You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Unusual Injuries: Quadrilateral Space Syndrome

Athletes with persistent and undiagnosed shoulder pain may suffer from the rare but painful quadrilateral space syndrome. Chris Mallac unravels this complex diagnosis and offers practical treatment solutions.

Quadrilateral Space Syndrome (QSS), first described in 1983, is a rare and unusual shoulder pathology primarily seen in male volleyballers, swimmers, and baseball pitchers(1,2). Athletes with QSS are usually 20-40 years of age and repeatedly move their dominant arm into extreme abduction with external rotation ranges because of their sport. This syndrome is difficult to diagnose because it often imitates other shoulder pathologies.

Relevant Anatomy

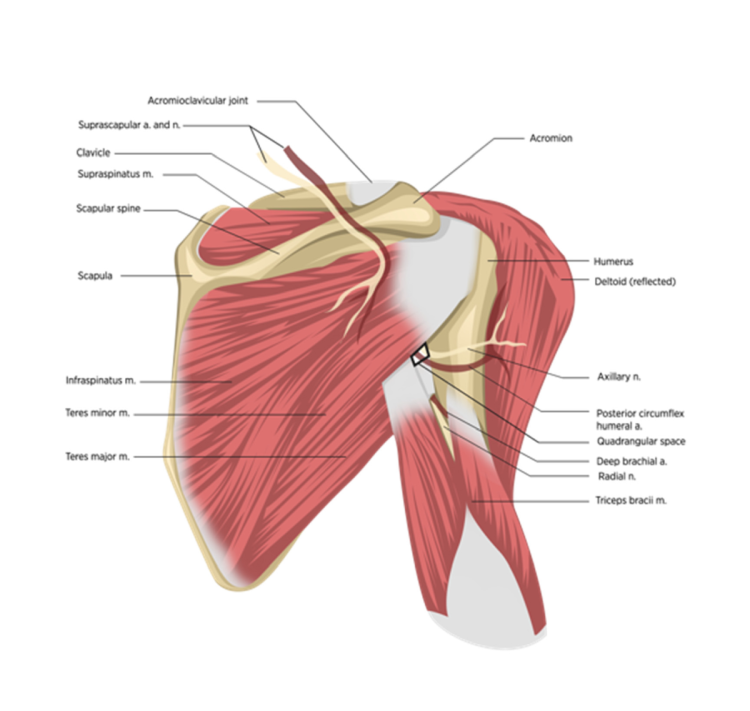

The following anatomical boundaries in the posterior shoulder (see figure 1) define the quadrilateral space (QS)(3):

- Superiorly – Teres minor

- Inferiorly – Teres major

- Medially – Long head of the triceps

- Laterally – Surgical neck of the humerus

Within the space formed by these anatomical boundaries lies the axillary nerve (which innervates the deltoid and the teres minor) and the posterior humeral circumflex artery (PHCA). The axillary nerve is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It travels anterior to the subscapularis to then pass under the axillary recess of the shoulder joint as it enters the QS to branch into the anterior (anterior and middle fibers of the deltoid) and posterior (posterior deltoid and teres minor) branches(4). A sensory branch travels with the posterior trunk and supplies the regimental badge area over the lateral aspect of the upper arm.

Pathogenesis

Any mechanical or pathological compression of the QS can lead to compression of the contents that pass through it. Neurogenic QSS occurs when the compression primarily affects the axillary nerve. A compression that mostly involves the PHCA, is called a vascular QSS. Compression of both the nerve and the artery is called a mixed QSS(2).

“Any mechanical or pathological compression of the QS can lead to compression of the contents that pass through it.”

There are several possible causes of neurogenic QSS. These include(2,5):

- Fibrous bands that develop within the QS compress the area with shoulder abduction and external or internal rotation(6,7). These fascial bands, which originate from the thick fascia overlying the long head of triceps and attach to the teres major, tighten during abduction and rotation movements(6).

- Direct trauma that impinges the axillary nerve.

- Hypertrophy of a muscle that borders the QS.

- A labral cyst.

- Sinister pathologies such as osteochondroma, lipoma, or axillary schwannomas(8).

A cadaver study found that the long head of the triceps has a thick fascial layer in the proximal part of the muscle-tendon as it approaches the infra-glenoid tubercle(6). It forms a distinct fibrous sling across to the teres major muscle. The sling became tight when the arm was abducted 90º and moved into internal and external rotation. The most compression occurred during the movement into internal rotation as the shoulder twists. Athletes demonstrate this motion during follow-through after throwing a ball and the pulling portion of the freestyle swim stroke(6).

The vascular form of QSS is usually caused by repetitive trauma to the PCHA wall during external rotation in abduction movements. The PHCA winds around the neck of the humerus and may be subject to repetitive tensile forces leading to possible thrombosis and degenerative aneurysm(2). This pulley mechanism around the neck of the humerus may then lead to blood flow turbulence in the bend of the PHCA. The blood vessel damage may then progress to aneurysmal degeneration and thrombosis(2).

The reported incidence of QSS is very low. One study reported that only 0.8% of patients showed evidence of QSS on MRI imaging(3). However, in this study, patients underwent MRI scans looking for other pathologies not suspected to be QSS. The MRI finding of teres minor atrophy was found incidentally in these patients.

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of QSS are often vague, poorly defined, and imitate other pathologies. The typical presentation of QSS is(2,5):

- A younger athlete (<40 years of age) involved in an overhead activity such as swimming, CrossFit, volleyball, or baseball.

- Pain is insidious in onset, initially minor and intermittent, hard to localize exactly, and becomes more severe and constant over time.

- Holding the shoulder in flexion, abduction, and external rotation may exacerbate symptoms(9,10).

- Neurogenic signs and symptoms include:

-

- Paresthesia – non-dermatomal to the forearm

- Weakness

- Fasciculations

- Muscle atrophy

- Tenderness in the QS.

- Vascular signs and symptoms include:

-

- Coolness, pallor or cyanosis of the hand.

- In extreme cases, aneurysm or thrombosis of the PHCA can lead to distal embolism causing ischemia of the fingers, loss of pulses, cold intolerance, and splinter hemorrhage due to the vascular back up into the axillary artery(2).

QSS is often a missed pathology as the symptoms may be similar to and co-exist with other shoulder pathologies. A list of possible differential diagnosis includes(3,11):

- Rotator cuff injuries, particularly infraspinatus lesions.

- Referred pain syndromes from the cervical spine.

- Cervical spine pathologies such as C4/5 disc bulge or facet joint irritation.

- Posterior labral injuries.

- Thoracic outlet syndrome.

- Brachial neuritis.

- Joint osteoarthritis.

- Suprascapular nerve injuries.

- Damage to the axillary nerve from a humeral head fracture, shoulder dislocation, or blunt trauma(5).

Related Files

Diagnostic Imaging

Xray

Plain films are used to exclude fracture and bone masses. These are otherwise unremarkable and not useful in diagnosing QSS(2).

Electromyogram (EMG)

An EMG may reveal denervation of the teres minor or deltoid with decreased amplitudes along the axillary nerve(2,12). An EMG can also help rule out other neurologic causes of pain, such as the cervical spine or brachial plexus pathology.

“In confirmed cases of QSS, the first line of management is activity modification and physical therapy modalities.”

MRI

An MRI is usually the first choice in imaging. An MRI may show fatty atrophy of the teres minor, suggesting denervation of the axillary nerve. This test also helps exclude other shoulder pathologies as causes of discomfort(13).

Arteriography

Arteriography was the original method used to identify QSS. A subclavian arteriogram detected the compression of the PHCA with the arm in abduction and external rotation. Most often, clinicians performed this test bilaterally to compare the blood flow of the injured arm to the unaffected side(11). However, some studies show that this approach may have low specificity. In one report, 80% of asymptomatic subjects showed PHCA occlusion(14). Due to its high rate of false positives, this method is no longer used in clinical practice.

Diagnostic Block

A lidocaine block with 5ml of 1% lidocaine in the QS two to three centimeters inferior to the posterior shoulder portal is another diagnostic tool. If the tenderness in the QS resolves after the injection, and there is no pain with an active throwing motion, then the test is positive for QSS(13).

Treatment

Conservative management

In confirmed cases of QSS, the first line of management is activity modification and physical therapy modalities. These may include:

- Friction massage

- Soft tissue massage

- Stretching of the teres muscles and long head of triceps.

- Thoracic mobility exercises.

- Lumbo-pelvic mobility and stability to ensure force generation through trunk rotation instead of pure shoulder internal rotation in throwing movements.

- Scapular stabilization exercises focusing on serratus anterior and lower trapezius may help place the scapula in a better position and reduce the compression of the axillary nerve by the surrounding muscles(11).

- While an ultrasound-guided injection of an anesthetic and corticosteroid may be used as a diagnostic block, this strategy may also help manage perineural inflammation(15).

Surgical management

Those patients who fail conservative management after six months or more may benefit from decompression surgery.

Surgeons dissect the axillary nerve to ensure it is competent. The arm is placed in abduction and external rotation to ensure that the axillary nerve glides freely, and there is a strong pulse in the PHCA(16). Other causes of structural compressions, such as fibrous bands, may also be excised.

Those patients who fail conservative management after six months or more may benefit from decompression surgery.

In the case of vascular QSS, surgeons ligate the pathological component of the PCHA to prevent further progression of an embolism. They also perform a thrombectomy on any distal emboli. A three to six month period of anticoagulant therapy may follow this approach(2).

Post-surgical rehabilitation involves early shoulder mobilization in the form of pendulum exercises. Athletes must avoid hyperextension, abduction, and external rotation for four weeks after surgery. In this early period, focus on thoracic spine mobility and scapular muscle strengthening. In particular, the teres minor and major may have suffered some denervation fatty atrophy and become weak. Also, start gentle range of motion into shoulder flexion and internal rotation. After four weeks, begin range of motion and strength work into abduction and external rotation.

Conclusion

Although an unlikely pathological entity in overhead athletes, QSS may lead to vague and poorly localized posterior shoulder aches and pains with non-dermatomal paresthesia over the lateral aspect of the shoulder and arm. It usually affects athletes involved in sports that require abduction and external rotation, such as throwing. An MRI is the best option to investigate this condition, and an axillary nerve block may be used to confirm the diagnosis. Manage QSS conservatively with activity modification, NSAID’s, soft tissue therapy to the contents of the QSS, and scapular stabilization exercises for a minimum of six months. Those who fail conservative management have good outcomes with surgical decompression.

References

1. J Hand Surgery. 1983. 8. 65-70. / 2. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 382–394 / 3. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005, 184, 989–992. / 4. Int J Sports Phys Therapy. 2015; 10. 347-353. / 5. Hangge J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 86 / 6. J Shoulder Elbow Surgery. 2008. 17(1). 162-164. / 7. J. Hand Surg. Asian Pac. 2017, 22, 125–127. / 8. HSSJ (2006) 2: 154–156 / 9. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2007, 15, 249-256. / 10. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2007, 15, 281–289. / 11. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, e9 / 12. Am J Phys Med and Rehabilitation. 2015; 94; e1-5. / 13. Case Rep Orthop. 2015; 2015: 378627. / 14. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1994, 163, 625–627 / 15. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018, 27, 650–956. / 16. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1991, 87, 911–916

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.