You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Cervicogenic headaches: a pain in the neck

Headaches are an extremely common pain disorder affecting 66% of the general population, and causing widespread changes to quality of life and work productivityJ Man & Man Th. 2008. 16 (2): 73-80. A list of fourteen different headache forms have been documented by The International Headache SocietyCephalalgia. 2013. 33(9): 629-808. In particular, its classification of headache disorders can be extremely useful when diagnosing a cause of headache (see Box 1).

| Box 1: IHS classification of headache disorders (2013) |

|---|

| -Primary — Headache without apparent identifiable cause — Examples: tension-type headache (TTH), migraine, chronic daily headache, medication overuse headache, Trigeminal autonomic cephalagia (eg cluster headache) |

| -Secondary — Headache associated with secondary pathology — Examples: CGH, talomandibular joint (TMJ), infection, brain tumour, stroke |

| -Cranial neuropathies, other facial pains and other headaches — Headache related to neural disorders of the head and neck, eg trigeminal neuralgia |

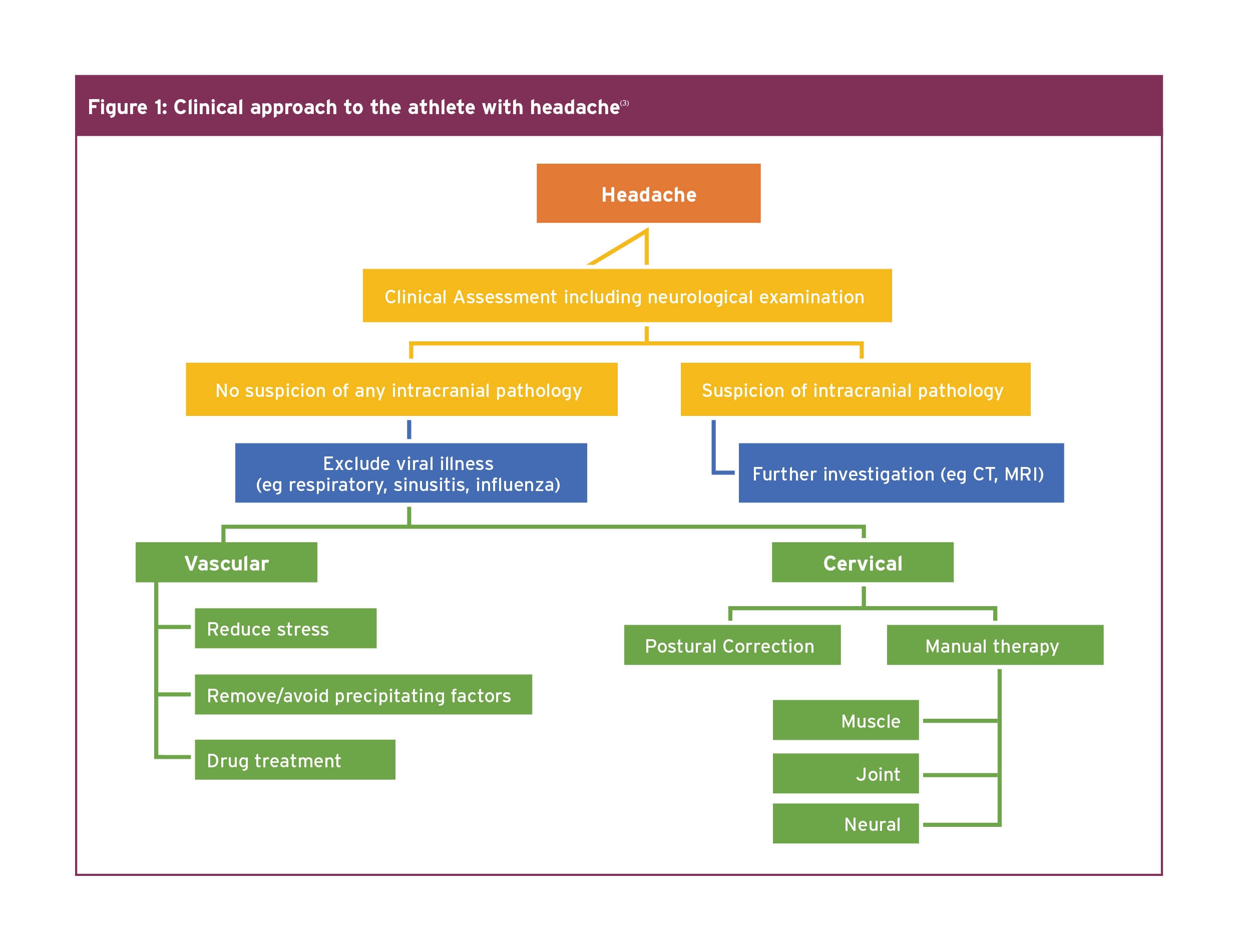

Since each form of headache has a different pathological basis and because an incorrect differential diagnosis will often lead to treatment failure, it is critical to correctly diagnose the type of headache. This is of particular importance for manual therapy interventions, as otherwise, they are unlikely to be effective for the majority of headache formsCephalalgia. 2013. 33(9): 629-808. When considering the best clinical approach to athletes complaining of headache, there is a helpful tool, which can be used when contemplating the appropriate management pathway (see Figure 1).

The role of trigeminocervical nucleus (TCN)

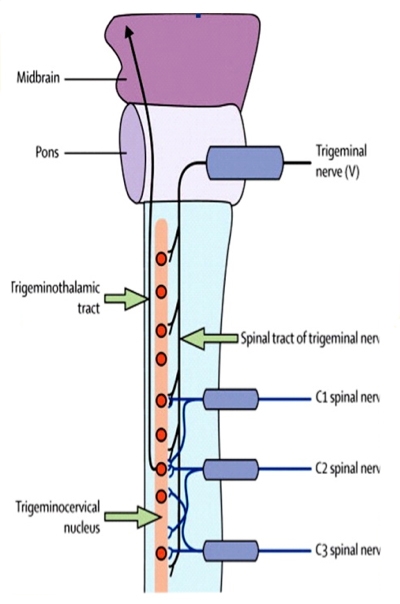

The most common form of headache is TTH with a global prevalence of 38%; this compares with migraine, which has a prevalence of 10%, chronic daily headache 3%, and CGH 2.5-4.1%J Man & Man Th. 2008. 16 (2): 73-80. CGH arises primarily from a musculoskeletal dysfunction in the upper three cervical segments. The prevalence is as high as 53% in patients or athletes with headache after whiplash-type traumaLancet Neurol 2009. 8: 959-68.The mechanism underlying the pain involves convergence between cervical and trigeminal afferents in the TCN, which descends in the spinal cord to the level of C3/4 (see Figure 2)Lancet Neurol 2009. 8: 959-68 Cephalalgia. 2011 Jun; 31 (8):953-63.

The TCN has anatomical and functional continuity with the dorsal grey columns of these spinal segments. Hence, input via sensory afferents, principally from any of the upper three cervical nerve roots, may mistakenly be perceived as pain in the head, a concept known as convergenceJ Man & Man Th. 2008. 16 (2): 73-80 Cephalalgia. 2011 Jun; 31 (8):953-63.

Convergence between cervical afferents allows for upper cervical pain to be referred to regions of the head innervated by cervical nerves (occipital and auricular regions). However, convergence with trigeminal afferents allows for referral into parietal, frontal, and orbital regionsLancet Neurol 2009. 8: 959-68. This can cause confusion when diagnosing the cause of headaches.

Differentiating headaches

It can be confusing distinguishing between different headaches clinically. The subjective information is very important.The following diagnostic criteria have been proposed by Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group (see Box 2)Headache. 1998. 38: 442-445. Diagnosis is based on these subjective features, as well as a physical examination of articular, neural, and myogenic systems, while understanding the mechanisms of symptoms. Exclusion of red and yellow flags at this stage is, also, very important. There can be many structural causes of CGH (see Box 3).

| Box 2: CGH diagnostic criteria | |

|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms of neckinvolvement | Precipitation of headache by: - Neck movement - Postural changes &/or - Pressure over the upper cervical/ occipital region Restriction of neck ROM Ipsilateral neck, shoulder, or vague arm pain |

| Head pain characteristics | - Moderate-severe, non-throbbing, non-clustering. Starts in the neck, spreads to the head. - Varying duration, usually last longer than migraine headache. - Long-term fluctuating pattern, becoming continuous when chronic. |

| Migraines | - More likely to be female - Report nausea, photophobia, and throbbing pain. - Follow a crescendo pattern. |

| Box 3: Potential causes of CGHJ Man & Man Th. 2008. 16 (2): 73-80 |

|---|

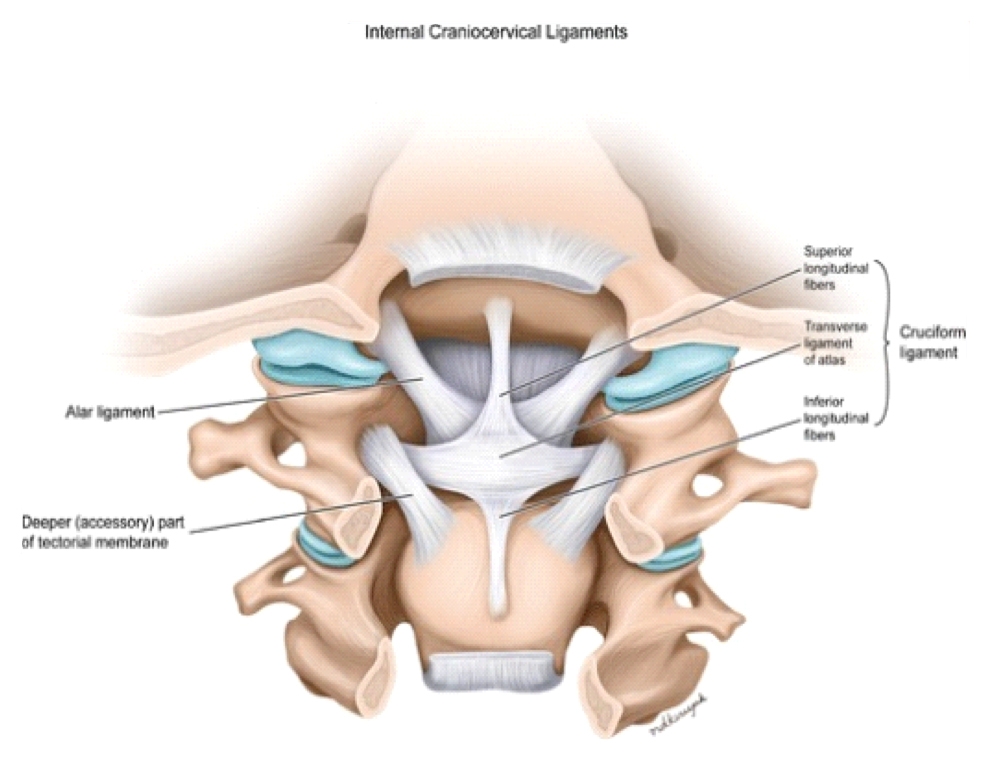

| Joints C0-4 — Eg Sub-chondral bone, ligaments, capsules, intra and extra-articular soft tissues. |

| Muscles — Eg Upper trapezius, semispinalis, splenius, longissimus capitis, sternocleidomastoid, levator scapulae. |

| Neural structures — Eg Cervical dura, spinal nerves C1-3 (Greater and lesser occipital/ Third occipital nerves). |

| Others — Eg Temporomandibular joint |

| Psychosocial co-morbidities — Eg Depression, anxiety. |

| Vascular structures — Eg Vertebral and carotid arteries. |

Assessing for CGH

The goal of examination is to reproduce the pain of headache from cervical structures, with evidence of associated dysfunction. We can be confident that by assessing the articular, neural, and muscular structures during the examination, the source of CGH can be found. Subsequently, if pain cannot be reproduced, then cervical spine involvement can be ruled out, and other causes of headaches will need to be explored further.The prevalence of neural tissue pain disorders has been reported as between 7-10% of patients with CGHJ Man & Man Th. 2008. 16 (2): 73-80. Pain reproduction can be used as a tool to distinguish neural tissue involvement when evaluating posture, upper cervical active ROM, neural provocation tests combined with upper cervical ROM, nerve palpation (greater, lesser and third occipital nerves), and neurological examination. Likewise, if there is any suspicion of vascular involvement, a clinical framework has been proposed providing an accurate guideline for assessment and managementManual Th. 2014. 19: 222-228. This article however will focus solely on the assessment and treatment of CGH with articular cause. Trauma involving forced cervical flexion, rotation, or side flexion is very common in sport. Similar to testing ligament stability in the knee joint following trauma , screening for craniovertebral instability should be common-place in the assessment – details of which are shown below.

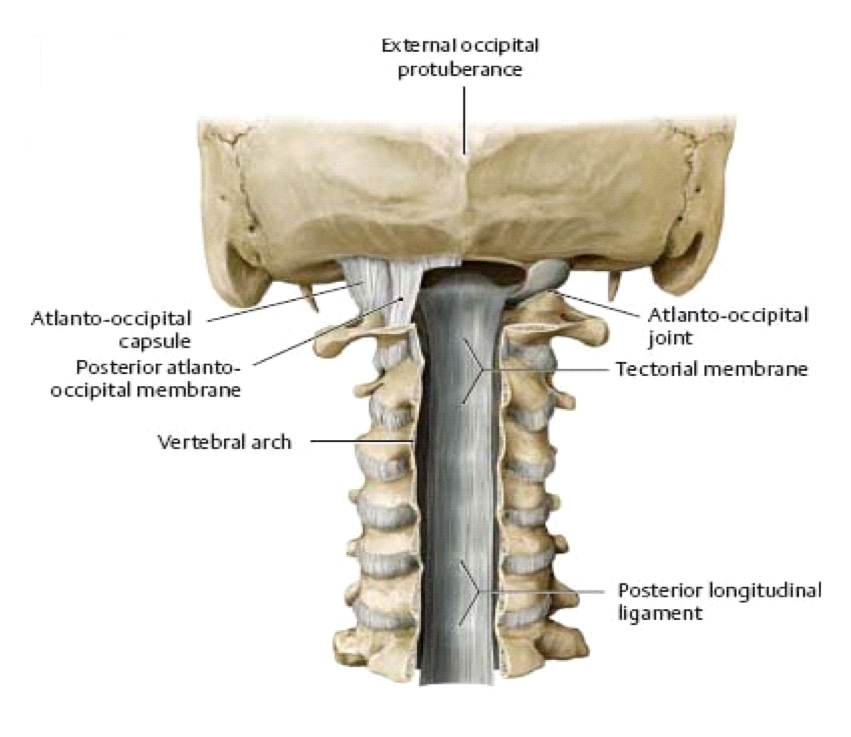

Screening for craniovertebral instability

(Note that while these tests are appropriate for diagnosing cervical instability, clinicians should be aware that there may be other cervical-related issues that can cause pain – eg ‘grumpy’ facet joints – and should assess accordingly.)The Sharp Purser (transverse ligament) test

The tectorial membrane (posterior longitudinal ligament) test

Alar ligament test

Flexion/rotation

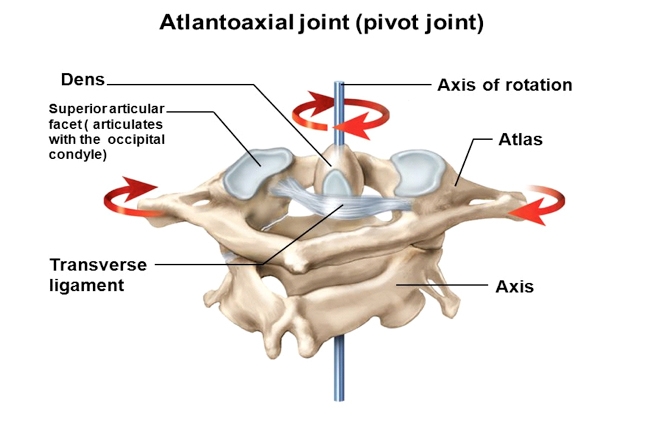

The C1-2 motion segment accounts for 50% of the rotation in the cervical spine. Thus, pain arising from an impairment of this segment is a frequent finding in individuals with CGHJOSPT. 2010. 40(4): 225-229. The flexion-rotation test (FRT) is an easily applied clinical test biased to assess dysfunction at the C1-2 motion segmentJOSPT. 2010. 40(4): 225-229. Average FRT ROM in healthy individuals is 44 degrees. The test is positive if there is pain or restriction of 10degrees in ROM on either side.The flexion-rotation test

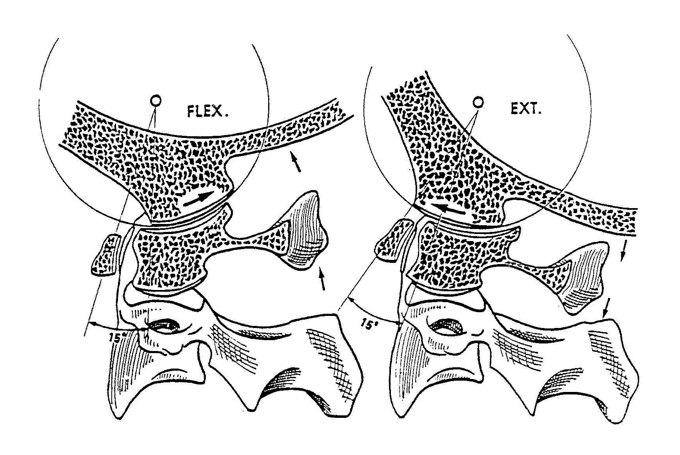

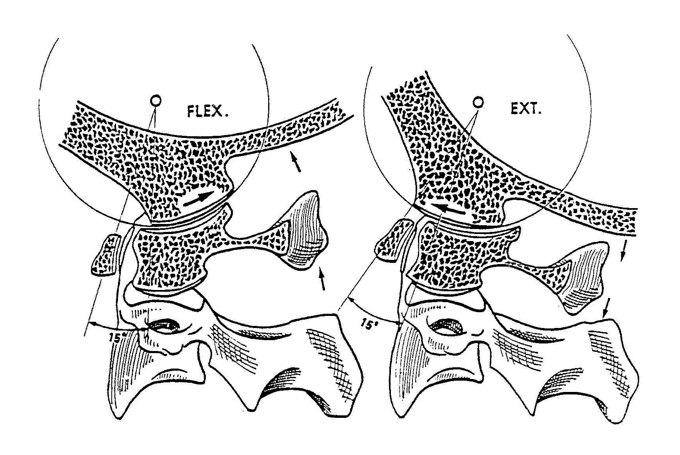

Due to the lack of intervertebral disc and altered biomechanics of the high cervical spine, combined movements are assessed differently. The primary movement available at C0-1 is flexion (3 degrees) and extension, with the majority of movement occurring in extension (21 degrees). As a result of the sliding movement of the occipital condyles, flexion will stress the posterior capsules on the right and the left at C0-1. The addition of ipsi-lateral rotation will further stress the posterior capsule on the same side. This can be a nice diagnostic tool for assessing the involvement of C0-1 (see below).

In contrast, upper cervical extension will stress the anterior capsules of C0-1. The addition of contra-lateral rotation will further stress the anterior capsule on the opposite side of the movement (see C0-1 extension/rotation test below). These tests should rule out C0-2 involvement. It should be validated with passive physiological intervertebral movements (PPIVMs), and passive accessory intervertebral movements (PAIVMs) to isolate the problematic segment. These can also be effective treatment tools if appropriate. Treating headaches associated with neck pain There is supportive evidence to suggest that manual therapies are effective for CGH – particularly spinal manipulation and mobilisation with exercise. This is especially true for cranio-cervical muscle strengthening, and scapula positional re-trainingJ Man & Man Th. 2008. 16 (2): 73-80 Chiro & Osteo. 2010. 18(3): 1-33 J Man & Man Th. 2014. 22(1): 44-50 SPINE. 2002. 27(17): 1835-1843 Cephalalgia. 2016. 36(5): 474-92 J Pain. 2005. 6(10): 700-703. However, evidence is less supportive for the effect of manual therapy on headaches associated with migraineCephalalgia. 2016. 36(5): 474-92 J Pain. 2005. 6(10): 700-703. Here, we will explore some of the most effective manual therapy techniques for CGH.

C0-1 flexion/ rotation assessment

Pain at the time: Headache sustained natural apophyseal glide (SNAG)

C0-1 extension/ rotation test

Intermittent pain: C1-2 self-SNAG

If we suspect TCN sensitisation, evidence suggests that better management of sleep, stress and anxietyPLOS ONE. 2014. 9(8): 1-14, as well as dietJ Headache Pain. 2013. 14(1): 010, and moderate intensity exerciseCephalalgia. 2016. 36(5): 474 92 Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013. 17(12): 1-6 is beneficial. A ‘bucket analogy’ can be described to help athletes understand the concept of TCN sensitisation. When the TCN is overloaded with information, this compares to a bucket being overfilled with water. When the TCN is bombarded by too much information, a headache is the by-product, or the bucket overflows. If an athlete can control the level of information, they can control the level of TCN sensitisation.

The Mulligan Concept proposes two techniques to help with headachesJ Excer Rehab. 2014. 10(2): 131-5 JOSPT. 2007. 37(3): 100-107 Man Th. 2004. Wellington. One is for pain or headache that must be present ‘at the time’ of the treatment. Pain is necessary to determine whether the treatment is working. The other is for pain or headache that is ‘intermittent’ in nature.

Intermittent pain: C2-3 self-SNAG

Summary

Diagnosing the cause of headaches can be very difficult. There are many types of headaches, and many different causes. In order, the most common are TTH, Migraine and CGH. In particular the sensitisation of TCN is a significant contributor, which must be considered when formalising a treatment plan.Treatment relies on the diagnostic cri teria, but where appropriate, physiotherapy can be beneficial to assess and treat if the cause is arthrogenic, neurogenic, and/or myogenic in nature. In particular, manual therapy, a small part of which is described in this article, has good evidence to support its foundation in treating and managing CGH. Before treatment however, always be aware of vascular involvement, and test for craniovertebral instability, particularly after trauma in sport.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.