Neck Injury in Sport: Management and Rehab

In her previous article, Kay Robinson looked at neck injury assessment. In this article she focuses on injury management and rehabilitation, with the goal of a return to full performance

Having read part one in this series, clinicians can hopefully see the merit in assessing the cervical spine’s competency when screening and monitoring – particularly in sports where athletes are at risk of neck injuries due to axial loading, prolonged position exposure, whiplash and external forces such as vibrations and G force.

This article looks at treatment strategies for all neck dysfunctions, from acute injuries to returning athletes to their performance environment in peak conditions. As with all injury management processes, there needs to be a clear understanding of the injury and planned rehabilitation by the athlete and high-performance team/coaches. For the sake of simplicity, we will break down this rehabilitation into four stages:

- Early management

- Initial rehabilitation

- Rehabilitation progression

- Return to performance.

Early Management

This stage of rehabilitation should begin as soon as any serious cervical or head injury has been excluded following thorough medical assessment and further investigation if appropriate. The key goals in early management following neck injury are reducing pain and muscle spasms and restoring normal range of motion.

High-quality evidence on the management of acute cervical pain is lacking. However, empirical evidence supports a combination of therapeutic modalities, including massage, electrical stimulation, heat, analgesics, and range of motion exercises(1). This should be combined with postural education and ensuring there aren’t compensatory dysfunctions throughout the rest of the kinetic chain, especially the shoulder girdle, thoracic, and lumbar spine.

Initial treatment should be carried out with the neck in neutral alignment and a ‘gravity-eliminated’ position to reduce any nerve root, disc, or facet joint irritation and limit the involvement of overactive superficial muscles.

Gentle range of movement has good analgesic qualities. It should begin as soon as possible, taking care not to commence aggressive stretching of the muscles in spasms, which may reduce the stability of the neck(2). Research shows that in patients with neck pain, the key stabilizers (deep neck flexors) become inhibited; therefore, they must be retrained before further rehabilitation or loading(3).

Deep neck flexor training can begin immediately and is carried out using the stages as described by Jull et al. (2008) in the Cranio-Cervical Flexion Test (see article part I) using a pressure cuff for feedback and working through progressive pressure increases and holds(4). Once the athlete can achieve this, avoiding compensation strategies, the routine should be done independently and regularly throughout the day. It can be progressed to more gravity-challenging and sport-specific positions.

Following the reduction of acute symptoms, the restoration of cervical motion in all planes required for the athlete’s sport, and the ability to activate and maintain deep neck flexors, the athlete can progress to initial rehabilitation.

Examples of strengthening exercises (following sessions to familiarize athletes with technique)

| Movement | Reps | Rest (min) | Sets | Rest (mins) | Intensity (% of one rep max) |

| Cervical flexion | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 60-70% |

| Cervical extension | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 60-70% |

| Cervical side flexion | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 60-70% |

| Cervical rotation | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 60-70% |

Initial Rehabilitation

This rehabilitation stage is paramount in building neck mobilizer strength without exposing the musculature to excessive forces. Monitoring and screening data should be used where available to aid programming. Full range of motion and DNF strengthening should continue throughout this stage.

Commonly, when managing peripheral joint injuries, isometric strengthening is prescribed, and yet it is often overlooked following cervical injury. Again, this begins in a neutral, gravity-eliminated position and progresses to standing, followed by sport-specific positions.

For example, in the sport of Skeleton, the athlete needs to maintain a neck position prone on the sled. Motorcyclists must maintain neck position while on a bike and, therefore, must have their balance challenged alongside strengthening. It is also essential to consider any worn helmets or headgear, as this can be introduced at this stage.

Initial strength training should begin at a medium volume and low intensity and be gradually increased in terms of repetition, length of contraction, and sets. Throughout this stage, athletes should be monitored for any reproduction of symptoms, loss of range, and any change in shoulder kinematics. During assessment, considerations should be made to stabilize the torso and minimize lower limb involvement to ensure proper neck strengthening.

Rehabilitation Progression

Once asymptomatic, and when isometric contraction of 100% MVC and a full range of motion have been achieved, the focus should progress to eccentric and concentric neck strengthening through the range. This is commonly identified as a weakness through screening and, therefore, can be used in athlete development and return from injury.

The athlete’s background should be considered carefully when programming. For instance, rugby players will likely have considerably more exposure to neck strength training previously than a young gymnast returning from injury.

Through-range strengthening should be higher volume and medium intensity and carried out using manual or dynamometry resistance. Initially, cable machines may lead to overload, but they can be used as a progression. Movements should begin in the sagittal plane and incorporate coronal and transverse plane strength.

Principles of overload should be maintained with neck strengthening; small gains should be expected to occur gradually rather than seeing sudden spikes in training. This is particularly important when understanding the anatomy and the need for stability across many small joints.

Once baseline strength has been regained, sport-specific neck training can begin. In contact sports, tackle bags can be used to replicate controlled contact. Divers may return to low board dives, and drivers to simulation work.

If athletes are exposed to external forces such as G force and vibration, this should be replicated as rehabilitation and injury prevention. If the athlete remains pain-free, has strength comparable to baseline measures, has no change in shoulder or trunk kinematics, and has participated in controlled normal training situations (including additional external forces). The athlete can progress to return to performance.

Methods of Isometric Neck Strengthening

- Handheld dynamometer: Athletes should begin carrying out 30% of their maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) to learn the technique. Over sessions, they should incrementally increase to performing 100% MVC.

- Cable/pulley system: Using a head harness, the mass on the pulley system should be set to avoid any overload.

- Manual isometric strengthening: Manual contraction is performed against a static surface or body part. It can be easily done in all environments but cannot measure/limit loads.

Return to Performance

The final phase of rehabilitation from neck injury combines the strength training that the athlete has honed, emphasizing the restoration of specific skills required to return to their particular sport and regaining confidence in being exposed to forces on the cervical spine.

Incorporating the aspect of unanticipated load is crucial at this stage. Training pre-activation of cervical muscles to brace against impacts could decrease neck and head injuries in sports(5). This training mode should be practiced in rugby before going into a contested scrum situation, before heading a football, and when tumbling in gymnastics. Combining training approaches such as isometric, isokinetic strengthening, exposure to vibration, and impacts in and out of the sport-specific setting increases the chance of adapting neural elements, resulting in optimal motor skill, muscular control, and coordination.

As with any injury, return to performance programming is injury and athlete-specific. As such, the decisions leading to return to play should be centered on the individual athlete but involve the entire interdisciplinary team. The athlete should be physically and psychologically ready to return with all strength, skill, and confidence deficits addressed to reduce the risk of further injury and maximize the individual’s performance on return.

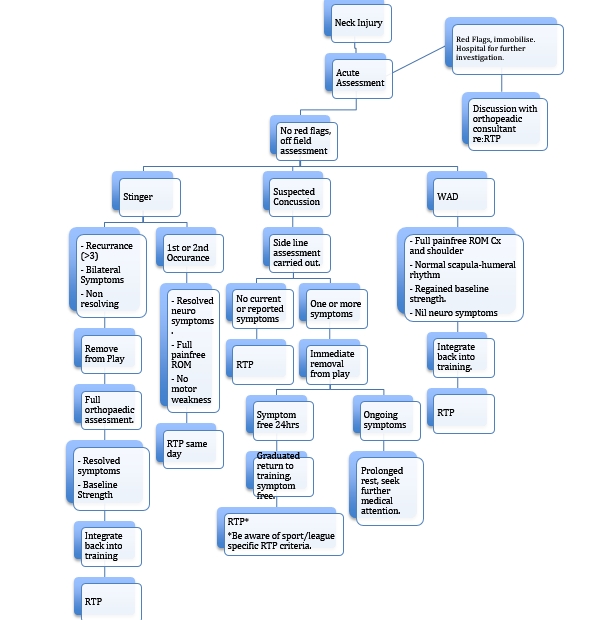

Return to performance (RTP) protocols will vary depending on the injury, sport, and position the athlete is returning to. Clinicians must know the evidence to guide critical contraindications when returning to play following common neck injuries (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Return to play guidelines and contraindications

The timing of post-injury neck training should be carefully considered when programming as part of a strengthening regime; neck strengthening is known to be fatiguing, and strength is initially reduced for up to a day post-loading (likely longer in females)(6). Therefore, heavy neck-strength training followed by a return to performance in quick succession should be avoided to minimize the risk of further injury.

Sports with heavier schedules and fewer recovery days should focus on heavier neck strengthening in pre, or mid-season breaks for optimal gains. This should also be an essential reason to test the athlete’s performance under varying levels of tiredness and ensure they are robust enough to withstand the forces they are exposed to while competing.

Summary

All neck weakness and movement dysfunctions found through assessment and screening should be addressed immediately to prevent further injury. Rehabilitation should progress from regaining range of motion and strengthening the neck and surrounding structures to sport-specific training. A deep understanding of sport-specific demands and loads the neck is subjected to is crucial for practitioners to deliver optimal rehabilitation. This can be aided by using baseline data and ongoing research into the area. By following a clear assessment and rehabilitation protocol specific to individuals, we can minimize further injury and ensure that athletes return to optimal performance with the required strength and movement attributes.

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Injury Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.