 subjects from 20 studies and found that altering lower limb joint orientation or co-contraction does not preferentially isolate VMO over VL (see table 1)(1). Three papers demonstrated that co-contraction may enhance VMO activation, but the researchers warrant caution due to limitations in the study design and reporting. The limitations include:

1. Gaps in the exact placement of the EMG electrodes, creating doubt on the data reliability,

2. Poorly described subject characteristics,

3. Poorly described participant inclusion methods,

4. Small sample sizes, and

5. Poor reporting of how pain influenced participants with PFPS. Pain influences muscle contraction and strength through arthrogenic muscle inhibition(8).

The authors conclude that physiotherapists should not attempt to focus primarily on the VMO. The anatomical and functional interconnectedness of the quadriceps muscles means that VMO weakness is more likely indicative of complete quadriceps weakness. Therefore, improving quadriceps strength will improve the function of all the muscles associated with knee extension and patellar stability.

Table 1: Summary of findings in systematic review(1)

| Study | Sample Size | Population Characteristics | Testing Procedure | EMG results |

| 1 | 16 | Asymptomatic | Isometric knee extension in standing with ankle dorsiflexion and femoral rotation | No preferential VMO activation |

| 2 | 20 | Asymptomatic | Various quadriceps exercises with and without co-contraction | No preferential VMO activation |

| 3 | 20 | Asymptomatic | Leg press with and without ankle eversion | No preferential VMO activation |

| 4 | 14 | Asymptomatic | Squats with and without hip adduction | No preferential VMO activation |

| 5 | 10 | Asymptomatic | Cycling with different foot positions | No preferential VMO activation |

| 6 | 43 | Asymptomatic | Step-ups with and without hip rotation | No preferential VMO activation |

| 7 | 8 | Asymptomatic | Single-leg squats with and without hip adduction | No preferential VMO activation |

| 8 | 10 | Asymptomatic | Straight leg raises with and without pelvic tilt | Co-contraction can enhance VMO activity |

| 9 | 12 | Asymptomatic | Leg press with different foot positions | No preferential VMO activation |

| 10 | 10 | Asymptomatic | Knee extension with and without hip adduction | No preferential VMO activation |

| 11 | 12 | Asymptomatic | Squats with different foot positions | No preferential VMO activation |

| 12 | 15 | Asymptomatic | Leg press with and without ankle inversion | Co-contraction can enhance VMO activity |

| 13 | 10 | Asymptomatic | Isometric knee extension with different hip rotations | No preferential VMO activation |

| 14 | 6 | Patellofemoral pain syndrome | Knee extensions with and without hip rotation | No preferential VMO activation |

| 15 | 8 | Asymptomatic | Leg press with different foot positions | No preferential VMO activation |

| 16 | 10 | Asymptomatic | Leg press with different foot positions | No preferential VMO activation |

| 17 | 11 | Asymptomatic | Leg press with and without co-contraction of gastrocnemius | Co-contraction can enhance VMO activity |

| 18 | 18 | Patellofemoral pain syndrome | Knee extensions with and without co-contraction | No preferential VMO activation |

| 19 | 18 | Patellofemoral pain syndrome | Leg press with and without foot inversion | No preferential VMO activation |

| 20 | 11 | Asymptomatic | Squats with different foot positions | No preferential VMO activation |

EMG Evidence

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) causes anterior or retro patellar pain and is prevalent in athletic and non-athletic populations. The incidence of PFPS is notably high, affecting about one in four individuals. Weakness in the VMO may contribute to PFPS, leading to treatments focused on strengthening the VMO. Researchers at the Grand Valley State University in the USA aimed to examine the activation of the VMO and VL muscles during rehabilitative exercises to determine effective treatment methods for PFPS(9).

They used EMG to measure the activation levels of the VMO and VL muscles during four rehabilitative exercises. The study examined the effects of different lower limb joint positions and muscle co-contractions on VMO activation to see if these variables could preferentially enhance VMO activity over VL. The exercises evaluated included open-chain knee extension and other lower extremity movements across various knee angles(9).

The findings revealed inconsistent results. While some exercises and specific joint positions showed potential for enhancing VMO activation, the results did not consistently support one method over another. The study highlighted the complexity of achieving selective VMO activation. The authors suggest that no single exercise or joint position could universally preferentially strengthen the VMO(9). Therefore, clinicians should be cautious in recommending particular rehabilitative movements solely for this purpose. Instead, a more comprehensive approach to strengthening the entire quadriceps complex may be necessary.

To further highlight the interconnectedness of the quadriceps complex, researchers at the University of São Paulo aimed to challenge the hypothesis that hip abduction for PFPS facilitates the vastus lateralis longus (VLL) muscle activation, leading to a VLL and VMO imbalance(10). The results showed no selective EMG activation occurred between the VMO, VLL, and VLO during the different exercises, indicating that hip abduction exercises may not exacerbate VMO and VL muscle imbalances in healthy individuals(10).

Practical Implications in Rehabilitation

Holistic Quadriceps Strengthening

- Focus on strengthening the entire quadriceps muscle group rather than attempting to isolate the VMO.

- Use exercises that engage all quadriceps muscles, such as squats, leg presses, and lunges, to improve overall knee stability and function.

Exercise Selection

- Avoid promising that specific exercises will isolate or preferentially strengthen the VMO.

- Incorporate a variety of exercises that promote balanced muscle activation.

- Use open-chain and closed-chain exercises at different knee angles to ensure comprehensive management.

Patient Communication

- Use clear, positive, and non-threatening language when discussing muscle activation and rehabilitation goals.

- Educate patients on the importance of overall quadriceps strength and its impact on knee health rather than focusing solely on the VMO.

Addressing Psychological Factors

- Consider psychological factors and their impact on pain and recovery.

- Adopt a biopsychosocial approach to rehabilitation.

- Ensure athletes understand that various factors beyond muscle strength alone influence knee pain and function.

Monitoring and Adaptation

- Regularly assess progress and adapt exercise programs.

- If available, use objective measures to monitor muscle strength.

Clinicians must base exercise prescriptions and rehabilitation strategies on current research and evidence rather than prevailing myths. Furthermore, they must be cautious about claims that specific positions or co-contractions can isolate the VMO, as evidence does not consistently support these methods.

Conclusion

Substantial evidence supports the hypothesis that the VMO cannot be isolated during knee extensions or any knee exercise. The anatomy and innervation of VMO means that it cannot be completely isolated from other quadriceps muscles. Practical implications for rehabilitation should focus on comprehensive quadriceps strengthening and neuromuscular training to enhance overall knee stability and function.

References

1. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 25(2):69–98, 2009

2. Physical Therapy, 75: 672–683

3. Physical Therapy in Sport 7: 87–92

4. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 11: 120–126

5. www.clinbiomech.com/article/S0268-0033(99)00089-3/abstract#articleInformation

6. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2020 Dec; 5(4): 98

7. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018;48(7):519–522

8. J Sport Rehabil. 2021 Sep 1;31(6):707-716

9. The Open Rehabilitation Journal, 2012, 5, 1-7

10. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2006, 3:13

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.