You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Identifying exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction in the breathless athlete

Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction

Historically, athletes who presented with exertional dyspnea, with or without stridor, were thought to be asthmatic. When asthma treatments didn’t help, the breathlessness was attributed to “hysterical croup in women” or “Munchausen stridor,” which indicated a psychological component to the malady(1). It wasn’t until the 1960s that fiber-optic endoscopy enabled physicians to visualize the larynx.After 20 years of study, researchers reported that vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) during exercise could mimic asthma symptoms. By the 1990s, advances in technology allowed physicians to observe the larynx immediately after exercise and get a glimpse of how it responded during extreme activity. Today, physicians can perform continuous laryngoscopy during exercise on a treadmill, bike, or even while swimming. The ability to visualize laryngeal function in real time increased the understanding that exercise induced breathlessness may be caused by more than VCD. Thus, the more accurate name of exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) is now used to describe this syndrome.

Anatomy

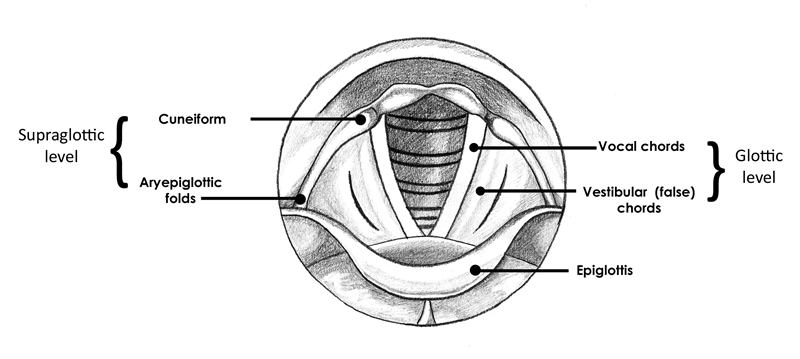

The larynx, also known as the ‘voice box,' sits at the front of the neck just behind the infra hyoid muscles, inferior to the pharynx and superior to the trachea. The larynx consists of large pieces of cartilage, called the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, and the epiglottis, that form the structure of the larynx. Smaller paired cartilages, called the arytenoid, corniculate and cuneiform cartilages exist within the larynx (see figure 1).Figure 1: Anatomy of the larynx

Breathing occurs unimpeded when the vocal cords abduct and the larynx is fully open. When partially closed, air passes over the vocal cords and results in phonation, or vocalization. The larynx closes the airway completely using the epiglottis to prevent entry of anything traveling from the mouth to the esophagus during swallowing. The larynx also produces cough to clear the airway.

Presentation

The typical athlete with EILO is an adolescent female under the age of 20. Studies show a prevalence of EILO in about 6% of this population(1). Symptoms occur only during exercise, with complaints of difficulty breathing, chest pain, throat tightness or discomfort, tingling in extremities, and an inspiratory wheeze. Symptoms usually resolve soon after stopping exercise.The larynx assists in respiration by remaining open. When functioning normally during exercise, the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles abduct the vocal folds and maximize the opening, thus allowing as much air as possible to pass through the airway. With EILO, the laryngeal inlet narrows during intensive exercise, when it should be open for maximal air intake. This can occur at the supraglottic level or the glottic level (see figure 1).

Some suspect that supraglottic narrowing occurs due to the negative pressure brought on by increased exertion and ventilation(1). The supraglottic structures – the arytenoid and aryepiglottic mucosa - may not have the rigidity to overcome the increasing negative pressure and passively collapse into the airway. At the glottic level, the vocal folds abnormally adduct and cover the laryngeal inlet.

Another hypothesis is that inflammation and neuromuscular defects contribute to the decreased integrity of the laryngeal structures. Muscles may be weak and therefore unable to maintain the open airway. Increased muscle tone in key muscles can offset the balance around the laryngeal inlet. Differences in muscle strength on each side of the larynx can also affect the opening.

Certain behavioral tendencies have been noted in athletes with EILO. The relationships between high-achieving perfectionist leanings, anxiety, and EILO are not well understood. It may simply be an association, as many athletes tend to be high achievers, and breathlessness tends to cause anxiety.

Investigators are also unclear as to why EILO seems to resolve with age. Many suspect that the decrease in symptoms comes as a result of lifestyle changes(1). As people age, they typically exercise less intensely.

Diagnosis

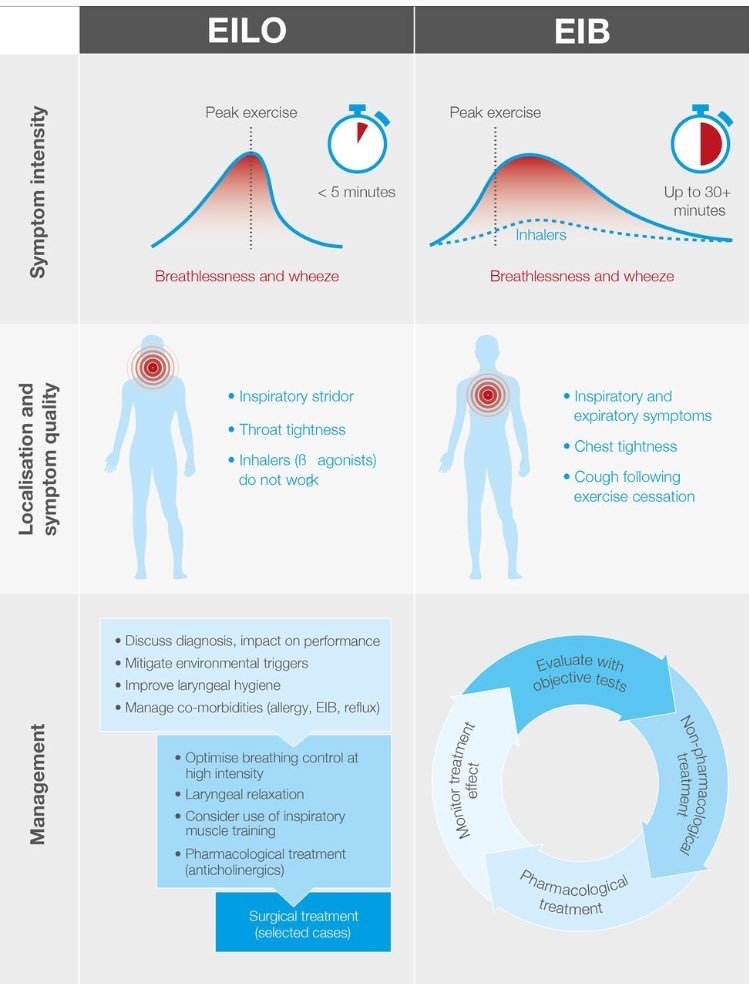

As mentioned, practitioners often assume breathlessness in athletes is caused by bronchoconstriction. However, there are key differences in the clinical presentation of EILO and asthma (see figure 2). Foremost is the fact that EILO occurs within minutes of peak exertion, whereas, asthma becomes symptomatic after stopping exercise. Conversely, EILO symptoms resolve quickly after stopping exercise, and bronchoconstriction continues up to 30 minutes after activity. Athletes with EILO demonstrate a wheeze on inspiration while asthmatics typically wheeze on expiration. When experiencing EILO, athletes complain of tightness in their throat and neck; asthmatics complain of tightness in their chest.In most instances, inhaled bronchodilators do not improve EILO symptoms. However, there is a sub population that gets some relief from these medications. One study found that in a cohort of athletes with exercise induced asthma, over 10% of them had coexisting EILO(2). This may confound a diagnosis and result in only partial treatment and thus increased frustration on the part of the athlete. Further complicating the clinical picture, triggers besides exercise such as stress, cold air, odors and allergies exist for both disorders.

Figure 2: Comparing exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction to exercise-induced bronchoconstriction(3)*

*used with permission

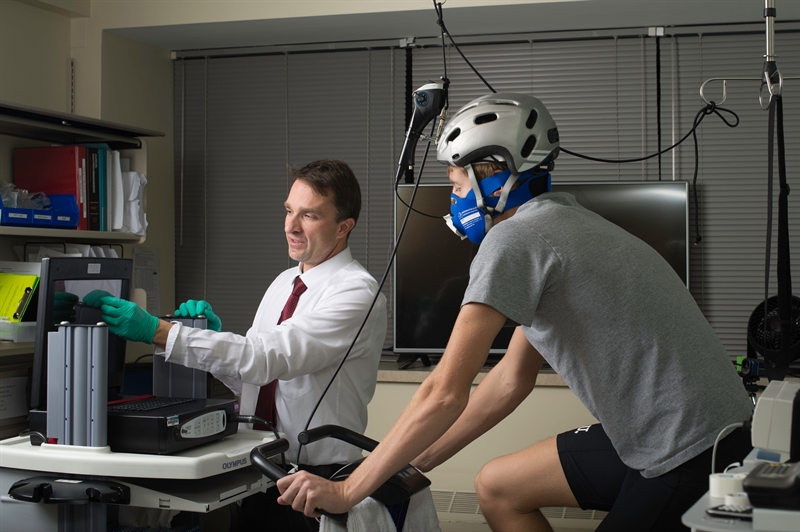

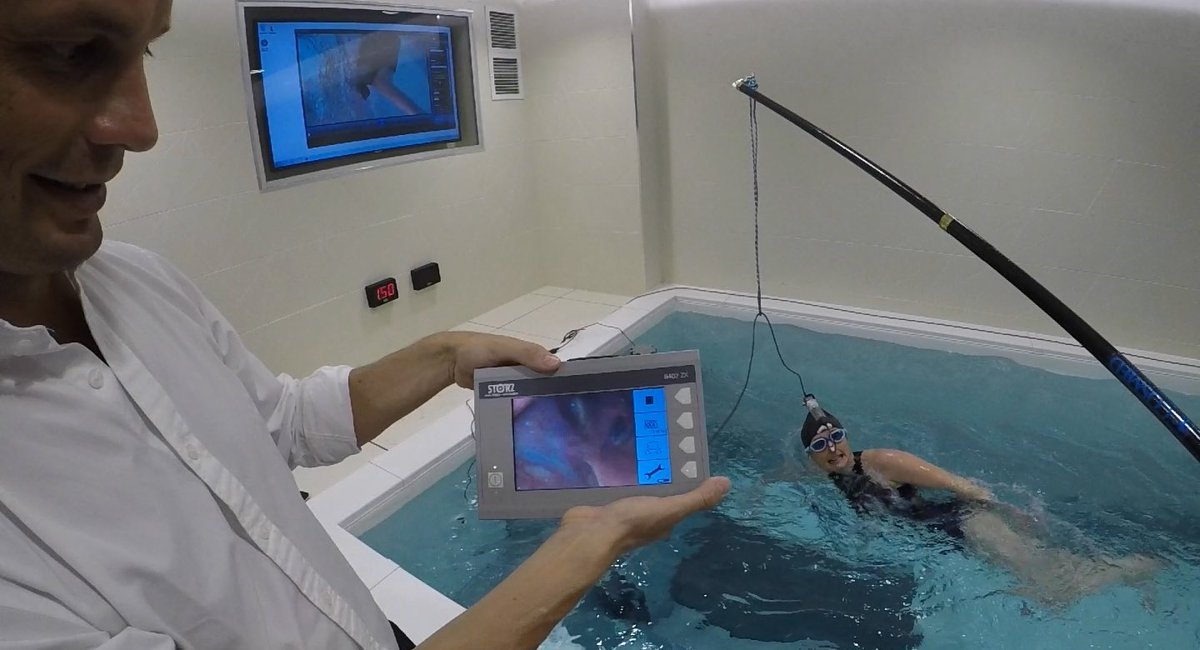

Physicians can make a definitive diagnosis by administering a continuous laryngoscopy exercise (CLE) test (see figures 3 and 4). This test allows for visualization of the larynx and vocal chords during exertion. To perform the test, an athlete exercises with a flexible laryngoscope inserted through their nasal passage. The scope’s camera enables both the physician and athlete to see what happens at the larynx when symptoms occur.

Figure 3: Continuous laryngoscopy exercise (CLE) test on a stationary bike*

*Photo credit Beth Woods, National Jewish Health. Used with permission.

Figure 4: Continuous laryngoscopy exercise (CLE) test while swimming(4)*

*used with permission

Treatment

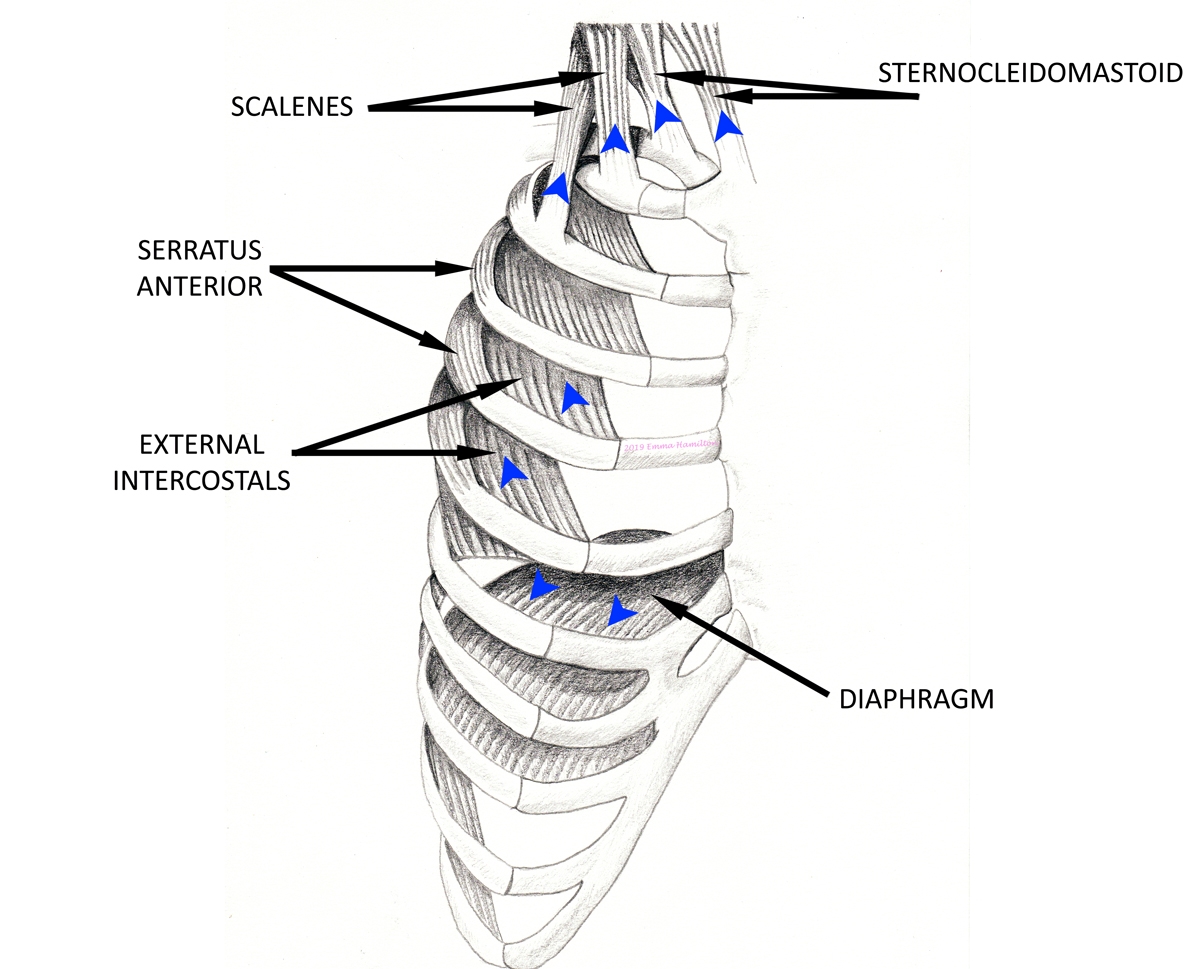

Proper diagnosis goes a long way toward resolving EILO. Knowing that the issue isn’t just in their heads relieves the stress and frustration many athletes feel. Medical evaluation should firstly include an exploration of possible laryngeal irritants such as reflux or sinus/nasal related maladies. Secondly, eliminate the possibility that EILO may co-exist with exercise-induced asthma. If the athlete tests negatively for coexisting medical issues, then pharmacological treatment is not usually warranted.Most athletes experience success with a conservative treatment approach including physio and speech therapy. Respiratory training should focus on diaphragmatic breathing and strengthening the primary inspiratory muscles in the lower chest (see figure 5). The overuse of the accessory muscles in the neck on inspiration may contribute to feelings of tightness in the throat. Emphasis on nasal breathing increases the humidity in inspired air and decreases laryngeal irritation.

Figure 5: Muscles of inspiration

Because both nasal and abdominal breathing are difficult to maintain during peak exertion, a team at National Jewish Health in Denver pioneered additional techniques for athletes to use when exercising(5). These breathing strategies promote relaxation of the throat and increase the opening of the airway. They involve three methods, known collectively as the Olin Exercise-Induced Laryngeal Obstruction Biphasic Inspiration (EILOBI) techniques. The premise of this approach, developed under therapeutic laryngoscopy during exercise (TLE), is the observed benefit of biphasic inspiration. That is, when observing athletes with EILO during exertion, researchers found that a brief period of high resistance inspiration followed by relaxed low resistance inspiration through the mouth, helped widen the opening of the airway.

Various methods were developed to achieve this high resistance to low resistance inhalation. In the “tongue variant” exercise, athletes breathe in through the nose and then through the open mouth; the “tooth variant” requires the athlete to breathe forcibly through the teeth at the beginning of the breath and then open the mouth to breathe freely; lastly, the “lip variant” begins each breath with pursed lips as if breathing through a straw, then completes the inspiration with a relaxed open mouth.

Athletes should practice all respiratory exercises with a physio or speech therapist under relaxed non-exertional conditions before attempting during exercise. The use of therapeutic TLE provides feedback during exertion, which helps athletes master the Olin EILOBI techniques. Learning under clinical conditions allows the athlete to feel in control when symptoms of EILO arise on the field. Additional conservative measures include maintaining laryngeal health by refraining from smoking and caffeine, reducing stress, and staying hydrated.

When conservative measures fail, the athlete may consider surgical options. Laser surgery corrects overly large structures that may contribute to EILO. This is usually an option of last resort, and little research exists as to the efficacy of surgical intervention(2).

Practical implications

- Take any complaints of difficulty breathing when exercising seriously.

- If unable to reproduce symptoms in the clinic, have an athlete take a ‘selfie’ video when symptoms occur. Listen for dysphonia, inspiratory wheeze, and swift resolution of symptoms after stopping exercise.

- Suspected EILO should be referred for diagnostic confirmation and evaluation of co-morbid factors such as reflux and sinus/nasal dysfunction.

- Most athletes with EILO respond positively to conservative treatment including respiratory muscle training and institution of breathing strategies during exertion.

References

- Immune Allergy Clin North Am. 2018 May;38(2):271-280

- Br J Gen Pract.2016 Sep;66(650):e683-5

- Br J Sports Med. 2019;53;616-17

- 2017 Oct;127:2298-2301

- J Voice. 2018 Nov;32(6):698-704

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.