Cyclops lesions after ACL reconstruction: something to keep an eye on

First described in 1990 by Jackson and Schaefer(1), a cyclops lesion is a reasonably common complication following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR), with the majority being benign and asymptomatic(2). These lesions can also develop in knees that have had ACL injury without a reconstruction(3). These nodes lead to a loss of terminal extension, ongoing anterior knee pain, and altered gait and landing mechanics.

Cyclops lesion anatomy

The term ‘cyclops lesion’ comes from the arthroscopic appearance of the lesion, which resembles an eye. Seen as an ovoid-shaped mass with venous vessels in the center(1), these lesions are usually found in the femur’s intercondylar notch(4,5). They occur in an estimated 10-25% of knees after ACLR(5,6).Lesions typically form within the first six months post-ACLR surgery and remain fairly constant in size over the two years following surgery. Lesions have an average size of 14mm x 8mm and result in a loss of about 19 degrees of extension(5). They consist of a fibrovascular nodule of tissue that forms anterolateral to the tibial tunnel of the ACLR graft. Fibrous with a dense proliferation of vessels, the lesions are either hard and comprised of bone tissue(1,5), or soft and made of fibrocartilage. The latter is called a cyclopoid lesion(5). Their occurrence does not correlate with an athlete’s age, sex, the time between injury and surgery, or the type of graft fixation (patella versus hamstring graft)(6-8).

Whether the lesion is hard or soft may determine whether a patient loses range of movement in knee extension. The size of the node also affects the incidence of mechanical symptoms. Cyclops syndrome occurs if the lesion causes a loss of terminal extension due to an impingement at the intercondylar notch(1,5,9,10). This loss of extension range, theoretically caused more often by hard lesions, can be as great as 30º(9-11). However, the differential diagnosis must include other reasons for a loss of extension following ACLR like(12):

- Reflex inhibition due to joint effusion.

- Excessively anterior tibial tunnel placement.

- Fixation of the graft at high knee flexion angles.

- Generalized arthrofibrosis.

Etiology of cyclops lesions

Several factors contribute to the development of cyclops lesions(9,13):- Bone debris from drilling during the ACLR.

- Anteriorly positioned graft.

- ACL stump remnants.

- Partially torn anterior graft fibers.

- Graft hypertrophy from impingement.

Wang and Yingfang proposed that the lesion may develop due to an aggressive inflammatory process started at the graft site of biologic grafts following surgery(14). Research reveals the incidence is very low (2.5%) in those who receive a non-biologic graft, such as a Leeds-Keio prosthesis, thus supporting this hypothesis(15). However, non-biologic grafts also share similar risks as biologic grafts, such as bone debris and less than optimal graft placement.

Most cyclops lesions occur in single bundle grafts. The lesion’s location in single bundle grafts is near the tibial tunnel, anterior to the reconstructed graft, in the front of the intercondylar notch, or from the tibial tunnel to the graft. In all instances, however, the cyclops lesion will adhere to the graft(4). Interestingly, in double-bundle grafts, the cyclops is found on the roof of the intercondylar notch(16).

Signs and symptoms

The primary complaint of an athlete suffering from cyclops syndrome is a loss of knee extension with catching and snapping during walking(16). The patient may also feel or hear a ‘clunk’ with or without pain during terminal extension(12). A study at the University of California showed that patients with a cyclops lesion demonstrate altered gait mechanics(17). These patients possessed sagittal plane loading patterns, which are different when compared to ACLR patients without a cyclops lesion. The changed way of walking places higher peak loads on the knee, possibly leading to medial joint cartilage degeneration and early-onset osteoarthritis.Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers the best diagnostic test for cyclops lesions with a sensitivity of 85%, a specificity of 84.6%, and accuracy of 84.8%(18,19). Lesions appear as well visualized nodules with a convex anterior border. On T1-weighted images, they appear with low to intermediate signal intensity. On ultrasound, they present as a soft tissue mass within the intercondylar notch that has heterogenous hypo-echogenicity and hyperemia(13).Management of cyclops lesions

Unfortunately for the clinician, a symptomatic cyclops lesion causing loss of terminal extension – with or without a painful clunk – cannot be rehabilitated. Instead, management consists of surgical debridement via arthroscopy followed by intensive physiotherapy to maintain the regained knee extension.However, some suggest the most significant risk factor for developing an obstructive cyclops lesion is the failure to regain full extension in the early postoperative period(2,20). The extension deficit at this early stage is likely due to autogenic muscle inhibition (AMI)(21). This phenomenon is a reflex loop whereby the articular receptors are discharged due to pain, inflammation, and capsular distention. This cycle leads to central nervous system-mediated changes in hamstring muscle tension and quadriceps deactivation(22).

The theory holds that if this reflex cycle becomes established, the limited range may give space for the cyclops lesion to form and eventually mechanically block extension. Therefore, clinicians should focus on regaining terminal extension and breaking the AMI cycle by minimizing effusion following ACLR surgery as quickly as possible (see box 1).

Box 1: The importance of removing effusions

Knee joint effusion is a result of an intra-articular pathology which triggers the synovial membrane to secrete excessive synovial fluid. Otherwise known as joint swelling, the excess fluid is the body’s attempt to remove any offending intra-articular debris.The presence of an effusion is problematic for both the clinician and the athlete. Small volumes of excess fluid (as little as 20mls to 30mls) increase the pressure within the joint and inhibit muscle function by 50% to 60%(23-26). Furthermore, swelling alters the knee joint mechanics during landing tasks(27). Individuals with a knee effusion experience greater ground reaction forces and greater knee extension on landing, resulting in more force transferred to the knee joint and its passive restraints.

Ways to manage and remove effusions include:

- Assess the knee for effusions regularly, especially before loading. If the load is new or progressive, monitor the knee joint for the next 24 hours.

- Remove the effusion if present. Conventional methods include elevation, compression with donut felt, effusion massage, and limited weight-bearing. Recommend medically-directed interventions such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs) or direct needle aspiration if indicated. Removing the internal fluid will significantly reduce the internal pressure within the knee and improve quadriceps strength.

- Select appropriate exercises, like quadriceps exercises performed in positions of partial (20°) knee flexion or isometric squats in 20-30° flexion. These exercises allow muscle recruitment without increasing the intra-articular pressure associated with full knee extension.

- Early pool work also provides hydrostatic pressure to aid with effusion drainage.

Regaining knee extension

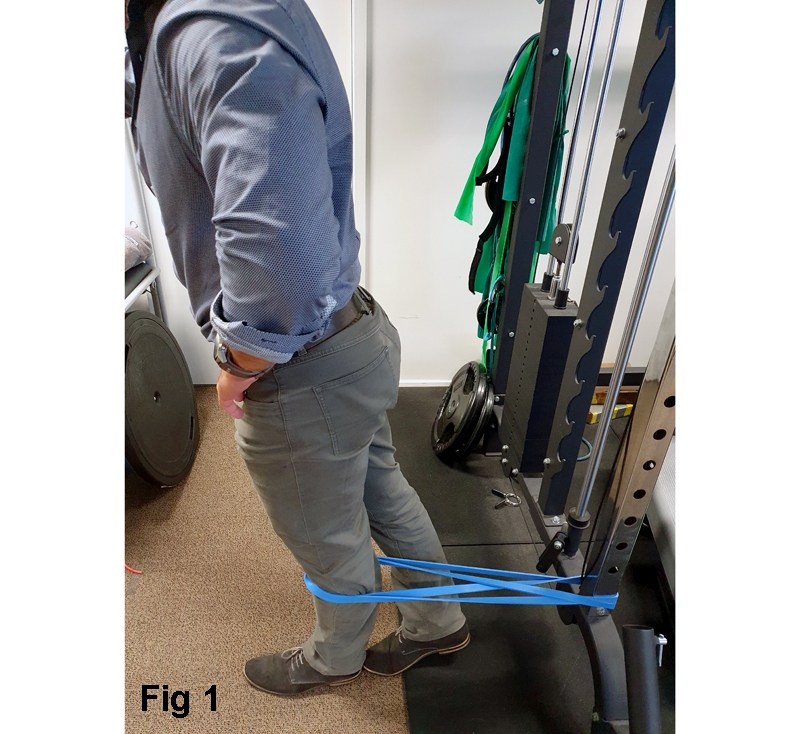

There are many ways that clinicians can attempt to regain knee extension following ACLR. These consist of a mix of passive stretching methods, soft tissue massage to the posterior muscles such as hamstrings, popliteus and gastrocnemius, and active quadriceps exercises to facilitate knee extension (see figures 1 and 2).Figures 1 and 2: Regaining extension via stretching and resisted quadriceps activation

- Wrap a strong elastic resistance band around the shin (band pulling backward – see figure 1). Place the band on the shin and not the thigh to create a relative posterior shear effect to the knee (ACLR protective).

- Step forward so that the band takes up the stretch. Allow the band to create an extension effect for 1 minute. Place the other foot behind the heel to prevent the heel sliding.

- Turn around and wrap the bad around the posterior thigh (band pulling forwards – see figure 2). This also creates a posterior shear effect.

- Step backward to increase the thigh band tension. Now perform 15 repetitions of knee extension movements. Place the other foot in front to prevent the foot sliding.

- Continue this for as many rounds as desired.

Summary

Cyclops lesions are reasonably common, usually occurring as a benign consequence of a biologic ACLR. If they form a hard and large mass, they may eventually block knee extension in the six months following ACLR causing pain, discomfort, and altered knee mechanics with gait and landing movements. A keen clinician will recognize them when terminal extension remains resistant. Help athletes avoid suffering a lesion that limits extension by actively working to regain early extension and reducing any the effusion.References

- 1990;6(3):171-178

- The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;48(3):565–572

- Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007; 15:144--146

- 2009; 25:626–631

- Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 1999; 7:284–289

- European Radiology. 2016:1–10

- Eur Radiol. 2017 August ; 27(8): 3499–3508

- Current Orthopaedic Practice. 31(1). 36-40

- 1992;8(1):10-18

- 1998;14:869-876

- Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2014. 22:1090–1096

- Current Orthopaedic Practice. 2011, 22(4). 327-332

- J of Chiro Med. 15(3). 214-217

- Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, 2009. 25(6), 2009: 626-631

- Knee Surg, Sports Traumatol, Arthroscopy, 1992. 2: 76-79

- Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. 2010. 26(11), 1483-1488

- J Orthop Res. 2017 October ; 35(10): 2275–2281

- AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000, 174:719–726

- Skelet Radiol. 2012. 41:997–1002

- Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(1)

- Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 1993. 52: 829-834

- Ortho Res. 2011;29(9):1383-1389

- The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 1988. 70-B(4): p. 635- 638

- Journal of Athletic Training, 2010. 45(1): p. 87-97. 3

- Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology, 1988. 73: p. 305-314

- Clinical Physiology. 1990. 10(5): p. 489-500

- American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007. 35(8): 1269-1275

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.