You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Sesamoid stress fracture: no small issue

Sesamoid bones are some of the smallest in the body. Yet, they can pose a big problem when injured. Trevor Langford discusses the anatomy, biomechanics, and clinical relevance of a stress fracture of the sesamoid bones and reviews management options.

Sports such as running, dancing, and gymnastics often require forceful forefoot dorsiflexion while in a weight-bearing position. This posture places excessive stress on the sesamoid bones of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ). Repetitive stresses in the area can result in stress fractures of the small bones, sometimes called hallux sesamoid fractures(1,2). These types of injuries make up one to three percent of all stress fractures(2).

Acute fractures occur due to a single maximal force, whereas a stress fracture results from repetitive submaximal loading, which leads to microfractures in the bone(3). The initial failure of bone without an overt fracture line is called a stress reaction. With persistent loading, the stress reaction can become a stress fracture(3).

Females generally have a higher incidence of stress fractures in the feet(3). The theory is with a wider pelvis and increased Q-angle, females are more prone to pronation of the foot and ankle and uneven loading(3). Females may also be more susceptible to stress injury if they are in relative energy deficiency (RED-S), a syndrome that affects males too. Osteopenia and osteoporosis can occur in athletes with RED-S, making them more susceptible to stress injuries, despite repetitive bone loading(4).

Anatomy and biomechanics

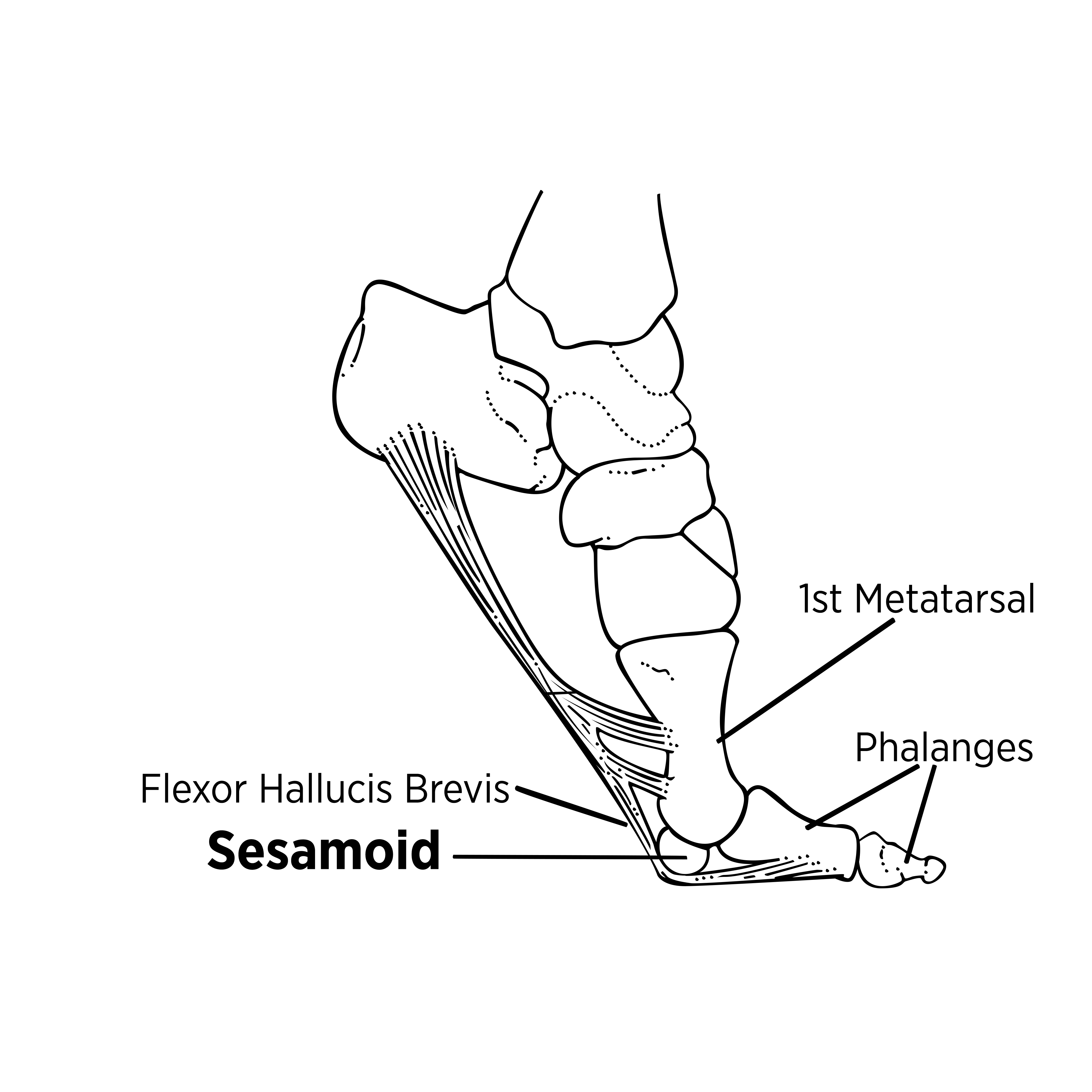

The medial and lateral sesamoid bones (also referred to as the tibial and fibular sesamoid bones, respectively) of the first MTPJ are located on the plantar surface of the distal first metatarsal (see figure 1). They vary in their size and are typically oval or round(5). The sesamoid bones lie encased within the flexor hallucis brevis tendon which attaches to the first proximal phalanx of the first toe(6). The articular surfaces of the medial and lateral sesamoid bones glide along the sesamoidal grooves, which are divided by a central plantar ridge known as the central crista(1). Stress fractures of the medial sesamoid bone are more common due to its location. This medial area experiences greater forces during toe-off than the lateral side, especially in patients with a hallux valgus deformity(3).

Figure 1: Functional anatomy of the sesamoid bones of the foot

The sesamoid bones of the foot perform three primary functions(6):

- Act as a fulcrum and enhance the mechanical leverage of the first toe flexors;

- Help absorb some of the load-bearing forces at the first toe;

- Elevate the first metatarsal so it can plantarflex while the phalanges dorsiflex (see figure 1).

During the gait cycle, the first ray transfers forces of up to 60% of a person’s weight to the first MTPJ(1). Even though the sesamoid bones are about the size of a pea, they bear the lion’s share of this load transfer.

Examination and assessment

A variety of intrinsic and extrinsic factors may contribute to stress fractures of the foot and ankle (see table 1). Injured athletes usually describe a recent increase in training distance, intensity, or duration, along with reduced recovery times or changes in playing surfaces(3). They complain of a gradual onset of pain on the plantar aspect of the first MTPJ during toe-off when running or jumping(2). Passively moving the first toe into dorsiflexion increases the pain.

Obtain a detailed history of diet, medications, menstrual cycle, footwear history, and training programs(3). Differential diagnoses for plantar pain around the MTPJ are sesamoiditis, chondromalacia, first MTPJ joint capsular tear (turf toe), flexor hallucis tendonitis, and arthritis(2,7).

| Intrinsic Risk Factors | Extrinsic Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Cavus feet | Type of activity (i.e. running/jumping) |

| Leg length discrepancies | Excessive new training program |

| Excessive forefoot varus | Inappropriate footwear or equipment |

| Tarsal coalitions | Poorly executed technique |

| Tight heel tendons | Type of training surface |

| Osteopenia/osteoporosis | Sleep deprivation |

| Poor vascular supply | |

| Abnormal hormonal levels |

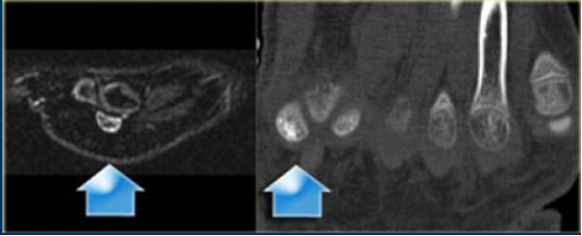

An X-ray may not detect a stress fracture until resorption, sclerosis, or callus formation occurs(3). Therefore, magnetic resonance imaging, isotopic bone scans, or computed tomography (CT) are more sensitive in the initial period after the onset of symptoms (see figure 2)(1,2).

Figure 2: Computed tomography (CT) of a sesamoid fracture

A stress fracture of the medial (tibial) sesamoid bone confirmed by high signal intensity of the medial sesamoid bone on the CT of a 14-year-old footballer with persistent plantar foot pain. *Image reprinted with permission.

Management options

Scottish researchers conducted a systematic review of 14 studies (168 cases). They found that the time between the onset of symptoms and diagnoses of sesamoid stress fracture was anywhere between 16 weeks and 15 months(2). Of the 168 cases, 22 received conservative management while 146 underwent surgery. The conservative approach included activity modification, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication, shoe modification, and custom J-shaped orthotics.

Both treatment approaches were fairly successful, with 86% of the conservatively managed and 95% of the surgically managed athletes returning to sport(2). However, the surgical candidates returned to sport after 11 weeks, while the conservatively managed group took 13.9 weeks to get back to the playing field(2). Furthermore, despite their return to play, nearly all who got conservative care continued to experience pain. Their persistent symptoms resulted in roughly one-third of them eventually choosing a surgical intervention, which further delayed their ultimate return to sport.

There were no complications reported following partial sesamoidectomy, and only one study in the review reported removing a screw after one year of internal fixation. Although complete sesamoidectomy surgery had a slightly quicker return to sport, there were some reported complications, including(2):

- A hallux valgus deformity (4%)

- A hallux varus deformity (4%)

- Post-operative scarring with neuroma symptoms (8%)

- Transient paresthesia (18%)

- Persistent pain (18%)

Conclusion

To prevent a stress fracture, monitor and modify the intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors associated with athletes and their sport. Always consider conservative treatment during the initial management of sesamoid stress fractures. The most effective is a course of immobilization and offloading in an air-cast boot for six weeks, followed by strengthening and gait modification. However, surgery may provide a quicker and more long-term return to sport. As noted in the Scottish review, delayed diagnosis may contribute to persistent pain after conservative measures(2). An earlier diagnosis could prevent surgery and result in better outcomes with conventional treatment.

References

- The Foot & Ankle Journal. 2008;1(9):3

- British Med Bulletin. 2017;122:135-149

- Sports Health. 2014 Nov;6(6): 481-491

- J Am Acad Orthop Surg.1998 Nov;6(6):349-357

- Insights Imaging. 2013; 4: 581-593

- Phys Ther. 1999 Sept;79(9): 854-859

- Sports Health. 2010 Nov.2(6):487-494

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.