You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Posterior heel pain: the Physiotherapist's Achilles' heel?

Posterior heel pain is a common complaint seen in outpatient clinics. Just as all elbow pain is not tennis elbow, all posterior heel pain is not Achilles tendinopathy. Samantha Nupen explores the many structures that could cause posterior heel pain and the aggravating factors.

Christina Carreira and Anthony Ponomarenko of the United States skate in the Ice Free Dance program during the ISU Four Continents Figure Skating Championships at Broadmoor World Arena. Mandatory Credit: Michael Ciaglo-USA TODAY Sports

In Greek mythology, Achilles was a hero with one weakness – his heel. According to legend, his mother, Thetis, held him by one heel when she dipped him in the river Styx as an infant. This created a weak spot. Alluding to this legend, the term "Achilles’ heel" has come to mean a point of weakness, especially in someone or something with an otherwise strong constitution(1). The Achilles tendon is named as such because it is where Thetis held Achilles.

Things to assess with posterior heel pain

o Gait

o Balance/proprioception

o Big toe extension

o Medial arch strength

o Calf muscle endurance

o Equipment

o Training

o Overloading or overuse

o Structures

The Achilles tendon

Achilles tendon rupture (ATR)

The most devastating and probably easiest to diagnose, an ATR injury, is a complete rupture. Common in lunging sports like tennis, squash, and more recently, padel. Athletes report an acute injury, characterized by a loud popping sound (often as loud as a gunshot) or the feeling that an opponent has hit the athlete with a racquet on the back of the heel and then difficulty walking.

Clinically, the Thompson (Squeeze) test is positive, and management may be conservative immobilization or surgical intervention followed by a prolonged rehabilitation period. There is often a family history of a complete rupture, and the estimated heritability of the liability to ATR is as high as 50%. This generates the hypothesis that genetics play a role in the pathological changes in the tendon prior to rupture(2). It is also common to rupture one Achilles tendon and then, years later, rupture the other one.

Achilles tendinopathy

Achilles tendinopathy is common, and a lot has been written about it. As with all tendons, it takes time to improve. This is frustrating for both the athlete and the Physiotherapist. It is an overuse injury directly related to loading and repetitive strain that is very common in endurance sports. It can be emotionally devastating when practitioners tell these athletes to rest.

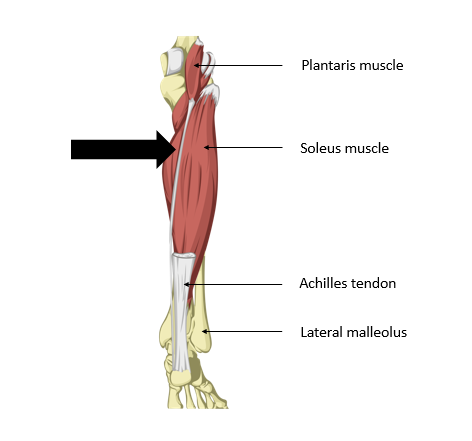

The key to successful treatment is an accurate diagnosis. Mid-substance tendinopathies tend to respond to treatment more quickly. Insertional tendinopathies can be more stubborn, so accurately assessing the area affected is important. More proximal medial pain could be caused by the plantaris tendon crossing over the Achilles tendon (see figure 1). The area of pain will impact treatment and management choices.

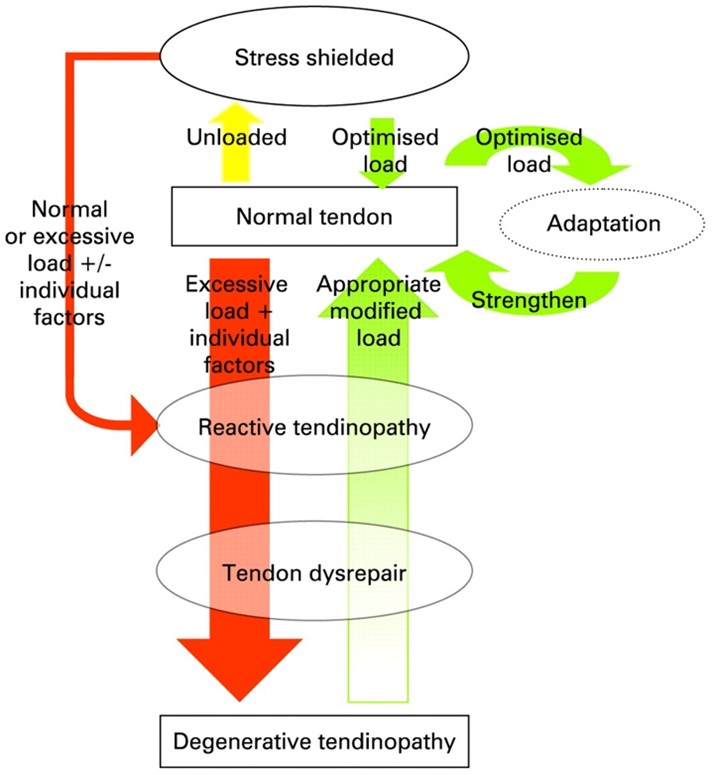

The state of the tendon also has an impact on management. Cook and Purdam’s model of the tendinopathy continuum is useful in determining the state of the tendon and predicting the recovery potential (see figure 2)(3). Reactive tendinopathy responds well to managing load and minimizing compression forces and is completely reversible. Tendon dysrepair implies an element of change to the structure of the tendon. Although these changes may not be reversible, it is possible to rehabilitate a fully functional, strong tendon with some structural disruption in the remaining tendon. Degenerative tendinopathy is seldom reversible. Assessing where the patient is on this continuum guides the management plan.

Basic principles of Achilles tendon management

o Unload

o Manual therapy to release the calf

o Joint mobilization of the foot and ankle

o No stretching or compression

o Isometrics

o Gradual loading

o Correction of biomechanics or contributing factors

o Return to sports

Plantaris

Plantaris weakly plantarflexes the ankle joint and flexes the knee joint in conjunction with the calf muscles. It is a weak antagonist to the tibialis anterior. Evolutional studies suggest that it is a rudimentary muscle that plays a minor role in gait. It is suggested that it is superfluous, but it has a high proportion of muscle spindles, indicating its importance in providing proprioceptive feedback regarding the foot’s position(4).

The plantaris tendon crosses the Achilles tendon medially and is often the cause of friction as it tightens and rubs against the Achilles tendon when it contracts. Clinically pain at the point where plantaris crosses the tendon is definitive. It is helpful to use soft tissue techniques from the medial Achilles proximally all the way to the plantaris muscle to release any possible tightness. Sometimes this super thin tendon ruptures spontaneously, releasing the friction, and the frictional tendinopathy recovers quickly. In other instances, a surgical release may be necessary and sacrifices the proprioceptive benefit of plantaris (see figure 3).

Sever’s disease

Sever’s disease is easily diagnosed clinically and presents with a typical history. Also known as calcaneal apophysitis, patients are between eight and twelve years old, generally very active, and play high-impact sports on hard surfaces, especially barefoot. Often these children "do it all" and love being on the sports field, making it difficult to slow them down. However, Sever’s does slow them down because the pain significantly affects their performance. The pain gradually increases and is often most severe during a growth spurt. There is not typically a traumatic event.

Along with the typical history, compression of the calcaneus, where the calcaneal apophysis attaches to the main body, will reproduce the patient’s pain. X-rays are not required except to exclude any more sinister finding or if there happens to be suspicion of a traumatic event. In severe cases, there is sometimes increased sclerotic density of the calcaneal apophysis on X-ray. The calcaneal apophysis is typically fragmented, and this radiological finding should not cause alarm(6).

Sever’s is a self-limiting condition, and symptoms ease as the growth plates begin to close. Before then, modified activity to unload the area, rest, stretching, heel raises, and better footwear all help.

Posterior ankle impingement syndrome

Posterior ankle impingement syndrome (PAIS) is characterized by posterior heel pain with repeated plantarflexion. Bony anatomical causes include the presence of an os trigonum or Stieda’s process, a bony extension of the posterior talus(7,8,9).

Os trigonum syndrome

An os trigonum is an unfused accessory bone posterior to the talus. It is generally an asymptomatic coincidental radiological finding and is present in up to 49% of the general population. It has been argued that dancers and sports which plantarflex repeatedly have a higher incidence of os trigonum. However, there is no evidence for this. There is also no evidence that these kinds of activities as a young child result in the non-fusion of the os trigonum.

It is a common radiological finding in ballet dancers, fast bowlers, and soccer players who hyper-plantarflex their ankles. Still, it does not always cause their posterior heel pain(10). Often surgical intervention is recommended when X-rays show an os trigonum present in these young athletes, but the clinical picture may not fit with os trigonum syndrome. This unnecessary surgery could be devastating for future dancing or sports participation.

Ballet dancers repeatedly complete forced plantarflexion when en pointe. There is no doubt that this repeated plantarflexion will compress the os trigonum(11). Furthermore, they tightly tie the ribbons and cross the Achilles tendon, causing a possible frictional tendinopathy (see figure 5). Accurate diagnosis is key to good management of these athletes.

Os trigonum syndrome is when the soft tissue structures around the accessory bone become symptomatic(12). This could be after an acute, severe ankle sprain or due to overuse with repetitive plantarflexion, which compresses the os trigonum and deep posterior structures and causes irritation of the flexor hallucis longus tendon. If the tendon is involved, there will be pain with a combined plantarflexion and big toe extension, as is common in the demi pointe position in ballet.

Conservative treatment (such as rest, immobilization that limits plantarflexion activities, stretching, and manual therapy) is highly effective. Surgical intervention should only be considered as the very last resort.

Conclusion

The human foot is an intricately incredible design. This article only touches on the posterior heel. There are so many nuts and bolts and moving parts that miraculously, usually, all work. Athletes rely on healthy, strong feet to be effectively mobile and to perform well. A thorough understanding of anatomy, biomechanics, and clinical presentations is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management of posterior heel pain. There is no need for the posterior heel pain to be the Physiotherapist’s weakness. Practitioners have the knowledge to make an enormous difference in these athletes’ lives.

References

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achilles

- Foot and Ankle Surgery 28 (2022) 1050–1054

- Br J Sports Med 2009;43:409–416

- sportdoctorlondon.com/plantaris-tendon/

- Am Fam Physician. 2018 Jan 15;97(2):86-93

- J Orthop Surg Res. 2022 Feb 9;17(1):83

- Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2008 Jun;12(2):154-69

- J Orthop Surg Res. 2016; 11(1): 97

- North Clin Istanb. 2022; 9(1): 23–29

- J Osteopath Med 2022; 122(5): 271–272

- Clin. Anat. 23:613–621, 2010

- J Orthop Surg Res. 2016 Sep 9;11(1):97

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.