You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Morton’s neuroma: clinical assessment and management

A Morton’s neuroma is an enlargement of the nerve branches of the intermetatarsal spaces of the forefoot. The nerve between the third and fourth metatarsal bones (80-85%) are most often affected and less common is the nerve between the second and third metatarsal bones (10-15%) (see figure 1)(1).

Importantly, however, since no nerve damage has been sustained, Morton’s neuroma doesn’t present as a typical neuroma. Therefore, more appropriate terms such as ‘intermetatarsal nerve entrapment’ or ‘Morton’s entrapment’ may be more suitable as the nerve becomes compressed between the metatarsal heads of the forefoot(2). However, while the term ‘entrapment’ should be acknowledged, Morton’s neuroma will be the term used here as this is the term used in the literature.

Figure 1: Frequently diagnosed location of a neuroma

Morton’s Neuroma is diagnosed more frequently in females, and although the incidence rate is higher in the 40-50-year-old age group, those in their teens and twenties can also be affected(3). A Morton’s neuroma is often diagnosed in athletes that wear tight fitting footwear or in those who place high loads on the feet such as in ballet dancers or runners(4). In particular, runners who have increased extension of the third metatarsophalangeal joint relative to the fourth metatarsophalangeal joint have an increased incidence of Morton’s Neuroma(4).

Although the precise causes of Morton’s neuroma are unclear, most expert authorities agree that repetitive trauma to the plantar digital nerve (positioned between the transverse intermetatarsal ligament and the surrounding fascia) during physical load is likely to be a key factor.

Signs and symptoms

It is essential to be aware of the clinical signs and symptoms that patients may describe during a subjective examination. These may include a dull or sharp pain, numbness or tingling, burning sensation, cramping, or walking with the feeling of ‘a stone in the shoe’(1). Walking and wearing tight-fitting shoes may exacerbate the symptoms, whereas the removal of footwear together with rest and massage is likely to alleviate the symptoms(4). It is important to recognize that a patient may describe different pain presentations throughout the day. Following compression (perhaps from tight-fitting footwear or following heavy loading) pain may be intense for five to ten minutes, followed by a dull ache for two to three hours(5).Assessment and diagnosis

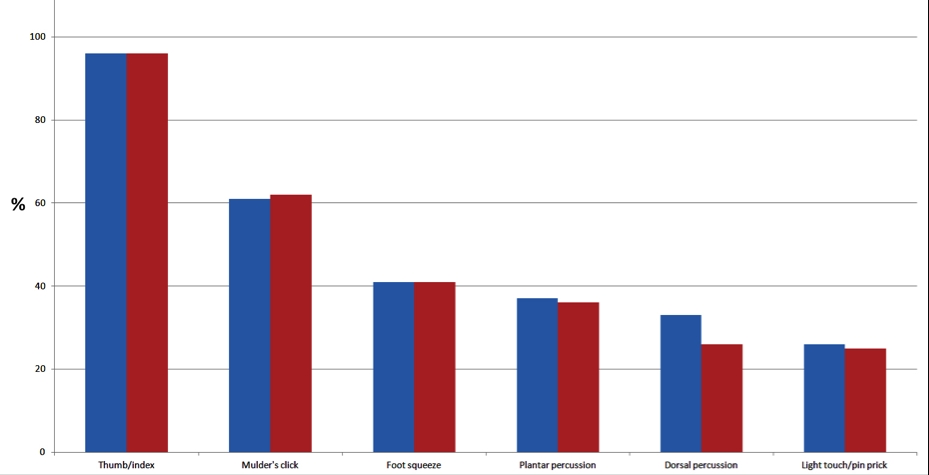

A Morton’s neuroma can be clinically assessed through a variety of tests. Researchers from the University Hospital of Leicester have studied the sensitivity and accuracy of different clinical tests used for diagnosing Morton’s neuroma(6). (The ‘sensitivity’ of a test can be explained as the proportion of people who test positive for a condition among those who actually have the condition.)The tests (see figure 2 and table 1) included:

- The thumb/index finger squeeze (96% sensitivity, 96% accuracy)

- Mulder's click (61% sensitivity, 62% accuracy)

- Foot squeeze (41% sensitivity, 41% accuracy)

- Plantar percussion (37% sensitivity, 36% accuracy)

- Dorsal percussion (33% sensitivity, 26% accuracy)

- Light touch and pinprick (26% sensitivity, 25% accuracy)

Of note, however, is that while the thumb index finger squeeze test was more sensitive in diagnosing a typical Morton’s Neuroma, the Mulders click test was a significantly more effective test in diagnosing the larger neuromas.

Figure 2: Summary of test sensitivity (blue) and accuracy (red)

| Name of test | Description | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Thumb index finger squeeze test | This test is done by holding the forefoot with one hand (by clasping all five metatarsal heads with one hand) and then applying pressure to the top and bottom of the intermetatarsal space with the thumb and index finger of the other hand. Pain is indicative of Morton’s neuroma. |  |

| Mulders click test | Apply compression to the forefoot by clasping the five metatarsal heads with one hand, and then applying pressure to the intermetatarsal space by using the soft end of a tendon hammer or a pen on the sole of the foot. An audible click coinciding with pain is indicative of Morton’s neuroma. |  |

| Foot squeeze test | Clasping the forefoot with both the left and right hands and squeezing the metatarsal bones together with either hand and compressing the intermetatarsal nerve. Pain is indicative of Morton’s neuroma. |  |

Morton’s neuroma can be diagnosed using either an ultrasound or an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan. A systematic review and meta-analysis carried out by two researchers from the University of Genoa selected 14 studies (from 277 identified articles) that measured the diagnostic accuracy of Morton’s neuroma(7). No significant difference between diagnostic ultrasound and MRI was found to exist in the accuracy of diagnosing such a lesion. It could be argued however that an MRI is more sensitive at identifying other disorders that ultrasound is unable to identify (such as those outlined in box 1). Merve et al did, however, establish that the specificity for MRI was lower for Morton’s neuroma (68%) compared to ultrasound (88%)(1). Specificity can be defined as the amount to which a diagnostic test is specific to a particular condition.

Box 1: Conditions of the foot to be used as a differential diagnosis for forefoot pain(5)

- Intermetarsal bursitis

- Plantar plate rupture

- Metatarsophalangeal joint capsulitis

- Metatarsal stress fractures

- Metatarsalgia

- Lumbar radiculopathy

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome

- Frieberg's infraction

- Infection

- Tumors (such as synovial sarcoma)

- Painful callosities

- Rheumatoid nodule

- Peripheral neuropathy

Non-surgical management

All non-surgical means should be explored before more invasive techniques are used to manage this condition. It is well known that a metatarsal pad can be used to offload the intermetatarsal space during loading(8). In addition, high-heeled shoes should be avoided as well shoes with a thin sole also as they may increase compression forces in the region of the bottom of the foot. If a foot pad is not effective after three months of use the current NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence) guidelines recommend referral to an orthotist to prescribe custom-made orthotics(8). If footwear modification and orthotics are ineffective then referral to a consultant with a special interest in the foot is justified.Case study

A case report detailed the treatment of a 35-year-old female runner who presented with pain between the third and fourth metatarsal space on walking, running and whilst wearing heels(9). She was diagnosed with Morton’s neuroma and had received a steroid injection two months previously with no effect. Prior to undergoing surgery, the patient was referred to a physiotherapist for an assessment. The pain increased to 6/10 (VAS scale of 0-10) during loading and settled quickly whilst resting. Shoe modification and orthotics were applied and had helped, but weren’t effective over the long term. The patient stopped running and wearing heels completely, and avoided stairs due to the pain. She was keen to return to running.Examination indicated a positive thumb/index finger squeeze test. The patient’s pain was reproduced when applying pressure of the fourth metatarsal bone, from the top of the foot, on the cuboid bone. The physiotherapist identified mid foot hypomobility, which was contributing to pressure on the lateral forefoot, and applying pressure to the third plantar digital nerve during stance and toe push off.

Initial treatment included a grade four plantar mobilization glide of the talonavicular joint for four minutes. Following this, the patient reported reduced pain in the space between the third and fourth metatarsals on palpation. The patient was instructed on self-mobilization techniques to do at home. After six treatments focusing on mobilizations of the midfoot to restore normal foot biomechanics, the pain had eased and by session 12 (three months after the initial presentation) the patient had completed a two-mile run and wore heels pain free.

Surgical management

It is commonly aired view within the scientific literature that conservative means for treatment of Morton’s neuroma are ineffective, and that steroid injection or surgical excision is more effective – or indeed, the only solution. To test this, researchers randomly assigned eighty-two patients who had been diagnosed with Morton’s neuroma to either a footwear modification (with orthotics) only group or footwear modification with a steroid injection at the initial assessment(10).Overall, there was a significant difference between the two groups at three, six and twelve months follow up, with the patients receiving footwear modification plus steroid injection being more satisfied. At the 12-month review, 83% of patients who received a steroid injection were either pain-free or had had relief of pain. This is in contrast to 63% of patients who had orthotics with footwear modification. However, when the results obtained for twelve months were analyzed in depth, they weren’t statistically significant to those obtained in the footwear modification only group.

Barratt and colleagues have suggested that although steroid injections may provide temporary relief, their long-term effectiveness is questionable(2). The damage to the surrounding fatty tissue and the plantar plate (a thickened ligament that functions to prevent the toes from hyper-extending) is possible over the long term. In addition, alcohol injection techniques should be avoided to prevent damage to neural and surrounding tissues, and have been shown to have poor long-term results.

A variety of surgical techniques have been described for treating this condition such as excision of the neuroma or intermetatarsal ligament release(5). To excise the lesion, an incision can be made either on the top or the sole of the foot, each presenting with varying complications(5). One complication with an approach from the bottom of the foot is the formation of scar tissue, which may be painful when subjected to pressure. A further restriction is that weight bearing is limited for two weeks, whereas an incision from the top of the foot allows for early weight bearing(3).

A normal recovery protocol following surgery on the top of the foot, is two weeks in a post-operative shoe, with the removal of stitches after two weeks. After three to four weeks a patient can transfer into a normal shoe and then resume sport within four to six weeks(5). An incision from the bottom of the foot, however, requires the stitches to remain in for an extra two weeks and therefore extends the recovery protocol.

Despite the potential for a number of complications following surgery for excision of a Morton’s Neuroma, studies suggest that 80-96% of patients report they are satisfied with the overall outcome(5). Some of the complications that did occur arose from the formation of keloid scarring (2.2%), which presents as hard or rubbery areas raised above the level of the skin surface, which may be shiny and hairless. A keloid scar can be painful or itchy and sometimes doesn’t present until months after surgery. Furthermore, it may restrict movement at a joint. It is also reported that more than 30% of cases reported numbness in the relevant toes and present with a positive Tinels sign(11). In addition, there is a risk of wound infection as reported by 1.1% of cases(5). Moreover, there is a risk of recurring formation of the neuroma, and patients should be informed of this.

Summary

In summary, while the results for Morton’s neuroma are promising following surgery, in the opinion of this author, it is the role of the physiotherapist or sports therapist to effectively treat by exploring all conservative options before referring for surgery. If surgery is indicated, it is recommended to maintain overall body conditioning through non-load bearing exercises during the rehabilitation period.References

- Pain Phys, 2016, Feb, 19: E355-E357.

- www.aens.us/images/aens/AENSGuidelinesFinal-12082014.pdf

- Ochsner Journal, 2016, 16, 471–474.

- Int J of Clini Med, 2013, 4, 19-24.

- www.aofas.org/PRC/conditions/Pages/Conditions/Mortons-Neuroma.aspx

- The J of Foot and Ankle Surg, Aug, 2015, 54, 4, 549–553.

- Euro Radi, August, 2015, 25, 8,2254–2262.

- cks.nice.org.uk/mortons-neuroma#!scenariorecommendation

- Man Thera, 2016, 21, 307 – 310.

- Am Ortho Foot and Ankle Soc, July, 2005, 26, 7, 556-559.

- ACO, July, 2002, 10, 1, 45-50.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.