You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Mind Your Head: 2023 Concussion Update

The Concussion in Sport Group has conducted its sixth International Conference. The conference builds upon previous meetings and involved systematic reviews by author groups over three and a half years. Jason Tee summarizes their findings and recommendations on concussions in sports, providing the most up-to-date information on what is currently considered best practice for preventing and managing athletes who

suffer concussions.

New Zealand v South Africa - World Cup warm-up - South Africa’s Kwagga Smith in action with New Zealand’s Anton Lienert-Brown Action Images via Reuters/Matthew Childs

In recent years, concussion has gained greater attention due to the impact on athlete health. Numerous accounts of retired athletes suffering from neurological conditions such as dementia, depression, anxiety, and other mental health challenges have populated the news media, creating a heightened awareness of the potential long-term concussion effects. The increased popular concern regarding sport-related concussion is illustrated by the success of the 2015 film Concussion, starring Will Smith, which earned over $50 Million worldwide. Typically, Hollywood doesn’t like to let the facts get in the way of a good story, and there are some noted inaccuracies in the Concussion film.

On the other hand, a committed group of international medical professionals and concussion experts known as the Concussion in Sport Group has been meeting for over 20 years to discuss and refine concussion detection, diagnosis, and treatment. They recently published their sixth consensus statement on concussion in sports. It represents the most up-to-date, evidence-informed understanding of concussion in sports and clarifies the current best practice management(1).

Updated sport-related concussion definition

A concussion is a multifaceted neurological condition that can manifest differently depending on individual characteristics and the mechanism and severity of the injury. As a result, two athletes with concussions may present with very different signs and symptoms. One of the clear challenges in managing concussions is that many are either misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all because of this variable presentation. The Concussion in Sport Group reached a majority agreement on the definition of sport-related concussion.

Updated Concussion Definition

Sport-related concussion is a traumatic brain injury caused by a direct blow to the head, neck, or body resulting in an impulsive force being transmitted to the brain that occurs in sports and exercise-related activities. This initiates a neurotransmitter and metabolic cascade, with possible axonal injury, blood flow change, and inflammation affecting the brain. Symptoms and signs may present immediately or evolve over minutes or hours and commonly resolve within days but may be prolonged. Sport-related concussion results in a range of clinical symptoms and signs that may or may not involve loss of consciousness*

*definition abridged from Br J Sports Med. 2023 Jun;57(11):695-711.

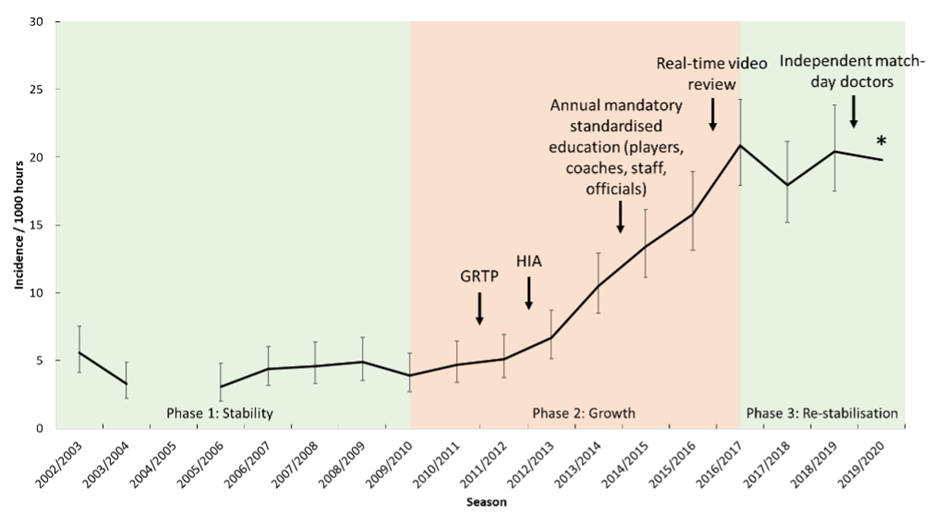

Sport-related concussion incidence

It is difficult to estimate the incidence of concussions in sports because of the inherent difficulties in diagnosing and reporting the condition. In 2013 the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine estimated that 3.8 million sports-related concussions occur in the USA each year, but half of these go unreported(2). Since this initial estimate, several research studies have indicated that concussion incidence is increasing year-on-year(3,4). The increase in concussion incidence in recent years may result from increased awareness and reporting. Ultimately, the higher concussion rates are a positive outcome because they reflect increased diagnosis and treatment(5).

One concussion is estimated for every 4348 athletic exposures for high school sports participants(4,6). This may not sound like a large number, but when we consider that in Western countries, approximately half of the youth population actively participates in sports, the total burden of concussion is huge. The frequency of concussions in youth sports participants is also of concern because of the effect on learning. Concussion incidence is higher in collegiate and professional sports leagues than youth sports(7). Contact and collision sports such as rugby, American football, and wrestling have higher concussion rates than non-contact sports(2). Furthermore, female sports participants are at greater risk of concussion (almost twice as high) than their male counterparts playing the same sports(4,6).

Recognizing concussion

The best practice for managing concussion is that any sports participant suspected of having a concussion should immediately be removed from play and should not return to play without being referred to a healthcare professional experienced in the treatment of concussion. A healthcare professional should only return an athlete to play if they can conclusively determine that the signs or symptoms identified were not due to concussion.

Return to learn and play

The management of return to play/learn for any participant that has suffered a concussion is guided by their symptoms. As participants progress through the return to play and return to learn protocols below, if any activity results in a more than mild exacerbation of symptoms, the participant should stop and attempt to complete the same step in the rehabilitation protocol the next day. Returning to play and learn protocols aim to return participants to their normal daily activities as soon as possible while minimizing the potential for further injury. Most concussed sports participants return to full school participation within ten days and full sports participation within one month(1).

Table 1: Return to sport protocol

| Step | Exercise Strategy | Exmaple activities |

| 1 | Symptom- limited activity. | Daily activities that do not exacerbate symptoms (e.g., walking). |

| 2 | Aerobic exercise: 2A—Light (up to approximately 55% maxHR), then 2B—Moderate (up to approximately 70% maxHR). | Stationary cycling or walking at a slow to medium pace. May start light resistance training that does not result in more than mild and brief exacerbation of concussion symptoms. |

| 3 |

Individual sport-specific exercise.

Note: Care should be taken to minimize the risk of accidental head impact.

|

Sport-specific training away from the team environment (e.g., running, change of direction, and individual training drills away from the team environment). No activities at risk of head impact. |

|

Steps 4–6 should begin after the resolution of any symptoms, abnormalities in cognitive function, and any other clinical findings related to the current concussion, including with and after physical exertion. Athletes experiencing concussion-related symptoms during Steps 4–6 should return to Step 3 to fully resolve symptoms with exertion before engaging in at-risk activities. A healthcare professional should provide a written determination of readiness to RTS before unrestricted RTS as directed by local laws or sporting regulations.

|

||

| 4 | Non-contact training drills. | Exercise to high intensity, including more challenging training drills (e.g., passing drills, multiplayer training), can integrate into a team environment. |

| 5 | Full contact practice. | Participate in normal training activities. |

| 6 | Return to sport. | Normal gameplay. |

Each step requires a minimum of 24 hours before progressing.

Table 2: Return to learn protocol

| Step | Mental activity | Example activities |

| 1 | Daily activities that do not result in more than a mild exacerbation of symptoms related to the current concussion. | Typical activities during the day (e.g., reading) while minimizing screen time. Start with 5–15 min at a time and increase gradually. |

| 2 | School activities. | Homework, reading, or other cognitive activities outside of the classroom. |

| 3 | Return to school part-time. | A gradual introduction to schoolwork. May need to start with a partial school day or greater access to rest breaks during the day. |

| 4 | Return to school full-time. | Gradually progress in school activities until a full day can be tolerated without more than mild symptom exacerbation. |

Each step requires a minimum of 24 hours before progressing.

A notable change in the treatment recommendations in the latest concussion consensus statement is the shift to introducing daily activities and aerobic exercise as soon as possible. Previous recommendations encouraged 24-48 hours of complete rest and isolation, and this has been updated to promote relative rest, which motivates a rapid return to activities of daily living. Similarly, absolute physical rest is now discouraged. Concussed sports participants are now encouraged to walk during the initial 24-48 hours following their concussion and to introduce light aerobic acivity as soon as possible (provided that it does not more than mildly exacerbate their symptoms).

Concussion prevention

The preferred strategy for managing concussions is trying to ensure that concussions do not occur in the first place, and there have been some significant strides in this area in recent years.

Policy and rule changes

Two of the most impactful concussion reduction strategies in recent years have resulted from governing body mandated changes in rules and practices within sports. Ice hockey has implemented a rule change that has prevented body checking at the child and adolescent levels of the game, which resulted in a 58% reduction in concussion incidence(8).

USA Football introduced several guidelines limiting the amount of contact practice that can take place in youth and high school football. Notably, these guidelines limit players to 30 minutes of full-contact training per session and 60 minutes of full-contact training per week, resulting in a 64% reduction in practice-related concussions(8).

Protective equipment

In ice hockey, using mouthguards reduces the incidence of concussions by 28%(8). Limited information is available from other sports in the area of mouthguard impact. Still, it would seem that using a mouth guard for any collision sport is prudent, and this adjustment has limited downside.

Neuromuscular training

In rugby, there is evidence that regular participation in neuromuscular training reduces all injuries and, specifically, the incidence of concussion(9). While we await research from other sports, there seems to be little downside to being physically well-conditioned.

Conclusion

The current research agenda calls for clinicians and researchers to develop more conclusive evidence regarding the potential long-term effects of repeated concussions. The evidence available is somewhat contradictory and generally based on association rather than cause and effect. There is a need for higher-quality research that can clearly quantify the risks of repeated concussions for professional athletes. In addition to the need for a better understanding of the long-term effects of concussion, some groups are underrepresented in concussion research, most notably disability athletes and child (<12 years old) sports participants. As the evidence builds, clinicians will be able to better support athletes suffering from concussions. The latest update provides proactive treatment recommendations and more clarity on the treatment pathways for athletes and clinicians.

References

- Br J Sports Med. 2023 Jun;57(11):695-711.

- Br J Sports Med. 2013 Jan ;47(1):15-26.

- Br J Sports Med. 2019 Aug;53(15):969-973

- Am J Sports Med. 2011 May;39(5):958-63.

- blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2021/11/17/concussion-in-professional-mens-rugby-union-improvement-in-detection-or-increased-risk/

- Br J Sports Med. 2016 Mar;50(5):292-7.

- J Athl Train. 2017 Mar;52(3):167-174

- Br J Sports Med. 2023 Jun;57(12):749-761.

- Br J Sports Med. 2017 Aug;51(15):1140-1146

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.