The Flexor Hallucis Longus

The flexor hallucis longs (FHL) has been referred to as the ‘Achilles of the foot’ due to its unique role controlling mid foot pronation and supination. Its physiological and mechanical properties allow it to act as a powerful convertor of force from the rear foot all the way through to the big toe(1-4). Due to its anatomical arrangement and unique actions, this muscle-tendon unit that can become injured in athletic populations. Injury to the FHL, also known as ‘dancers tendonitis’ is prevalent in classic ballet dancers(1,2).However it happens to athletes in other sports that require repetitive push-off and extreme plantar flexion, such as swimmers, sprinters, footballers, and gymnasts. Moreover, it may also suffer damage following injury to the ankle and/or syndesmosis due to its close proximity to the talus and the ankle joint.

Relevant anatomy and biomechanics

The FHL originates from the posterior and distal two thirds of the fibula, the interosseous membrane of the leg and to the intermuscular septa(5). It is distal and lateral to the muscle belly of the flexor digitorum longus (FDL), and deep to the soleus and gastrocnemius. It is pennate in shape and the fibers of the muscle continue and converge on its tendon as it crosses the posterior surface of the lower tibia.Figure 1: FHL muscle (posterior view)

The FHL tendon then passes posterior to the talus and deep to the medial retinacular structures at the postero-medial ankle(1,2,6,7). It is enclosed within a synovial sheath and passes through a fibro-osseous tunnel between the medial retinaculum and the lateral tubercles of the talus. As it turns to course towards the arch, it sits below the sustentaculum tali, which forms a horizontal shealth of bone on the calcaneus. The FHL is therefore part of the tarsal tunnel, and within the tunnel, it lies posterior to the neurovascular bundle.

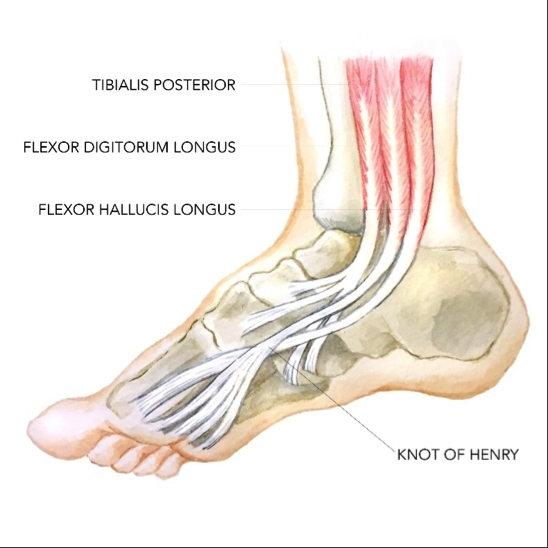

As the FHL tendon passes through the arch of the foot, it crosses over the tendon of the flexor digitorum longus (FDL) to lie on top of it. This is referred to as the ‘knot of Henry’(7). At the level of the Knot of Henry, the FHL is dorsal to the medial edge of the plantar fascia. The tendon continues between the two sesamoid bones of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint where it is covered by the inter-sesamoid ligament, and inserts at the base of the distal phalanx of the great toe(7).

Figure 2: FHL and the tendons of the FDL and tibialis posterior

The FHL therefore interacts with three retinacular structures (at the tarsal tunnel, Knot of Henry and inter-sesamoid ligament) and this has implications for creating abnormal constriction and stress on the tendon that then may lead to injury. The unique features of the FHL that make it an important muscle in midfoot and forefoot function are as follows(2):

- It passes under the sustentaculum tali, which provides a pulley system for the tendon to work from.

- It has a larger cross sectional area than FDL(8).

The primary functions of the FHL are:

- To act as a primary supinator of the subtalar joint. It does this by exerting an indirect upward pull on the talus via its direct abutment against the sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus. This action supinates and externally rotates the subtalar joint to pull the talus into the tibiofibular mortise. This creates a rigid rearfoot during toe off phase of gait.

- To lock the midtarsal joints - this enhances the stability at the medial longitudinal arch(9).

- To eccentrically controls pronation at the subtalar joint(9).

- As a primary active plantar flexor of the first MTP and interphalangeal (IP) joints of the great toe.

- To restrain passive dorsiflexion at the first MTP joint(7).

- As a secondary plantar flexor of the ankle. During plantarflexion, the FHL tendon becomes compressed within the fibro-osseous tunnel as the muscle contracts. In contrast, ankle dorsiflexion, causes the FHL to be stretched between the talar tubercles and sustentaculum tali(10).

- To operate isometrically during the gait cycle so that constant length is maintained throughout the muscle during the entire weight bearing phase of the gait cycle(11). This would be a similar mechanism to the Windlass mechanism of the plantar fascia. As the ankle plantarflexes during push-off, the big toe is flexing and this offsets the change in length caused by plantarflexion.

Differential diagnosis in FHL

Particular sports and athletic endeavours place a large load across the FHL and its tendon. For example, ballet dancers rely heavily on the FHL to enhance the dynamic stability of the foot. Classical ballet dancers assume particular postures that constantly stress the FHL tendon, such as pointe positions - on their tip toes whilst in ankle hyperplantarflexion and extreme dorsiflexion of the hallux. Overuse conditions in the FHL tendon can develop and tendinopathy may result(4).Those who complain of FHL tendon irritation, inflammation, tenosynovitis, partial tears and/or nodule formation often present with pain at the posterior or postero-medial ankle. However, the site of symptoms can be variable depending on the anatomic location of the tendon pathology. Heel pain (tarsal tunnel), plantar midfoot pain (knot of Henry), and first MTP joint pain (inter-sesamoid ligament) have all been reported(1, 7). Due to the proximity of the FHL tendon to more commonly injured structures, many differential diagnoses exist including:

- Posterior tibial tendon (medial ankle)

- Os trigonum (posterior ankle)

- Plantar fascia (plantar midfoot)

- First MTP joint (hallux rigidus)

- Achilles tendinopathy

While experts debate the exact cause of FHL injury, most believe that constriction occurs at the fibre-osseous tunnel in the posterior ankle in and around the tarsal tunnel, or the Knot of Henry in the mid foot or inter-sesamoid ligament. This pseudo-entrapment creates repetitive micro trauma, and this can lead to microscopic and macroscopic tissue damage(1,2,7,12). Although irritation can occur at the knot of Henry and between the sesamoids of the great toe, the most commonly irritated site is deep to the flexor retinaculum, where the tendon lies within the fibro-osseous tunnel(6).

Repeated irritation of the tendon’s sheath can cause hypertrophy of the tendon within this tunnel. Thickening or fibrosis can impede the normal gliding of the tendon, thus creating pain and movement limitations(13). Increased pain and decreased use can lead to weakness of the tendon and muscle. Adhesions and the development of calcific nodules may follow(14).

When the foot is fully plantarflexed, relative incongruity between the FHL and the fibro-osseous tunnel exists(1,2). This may cause abnormal stresses and resultant tenosynovitis to the FHL tendon. Injury at the level of the talus may also be due to an abrupt change in direction of the tendon at this level(15). Other possible causes may relate to a low-lying FHL muscle belly or an accessory FDL(16). Immunohistochemical studies on cadaveric tendons have identified avascular zones where the tendon wraps around the talus and where the tendon crosses the first metatarsal head(15). This may all be compounded by the high tensile loads imposed on the FHL tendon as a dancer/ athlete jumps and lands and absorbs shock through the foot and thus FHL tendon (10).

Although not usually a concern for the athlete, the tendon of the FHL may be ruptured, particularly in those suffering from rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This is due to the weakening of the tendon caused by the RA induced tenosynovitis. It has been found that in patients with a ruptured FHL, the hallux becomes rigid (hallux rigidus), resulting in associated erosion and joint damage at the 1stMTP joint(17).

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

*SubjectiveInjury to the FHL tendon is usually characterized by pain located posterior and inferior to the medial malleolus, made worse by jumping and landing. In particular, dance related moves such as a demi-relevé, dancing en pointe, demo-plié, grand plié, and pointing the foot also worsen the pain. The athlete may feel a sensation of crepitus in the tendon and triggering of the first toe depending on the severity of the tendon injury(6). Triggering may also involve an inability to relax the toe after full plantar flexion of the ankle when pointing the foot, resulting in a feeling of the first toe being stuck in flexion(1,2,6,7,10).

*Objective

Clinical examination of the foot and ankle in a dancer/athlete with a suspected FHL injury includes specific attention to four regions of the foot and ankle:

- Posterior ankle

- Sustentaculum tali

- Plantar midfoot

- The level of the sesamoids

The ankle and hallux are held in either a neutral or dorsiflexed position to place the FHL under tension. Proximally, the muscle belly and the musculotendinous region are palpated just posterior and lateral to the posterior tibial tendon. Medially and inferior to the sustentaculum tali, the FHL can be palpated as it courses through the fibro-osseous tunnel. At the plantar surface, the FHL can be palpated just plantar to the navicular and medial cuneiform, and it can be palpated as it traverses the knot of Henry. Distally, the FHL is palpated as it travels between the sesamoids(7).

Typical objective findings include:

- Tenderness to direct palpation.

- Reduced first MTP motion and/or Interphalangeal motion.

- Pseudo-hallux rigidus. Limited dorsiflexion in the presence of FHL tenosynovitis without first MTP degenerative changes has been coined ‘pseudo hallux rigidus’. Pseudo hallux rigidus is thought to result from nodular tenosynovitis proximal to the fibro-osseous tunnel, which limits the excursion of the FHL and thus limits first MTP joint dorsiflexion(7). Stenosing tenosynovitis of the FHL at the level of the sesamoids can present as inability to actively flex the hallux at the IP joint(18).

- Positive FHL stretch test. This test evaluates the influence of the FHL on first MTP motion; a positive finding is suggestive of ‘pseudo hallux rigidus’. This test is performed by assessing first MTP motion in both in maximal plantarflexion and moderate dorsiflexion of the ankle(7). To perform the test properly, the first metatarsal (MT) head should be stabilised to prevent compensatory first MT head plantar flexion. A positive test consists of discomfort at the first MTP or a decrease in first MTP joint motion by 20 degrees with ankle dorsiflexion. To assess the effect of the FHL on IP joint motion, place the ankle in a neutral position and stabilise the first MTP joint; limited motion at the IP joint is suggestive of FHL tenosynovitis at the level of the sesamoids(15, 18).

- Symptoms may be further provoked with inversion and eversion of the ankle(19). With ankle inversion, the size of the tarsal tunnel may decrease, causing further compression or irritation to the FHL tendon. Conversely, during eversion of the ankle, tension results causing increased pressure to be placed upon the structures within the tunnel, which leads to further aggravation of the symptoms. With careful palpation accompanying resisted plantarflexion of the great toe, the true site of irritation can be detected, and if the patient is questioned carefully, the examiner will find that the pain is deeper than that of Achilles tendinitis.

Imaging

Diagnostic ultrasound and MRI still provide the most valuable and accurate picture of damage and trauma in and around the FHL tendon.Treatment

In addition to direct stretching and strength work for an injured FHL muscle and/or tendon (discussed below), the therapist can also assess and manage issues throughout the entire kinetic chain, which may impact on the amount of movement and stress the foot and ankle sustains during normal functional sports specific movements. For example, a dancer with restricted hip external rotation may compensate with more foot turn out and eversion, which may lead to an overload injury to the FHL.Direct muscle strengthening for an injured FHL muscle and tendon may include the following type of exercises. These are listed as progressions with the first exercises being non-weight-bearing exercises, and the later examples being suitable alternatives when the athlete can fully weight-bear. All these exercises are designed to be performed in subtalar joint neutral positions so the athlete will need to be cued and coached on how to hold a neutral position.

Resisted plantarflexion of the big toe (theratubing)

Using a length of theraband or theratubing, place the tube/band around the big toe (pictured left) and actively plantar flex both the big toe and foot (pictured right).

Marble pickups

Using the 1stand 2ndtoes pick up a marble in dorsiflexion (pictured left) and drop it into a cup using plantar flexion.

Seated towel scrunch with a heel lift off (seated)

In sitting, place a towel under the foot on a slippery floor such as tiled or wooden floor. Actively scrunch the big toe and then actively lift the heel off the floor. Note the neutral dorsiflexion/plantarflexion posture in the start position (pictured left) and the big toe plantar flexion with ankle plantar flexion in the finish position (pictured right).

Towel scrunch with a heel lift off (standing)

Exercise as above but in standing. Note the neutral pronation/supination posture in the start position (pictured left) and the big toe flexion and ankle plantar flexion at the finish (pictured right).

Edge hovers

Standing on the edge of a step with the 1stand 2ndtoes supported with the three outside toes hovering in space (as pictured left), actively press the 1sttoe into the step and attempt to lift and hold the heel off the step (as pictured right). These can be held for 15-20 second holds.

Stretching of the FHL may at times be necessary, especially in the presence of a hypertonic and tight FHL muscle belly. However, in many cases the cause of the FHL injury is in fact over-stretching in and around the fibro-osseous tunnels - therefore stretching the muscle and tendon may in fact be counterproductive. Conversely, the FHL may become tight and constricted following an ankle plantarflexion/inversion injury, which compresses the tendon aggressively. The same is true following a syndesmosis injury, whereby the FHL tendon may be subjected to high tensile and torsional loads due to the talus rotating on the mortise. If the FHL does need to be stretched, the example below is an effective way to stretch the muscle safely.

FHL Stretch.

Place a rolled up towel or thin yoga mat between the wall and floor. Place the big toe into a dorsiflexed position and bring the knee towards the wall. Hold 20-30 seconds.

Conclusion

The FHL muscle and tendon are important structures that flex the big toe and help maintain rear foot and mid foot stability. In locomotion the FHL acts isometrically to maintain tension and arch support throughout mid stance to toe off during walking and running. It is a muscle-tendon unit that may be readily injured in a ballet population and sports that require aggressive plantarflexion of the ankle with the big toe in dorsiflexion.References

- Bone Joint Surg. 78A:1491-1500, 1996

- Am J Sports Med. 1977;5:84-88

- J Orthop Sports Phys 1983; 5: 204-206

- Norris R. Common Foot and Ankle Injuries in Dancers. In: Solomon R, Solomon J, Minton S, eds. Preventing Dance Injuries. 2nd ed. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics; 2005: 39-51

- Travel and Simons.Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. The Lower Extremities (Volume 2). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia.

- J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78-A: 1386-1390

- Foot Ankle Int. 2005; 26: 291-303

- Brunnstrom, SM: Clinical Kinesiology. Philadelphia: FA Davis CO, 1972

- J Dance Med Science. 2000; 4:86-89

- Sports Med. 1995; 19(5):341-57

- J Biomech.2008;41(9):1919-28

- Foot Ankle Int. 19:356-362, 1998

- J Pediatr Orthop. 1982; 2: 582-586

- Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 2005; 20: 99-102

- Foot Ankle Int. Aug;24(8):591-6, 2003

- Foot Ankle Int. Jan;23(1):51-5, 2002

- BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders; 8: 1 10-15. 2007

- Foot Ankle. 2:46-48, 1981

- Foot Ankle Int. 1999; 20:721-726

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Injury Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.