You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

It’s Never Just a Hamstring Strain

Samantha Nupen explores the intricacies of a “simple’ hamstring strain and what to assess and manage for an athlete to return to sport in the best possible shape.

Laura van den Heiden of the Netherlands shoots past Sweden’s Anna Lagerqvist and Isabella Gullden. TT News Agency/Thomas Johansson/via REUTERS

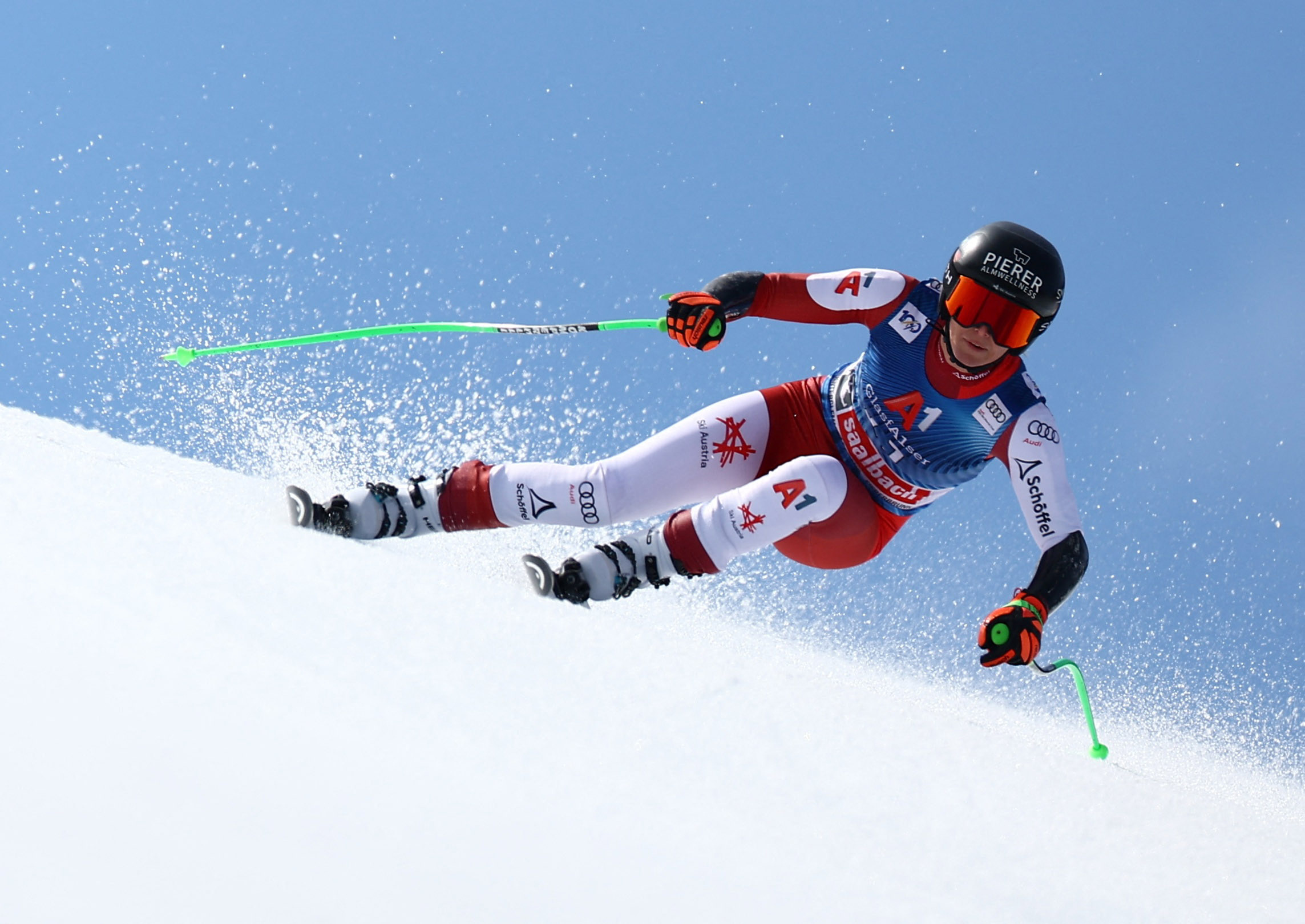

Hamstring injuries are prevalent in team sports that require high-speed sprinting and kicking, like rugby, football, and American football, where 12 -17% of all injuries are hamstring muscle strains(1). They are also common in non-contact sports like track and field, waterskiing, cross-country, downhill skiing, and running between the wickets or pace bowling in cricket.

Thirty-four percent of dance injuries are acute hamstring strains, and 17% are overuse(1). These overuse strains are more likely posterior thigh pain from another source(2). Clinicians classify soft tissue injury severity according to grades, and 97% of all hamstring strains are classified as grade I or II.

On average, grade I hamstring strains account for ±17 days of lost training or playing time, while grade II strains result in ±22 days away from sport(1,3).

In English professional soccer, there is an injury recurrence rate of 12 - 48%, and in Australian football, there is a 34% recurrence within one year of the original injury. The second hamstring injury is generally more severe and results in a significantly longer time away from sport.

Grade I and II hamstring strain symptoms are often negligible or absent at rest or in activities of daily living. This may tempt athletes to return to sport prematurely, resulting in re-injury and prolonged rehabilitation. Clinicians must clearly define an athlete’s return to sport timeline to prevent re-injury.

Mechanism of Injury

Most muscle strains occur during an eccentric contraction. The severity of the injury is dependent on the muscle strength and contraction velocity. A suddenly activated eccentric contraction is more likely to cause a severe muscle strain injury.

The biceps femoris and semimembranosus are the most injured hamstring muscles. The mechanism of action is typically an eccentric contraction for the biceps femoris and a stretch for the semimembranosus. Furthermore, during sprinting, the biarticular hamstrings act simultaneously as hip extensors and knee flexors, making them vulnerable to injury.

The hamstrings contract concentrically after a foot strike, and an injury is less likely to occur during this gait cycle phase. However, they contract eccentrically during the late swing and stance phases, increasing the injury risk. There is a higher risk during the late swing phase than the late stance phase because of the lengthened position of the hamstring muscles(3).

The long head of the biceps femoris experiences the highest amount of elongation and eccentric contraction during sprinting in the late swing phase(4). Furthermore, fatigue compounds the risk during all physical activities, particularly when the sport demands high eccentric capacity.

When an athlete kicks or picks the ball up from the floor while running, they place the leg in hip flexion and knee extension, stretching the hamstrings. This increases the injury risk in two ways. The first is through the lengthening or over-stretching of the muscle. The second is through the speed at which this dynamic change of position occurs. This happens particularly during deceleration.

Clinicians must be aware of the most frequent mechanisms of action associated with each sport. This knowledge will improve the subjective assessment and help to identify the correct management strategy for each injury. For example, dance injuries are mostly stretch-type and affect the semimembranosus(5). Whereas, kicking and running sports mainly result in acute strains. Although the management might be similar, the return to sport timeframes differ.

Table 1: Comparison of hamstring injuries during running and kicking

| Sport | Running | Kicking |

| Australian football | 80% | 18% |

| English rugby | 68% | 10% |

| English professional football | 60% |

Clinical Diagnosis

Clinicians must assess injuries thoroughly to ensure appropriate management. Hamstring injuries can be challenging to assess due to the multiple differential diagnoses surrounding the posterior thigh. There are subjective and objective clues that will help clinicians to identify the classification and injury type.

Subjective Clues

- Demands of the sport (e.g., sprinting and kicking vs. dancing).

- The mechanism of injury (e.g., acute strain during sprinting or kicking vs. a gradual onset during stretching movements).

Objective Clues

- Assessing gait (e.g., antalgic gait may indicate severity).

- Observing for bruising.

- Range of motion limitations

- Pain on palpation.

- Neurodynamic testing.

- Assessing for strength deficits through sequential muscle testing. For example:

- Standing hamstring curl - concentric.

- Double leg bridge – isometric, then concentric, into eccentric.

- Single-leg bridge – isometric, then concentric, into eccentric.

- Resisted open kinetic chain exercises – concentric, eccentric, and plyometric.

Clinicians must palpate thoroughly to locate the area of maximal tenderness. For injuries sustained during sprinting activities, they must palpate the long head of the biceps femoris. Clinicians must palpate the semimembranosus for those sustained during stretch-type activities or kicking. There might be a palpable muscle defect with a surrounding secondary spasm.

Re-injury Risk Factors

When returning athletes to sport, clinicians must address the relevant risk factors that may lead to re-injury. There are modifiable and non-modifiable factors that clinicians must consider when designing and implementing return-to-sport programs (see table 2).

Table 2: Risk factors for hamstring injury and recurrence

| Modifiable | Non-modifiable |

| Shortened optimal muscle length and lack of muscle flexibility | Muscle composition |

| Muscle strength imbalances | Age |

| Insufficient warm-up | Previous injury |

| Fatigue | |

| Low back injury | |

| Increased dynamic anterior pelvic tilt (APT) | |

| Abnormal neural tension |

How to decrease anterior pelvic tilt

- Active lumbopelvic mobility.

- Hip flexor muscle flexibility.

- Hamstring muscle flexibility.

- Foam rolling.

- Hip extensor (gluteus maximus and hamstring focused) strengthening exercises.

- Specific lumbopelvic neuromuscular control training exercises and drills emphasizing posterior pelvic tilt.

- Manual therapy.

- Soft tissue mobilization.

- Lumbopelvic joint mobilization.

Non-modifiable

Muscle fibres

Athletes with a higher percentage of type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers are more prone to muscle strain injury than those with more type I (slow-twitch) muscle fibers.

Age

Hamstring injuries are more common after the age of 23.

Previous injury

A history of hamstring strain injury is a significant risk factor for a recurrence.

Conclusion

References

- Journal of Sport and Health Science 1 (2012) 92e101

- www.sportsinjurybulletin.com/diagnose--treat/hamstring-or-not-nerve-entrapment-and-posterior-thigh-pain

- Journal of Sports Sciences (2020) doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1845439

- Human Movement Science 66 (2019) 459-466

- BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 21 (2020) 641

- Journal of Sport and Health Science 6 (2017) 130-132

- Journal of Sports Medicine (2014) Article ID 127471, 8 pages

- Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 16 (2010) 6, 669–675

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.