You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Lumbar Disc Herniation - Part I: Signs, Symptoms, Selection

In the first of a two-part article, Chris Mallac looks at the lumbar spine disc herniation. What are the likely signs and symptoms associated with disc herniation, and what are the selection criteria for micro-discectomy surgery in athletes?

Great Britain’s Andy Murray holds his back in pain during French Open, 2009. Credit: Action Images / Scott Heavey Livepic

Low back pain is a reasonably common complaint in both the young college age athlete and professional athlete, and it has been estimated that more than 30% of athletes complain of back pain at least once in the career(1). The cohort of back injuries that can affect the athlete include disc degeneration, disc bulge/herniation, facet joint arthropathy, spondylosis , spondylolisthesis, muscle spasm and stress fractures.

Lumbar spine disc herniation is one type of lumbar injury that can not only cause debilitating low back pain, but can also compress nerve roots and create radicular referral of pain into the lower leg with associated sensation changes and muscle weakness. This injury will not only affect the short-term competition ability of the athlete, but may also reoccur and become chronic possibly resulting in a career ending injury. Managing disc herniation in the athlete usually begins with conservative treatment and if this fails, surgical options are considered. However, often elite athletes will request a faster resolution to their symptoms to minimise time away from competition. Therefore, providing the criteria for lumbar spine surgery are indicated, the conservative period will often be compressed, and surgery will be sought earlier. The favoured surgical procedure for the athlete with a disc herniation is the lumbar disc micro-discectomy.

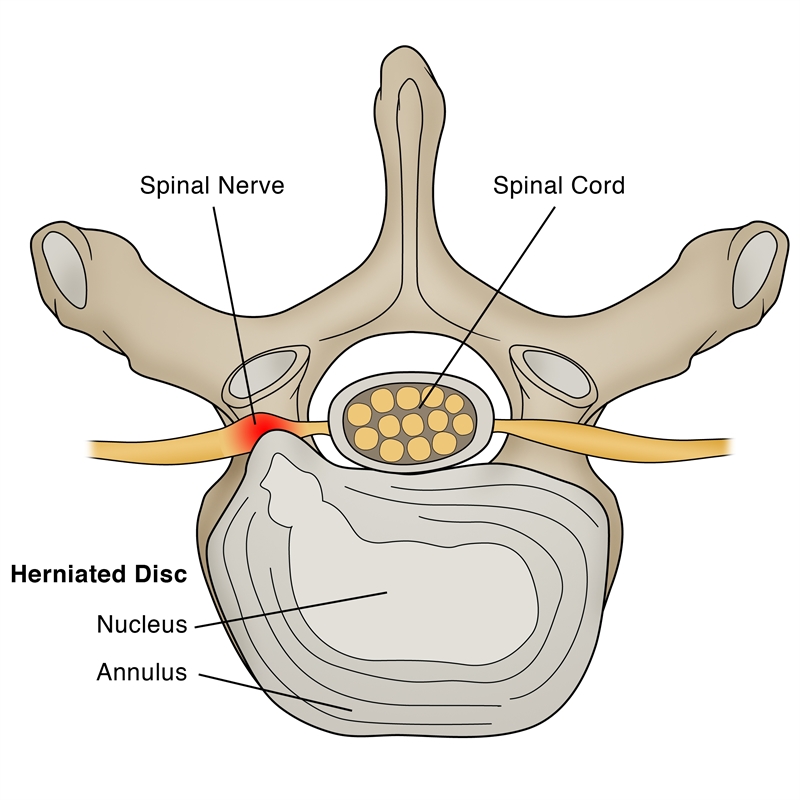

Figure 1: Schematic representation of herniated lumbar disc

Anatomy and biomechanics

The lumbar spine intervertebral discs play a crucial biomechanical role within the spine, allowing for motion between the spinal segments while dispersing compressive, shear, and torsional forces(2). These discs consist of a thick outer ring of fibrous cartilage termed the annulus fibrosis (akin to the onion rings surrounding the core of an onion), which surrounds a more gelatinous core known as the nucleus pulposus, which is contained within the cartilage end plates inferiorly and superiorly.

The intervertebral disc comprises cells and substances such as collagen, proteoglycans, and sparse fibrochondrocytic cells, which allow the transmission and absorption of forces arising from body weight and muscle activity. To do this, the disc relies mainly on the structural condition of the nucleus pulposus, annulus fibrosis, and the vertebral endplate. If the disc is structurally normal and functions optimally, forces are spread across the disc evenly(3).

However, disc degeneration (cell degradation, loss of hydration, disc collapse) can decrease the ability of the disc to withstand extrinsic forces, as forces are no longer transmitted and distributed evenly. Tears and fissures in the annulus can result, and the disc material may herniate with sufficient external forces. Alternatively, a sizeable biomechanical force placed on a healthy, normal disc may lead to extrusion of disc material as a result of catastrophic failure of the annular fibers – examples include a heavy compression type mechanism due to a fall on the tailbone or strong muscle contraction such as very heavy weight lifting(4).

Herniations represent protrusions of disc material beyond the confines of the annular lining and into the spinal canal (see figure 1)(5). If the protrusion does not invade the canal or compromise nerve roots, back pain may be the only symptom. However, if the extruded disc material contacts or exerts pressure on the thecal sac or lumbar nerve roots, radicular pain may be generated along with neurological symptoms such as numbness and paraesthesia.

The pain associated with lumbar radiculopathy occurs due to a combination of nerve root ischemia (due to compression) and inflammation (due to neurochemical inflammatory mediators released from the disc). During a herniation, the nucleus pulposus places pressure on weakened areas of the annulus and proceeds through the weakened sites, ultimately forming a herniation(6). It follows that some form of disc degeneration may exist before the disc can be herniated(7).

Compared to other musculoskeletal t issues, discs tend to degenerate earlier in life, with some studies showing adolescents presenting signs of degeneration between the ages of 11 and 16(8). With increasing age, there is further degeneration of the intervertebral discs. Powell et al. (1986) observed that more than one-third of healthy subjects aged 21-30 had degenerated discs(9).

While the disc may be at risk of injury in all fundamental planes of motion, it is particularly susceptible during repetitive flexion, or hyperflexion, combined with lateral bending or rotation(10). Traumatic events such as excessive axial compression can also damage the internal structure of the disc. This can occur due to a fall or strong muscular forces developed during tasks such as heavy lifting.

Athletes are commonly exposed to high-loading conditions. Examples of this include:

- World-class powerlifters, where the calculated compressive loads on the spine are between 18800 Newtons (N) and 36400N acting at the L3-4 motion segment(11).

- Elite-level football linesmen who have been shown to present time-related hypertrophy of the disc and changes in vertebrae endplate in response to the repetitive high loading and axial stress(12).

- Long-distance runners have been shown to undergo significant strain on the intervertebral disc, indicated by a reduction in disc height(13).

Herniations can be classified based on location, such as central, posterolateral, foraminal, or far lateral(14). The herniation morphology can also be classified as protrusion, extrusion, or sequestered fragment. Finally, herniations are also identified based on level, with most herniations occurring at the L4/5 and L5/S1 intervertebral disc levels; these can then affect the L5 and S1 nerve roots, leading to clinical sciatica(15). Upper-level herniations are less common, and when they do occur with radiculopathy, they will affect the femoral nerve. Finally, the prevalence of disc injury increases progressively caudally, with the most significant numbers at the L5/S1 levels(16).

Herniation in athletes

The offending movements implicated in creating disc herniation and the sports involved are usually sports with combined trunk flexion and rotation(17). The 20-35 age group is the most common group to herniate a disc, most likely due to the fluid nature of the nucleus pulposis and due to behavior(18). This age group is likelier to be involved in sports requiring high loads of flexion and rotation and are reckless with their postures and positions during loading.

The sports most at risk of disc herniation are:

- Hockey

- Wrestling

- Football

- Swimming

- Basketball

- Golf

- Tennis

- Weightlifting

- Rowing

- Throwing events

These sports involve high loads or exposure to combined flexion and rotation mechanisms. Furthermore, those who participate in longer and more intense training regimes appear to be at higher risk of spinal pathologies, as do those involved in impact sports.

Athletes and Disc Degeneration

Various radiographic techniques reveal that athletes present with more cases of disc degeneration than the general population. For example, the evidence reveals that between male elite gymnasts and non-athletes, gymnasts are at a higher risk of disc degeneration than non-athletes. Herniation accounts for 43% of lumbar injuries in tennis players. Moreover, elite-level female gymnasts are at greater risk of experiencing disc degeneration. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed that 28 of 33 adolescent tennis players presented clinical symptoms, ranging from disc degeneration, disc herniation, pars lesions, and facet joint arthropathy. Interestingly, it has been found that female flamenco and ballet dancers had a lower prevalence of disc degeneration as measured by MRI when compared to age-matched non-athletic controls. This suggests that the type of physical activity influences the prevalence of disc degeneration in an athletic population. Load sports such as weightlifting were associated with a greater incidence of degenerative discs than runners.

Signs and Symptoms

The efficacy of management plans for lumbar spine disc herniation – regarding the decision to operate or treat conservatively – will be discussed in greater depth in part two of this series. However, the decision to operate an athlete is usually driven by the motivation and upcoming goals they set for themselves. They may prefer a relatively simple micro-discectomy rather than waiting for symptoms to abate through an extended rehabilitation period.

This conservative period of management may involve medication therapy, epidural injections, relative rest and trunk muscle rehabilitation, acupuncture, and osteo/chiropractic interventions. However, the typical presenting signs and symptoms that indicate a significant disc herniation that may require surgical intervention in the athlete include:

- Low back pain with pain radiating down one or both legs

- Positive straight leg raise test Radicular pain and neurological signs consistent with the nerve root level affected

- Mild weakness of distal muscles such as extensor hallucis longus, peroneal, tibialis anterior, and soleus. These would fit with the myotome relevant to the disc level

- MRI confirming a disc herniation

- Possible bladder and bowel symptoms

- Failed conservative rehabilitation

The elite athlete typically has a shorter period to allow conservative rehabilitation to be effective. In the general population, medical practitioners will most likely prescribe a minimum 6-week conservative treatment period with a six-week review on whether to extend the rehabilitation a further six weeks or seek a specialist opinion. The specialist may then attempt more medically orientated interventions such as epidural injections.

The athlete, however, will have these time frames compressed. They may be more willing to undergo an epidural very early in the conservative period to assess the effectiveness of this procedure. If no signs of improvement are evident in two weeks, they may opt to have an immediate lumbar spine microdiscectomy.

Imaging

MRI remains the preferred method of identifying lumbar spine disc herniation, as it is also very sensitive for detecting nerve root impingements(19). However, abnormal MRI scans can occur in otherwise asymptomatic patients(20); hence, clinical correlation is always essential before any surgical consideration. Furthermore, patients may present with clinical signs and symptoms that suggest the diagnosis of an acute herniated disc and yet lack evidence of sufficient pathology on MRI to warrant surgery.

Therefore, a volumetric analysis of a herniated disc on MRI may be potentially valuable in assessing the suitability for surgery. Several authors have cited the potential value of volumetric analysis of herniated discs on MRI as part of the selection criteria for lumbar surgery(21).

A study conducted at Michigan State University found that the size and location of the herniated disc determined the likelihood of surgery, with what researchers referred to as ‘types 2-B’ and ‘types 2-AB’ being the most likely candidates for surgery(22).

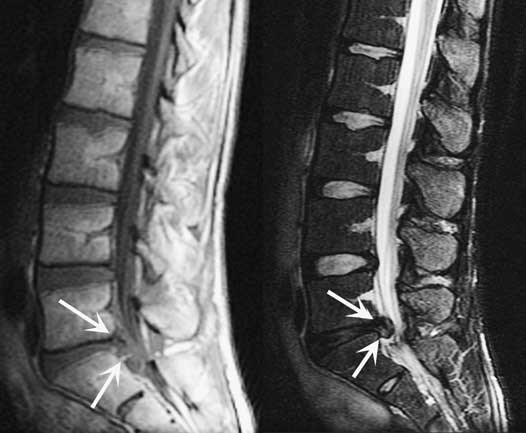

The MRI protocol for the lumbar spine consists of (see figure 2):

- Sagittal plane echo T1-weighted sequence

- Sagittal fast spin-echo proton density sequence

- Sagittal fast spin-echo inversion recovery sequence

- Axial spin-echo T1-weighted sequence

Figure 2: MRI lumbar spine disc herniation at L5/S1

The image on the left is a sagittal T1-weighted image; the image on the right is a sagittal-weighted T2 image.Summary

Disc herniations are not a common complaint in athletes, but they occur in sports involving high loads or repetitive flexion and rotation movements. Sufferers of a disc herniation will usually feel focused low-back pain, possibly with referral into the lower limb with associated neurological symptoms if the nerve root has been compressed. MRI remains the gold standard for identifying disc herniation and associated nerve root impingement.

Managing a disc herniation in an athlete is somewhat different to the general population as often the risk of a protracted failed rehabilitation period is bypassed for the more secure and low-risk micro-discectomy procedure. In the second installment in this series, we will discuss the exact surgical options involved and how to rehabilitate the elite athlete following a lumbar spine microdiscectomy.

References

- Sports Med. 1996;21(4):313–20

- Radiology. Oct 2007;245(1):62-77

- Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2003;5(3):120- 30

- The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American volume. Feb 2004;86-A(2):382 – 96

- Radiology. Oct 2007;245(1):43-61

- Spine. Sep 15 1996;21(18):2149-55

- Spine. May-Jun 1982;7(3):184-91

- Spine. Dec 1 2002;27(23):2631-44

- Lancet 1986;2:1366–7

- Disease-A-Month:DM. Dec 2004;50(12):636- 69

- Spine. Mar 1987;12(2):146-9

- The American Journal of Sports Medicine. Sep 2004;32(6):1434-9

- The Journal of International Medical Research. 2011;39(2):569-79

- Spine. 2001;26:E93-113

- Spine. 1990;15:679-82

- British Journal of Sports Medicine. Jun 2003;37(3):263-6

- Prim Care. 2005;32(1):201–29

- McGill, S.M. Low back disorders: Evidence based prevention and rehabilitation, Human Kinetics Publishers, Champaign, IL, U.S.A., 2002. Second Edition, 2007

- Spine. Mar 15 1995;20(6):699-709

- J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990 . 2:403–408

- J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2001. 9:1–7

- Eur Spine J (2010) 19:1087–1093

Further reading

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.