You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Back in the Game: A Criteria-Driven RTS Path

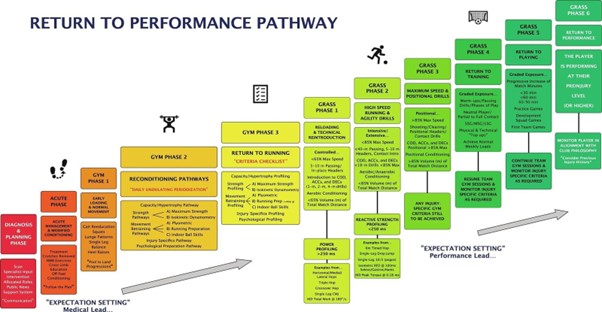

Return to performance pathways evolve as clinicians rethink and interpret existing protocols to meet their environments. Kelly MacKenzie discusses a criteria-driven return to sports pathway that can be adapted for all athletes, irrespective of their sport and level

Inter Miami CF defender Ian Fray leaves the pitch with an injury during the second half against Atlanta United in a 2024 MLS Cup Playoffs Round One match at Chase Stadium. Mandatory Credit: Sam Navarro-Imagn Image

An effective, user-friendly, cost-efficient, and reproducible return to play protocol is crucial for athletes across all sports and skill levels to ensure they regain or surpass their previous performance while reducing re-injury risk. While extensive research has been conducted in recent years, much of it focuses on performance rather than on providing optimal support for the athlete.

Andrew Mitchell, a sports physiotherapist and strength and conditioning coach with extensive experience working with professional athletes and English Premier League teams, recently discussed a new protocol from his latest paper on the JOSPT podcast. The protocol expands the control chaos continuum by creating an 11-phase framework with clear progressions and objective criteria to guide decision-making at each stage(1).

The new protocol is user-friendly and allows different individuals to handle separate phases. The objective, data-driven, step-by-step approach should improve athlete engagement and compliance. Apps and self-measured testing make it unnecessary to invest in costly tools. Key terms in the protocol further break down return to play into four phases, providing clear expectations for all involved: return to running, return to training, return to play/practice, and return to performance(1).

“Clinicians must use precise terminology and effectively communicate the criteria…”

Meeting the criteria in the early phases is crucial to prevent setbacks and frustration in later stages. Athletes must meet the clinical, physical, and psychological criteria before progressing through each phase (see table 1)(1).

Table 1: The supplementary clinical, physical, and psychological progression criteria

| Clinical | Physical | Psychological |

| No increase in pain specific to the injury (no more than 2-4/10 on a visual pain scale). | Must demonstrate competent movement skills. | Must not experience fear or anxiety. |

| No increase in pain specific to the injury (no more than 2-4/10 on a visual pain scale). | Visual assessment confirms no balance loss, contralateral hip drop, knee valgus (same side), or excessive trunk movement. | Use a global scale from 0-100% daily, with 0% indicating no ability to progress and 100% showing full confidence to proceed. |

1. Diagnosis and planning phase

After clinicians assess and diagnose the athlete, the multidisciplinary team will discuss and create a practical, criteria-based plan. This ensures everyone, including the athlete, understands the plan and expectations. Emotional and psychological support involving family, friends, peers, and other practitioners is crucial in the early days to build trust and understanding(2).

2. Acute phase – Acute management and modified conditioning

Treatment starts with pain relief using various physiotherapy techniques such as massage, cryotherapy, or neuromuscular stimulation. Early exercises focus on improving range of motion and neuromuscular control while minimizing muscle atrophy. The injury is closely monitored for swelling or pain (<4 on the VAS), which could signal overexertion. Once the athlete is comfortable, modified conditioning begins, with exercises planned to protect the injury while maintaining fitness. The level and duration of protection depend on the injury’s severity. Training the uninjured limb through strength, balance, and plyometrics can aid recovery and maintain overall fitness(3).

3. Gym phase one – Early loading and normal movement

In this phase, training occurs in the pool, gym, or transitions from pool to land. Early gym-based rehabilitation keeps the athlete engaged in the team environment. The injury is loaded early, focusing on fundamental and initial movement patterns. These basic movements (squats, step-ups, lunges, heel raises, bridging, and single-leg balance exercises), including components of the gait cycle, may aid in gait re-education. The athlete moves to the second gym phase once they demonstrate good, pain-free mastery of these fundamentals(4).

4. Gym phase two – Reconditioning

Clinicians shift the focus to reconditioning pathways and progress multiple themes systematically based on each injury’s healing time. Key themes include capacity/hypertrophy, strength profiling (maximum strength and isokinetic testing), movement retraining (plyometrics, running prep, ball skills), injury-specific, and psychological preparation. Athletes with mild injuries may complete multiple steps in one session if confident, while severe injuries may require days or weeks to progress(1).

5. Gym phase three – Return to running

As athletes improve, clinicians must initiate a return to running protocol. They must use objective measures and a specific checklist to ensure athletes have the necessary capacity (see table 2). Clinicians can start athletes on the grass to minimize the impact forces and integrate sports-specific skills. They must use the Performance Symmetry Index (PSI), a metric that evaluates recovery and readiness, to objectify their decision-making. The PSI aims to restore the athlete’s performance to pre-injury levels, preseason benchmarks, or previous data from regular limb monitoring. If no data is available, clinicians can use comparable cases or limb symmetry, with careful interpretation to account for deconditioning or improvements during rehab. The analysis must be individualized, and the clinical criteria and performance goals must be considered(1).

Table 2: Objective measures and checklist for return to running(1)*

| Profiling & Assessment Criteria |

| Capacity/Hypertrophy: |

| Exit: ≥100% PSI |

| 1. SL squat: 25 |

| 2. SL 90° hamstring bridge: 30 |

| 3. SL 30° hamstring bridge: 30 |

| 4. SL straight leg heel raise: 35 |

| 5. SL knee-flexed heel raise: 35 |

| Strength: |

| Maximum strength, >90% PSI |

| 1. Anterior chain (SL press): 1.5x BW |

| 2. Posterior chain (Nordic): 425N |

| 3. Calf complex (SL heel raise): 80% BW |

| Strength (IKD): |

| 3-speed profiling, >90% PSI |

| 1. 5 reps at 60°/s: quads PT (3x BW) |

| 2. 10 reps at 180°/s: hamstrings PT (1.8x BW) |

| 3. 15 reps at 300°/s: total quad/ham work |

| Movement Retraining: |

| Plyometric, >80% PSI |

| 1. SL hop series |

| 2. SL crossover hop (intro) |

| 3. SL 6m timed hop (intro) |

| Forceplate Jumps: |

| 80% PSI |

| DL/SL CMJ, DL drop jumps, 10/5 pogos |

| Technical Running Preparation: |

| Exit: Session completion |

| Running prep: "1000 ground contacts" |

| Mechanics: A skips, B skips, heel flicks, etc. |

| Running Preparation (Antigravity Treadmill): |

| Exit: Session completion |

| 2-min intervals @ 40% peak speed, 5 sets (15 min total), 95% BW |

| Hop Drills & Ball Skills: |

| Exit: Session completion |

| Tegball game |

| Injury Specific: |

| Tailored per injury |

| SL isometric hamstring profiling, hop stabilization, outlier exercises |

| Psychological: |

| 80% readiness/confidence on global scale |

*Clinicians must use their tools to balance physical, clinical, and psychological criteria. This varies depending on their available resources, but innovative and simple solutions do exist to aid when resources are limited.

6. Grass phase one – Reloading and technical reintroduction

Reloading and technical reintroduction should take place on grass, a low-impact surface. The focus is on aerobic fitness and power through low-intensity linear running with high control. Clinicians may include skills-based activities like dribbling and short passes. A key element of grass phase one is power profiling, using tests like the hop battery and single-leg countermovement jump, measured with the PSI. These exercises, performed before or after the grass session, help improve ground contact times (GCT). The athlete must meet objective power metrics before advancing to grass phase two(5).

7. Grass phase two – High-speed running and agility drills

Intensive and extensive volume-based sessions help gradually increase the load and prevent training spikes as the athlete returns to team training. High-speed running (<85% max speed) and agility drills, including acceleration, deceleration, and reactive decision-making, prepare them for position-specific drills in grass phase three. Drills start at 4m and progress to 18m to raise intensity while passing and heading distances also gradually increase(6).

Athletes participate in extensive sessions on separate days, covering no more than 85% of the total match distance. In cases where this information is unavailable (i.e., amateur athletes), clinicians can use population norms. Furthermore, clinicians must emphasize gym-based reactive strength profiling using tests like the 6m timed hop and single-leg drop jumps, focusing on PSI and improving GCT. For example, clinicians can use isokinetic calf, quad, and hamstring testing for lower limb injuries, if available.

Meeting these metrics with quality movement patterns and athlete confidence is crucial before progressing. When exact data is unavailable, the MDT must collaborate to determine acceptable standards.

8. Grass phase three – Maximum speed and positional drills

Clinicians can now incorporate maximum speed (>85% max) and high-intensity positional exercises. The drills become more chaotic with added variables like other players, increasing cognitive load, and building confidence. For example, in football, this may include proficiency in long passes, shooting, peak speeds, and accelerations/decelerations(7).

This phase targets any "outlier” injury-specific deficits not addressed by power or reactive strength measures. Deficits from earlier phases increase the risk of re-injury and performance decline.

9. Grass phase four – Return to training

The athlete undergoes a graded, gradual return to team training, with expectations aligned among all role players. Initially exempt from contact, the athlete progresses to partial and full contact, the duration of which depends on their injury.

Early in this phase, cognitive overload may be high due to the athlete’s drive, peers, and coaching input, increasing injury risk if not managed carefully. More severe injuries, like an ACL, require longer progression than minor soft tissue injuries, which may allow a return within a day(5).

The goal is to restore normal team training loads while monitoring injury criteria. Coaches, the performance team, and the athlete assess readiness to progress. Exiting early can increase injury risk by 50% for the first match back(8).

“The objective, data-driven, step-by-step approach should improve athlete engagement…”

10. Grass phase five – Returning to play

Coaches or trainers should monitor a gradual increase in match minutes (<30, <60, then 90), starting with lower-level games to ease the athlete back in at a slightly reduced intensity. They increase the regular training time and closely monitor the athlete’s response. This is especially important during the first two months of match play(8–10).

11. Grass phase six – Return to performance

The athlete returns to match play with no limitations or concerns from a physical or psychological perspective and is available for unrestricted selection. Ideally, they should be achieving pre-injury-level performance criteria (or better). The MDT should continue to monitor the athlete from a distance and gradually step away as they successfully integrate into the group or their pre-injury performance level.

This new pathway, rooted in evidence-based criteria, adapts to various injuries across different sports and levels. Clinicians must use precise terminology and effectively communicate the criteria and progressions to all role players, particularly athletes, throughout rehabilitation. As the athlete transitions through each phase, from initial recovery to return to play, consistent monitoring of performance metrics and injury history remains essential to ensure a safe and successful reintegration into the team.

References

1. J. Orthop. Sport. Physiother. 2024 2, 1–23.

2. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018 0, 1–2.

3. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018 00, 1–7.

4. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020 15, 611–623.

5. Sports Medicine 2022 52.

6. Speci. J. Orthop. Sport. Phys. Ther. 2019 49, 570–575.

7. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2020 0.

8. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019 0, 1–6.

9. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016 50, 751–758.

10. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011 45, 553–559.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.