You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Masterclass on Ankle injury: Part I - when instability becomes chronic

In the first of this three-part masterclass article, Chris Mallac discusses the progression from acute ankle sprain to chronic and recurrent instability, the relevant anatomy and biomechanics, and how chronic instability can be identified in the athlete.

Ankle sprains are one of the most common injuries experienced by athletes, and account for a large percentage of lost time from competition(1,2). The frequency of acute ankle sprain is relatively high in the athletic population, with some researchers claiming that injuries to the ankle joint account for 20% of all joint injuries(3). A comprehensive review found that lateral ankle sprain was the most common ankle injury in 33 out of 43 sports(1). The lateral ligament complex is the most frequently injured ankle structure, with medial ligament (deltoid) injuries and syndesmosis injuries being less prevalent.

The majority of acute ankle injuries recover reasonably quickly with conservative treatment, which incorporates strengthening, ankle mobilisations, balance and proprioception and protective braces and strapping. However, a number of acute ankle sprain sufferers may go on to develop later-stage chronic or recurrent ankle instability. This results in a feeling that the ankle feels vulnerable, episodes of catching and ongoing pain and further episodes of repeat ankle sprains(4). One of the highest risk factors for an ankle injury is in fact a history of previous ankle injury(5). Of further significance is that ankle sprains have a high rate of recurrence (as high as 80% in high-risk sports)(5,6). This suggests that many ankle sprain sufferers will most likely sprain their ankles again, and this may then cascade to late stage chronic ankle instability (CAI).

Relevant anatomy and biomechanics

When the ankle is fully loaded into weight-bearing and dorsiflexion, the articular surfaces and joint congruency are the main stabilisers of the ankle, and prevent the talus from rotating and sliding(7). The ligaments of the ankle do play a role in stability in this position; however they become a lot more crucial in ankle stability as the ankle approaches plantarflexion. In plantarflexion, the talocrural joint is in a loose-packed position and therefore joint congruency and inherent joint stability are reduced. This means the ankle ligaments play a much larger role in ankle stability (and thus are more vulnerable to injury) in this position.

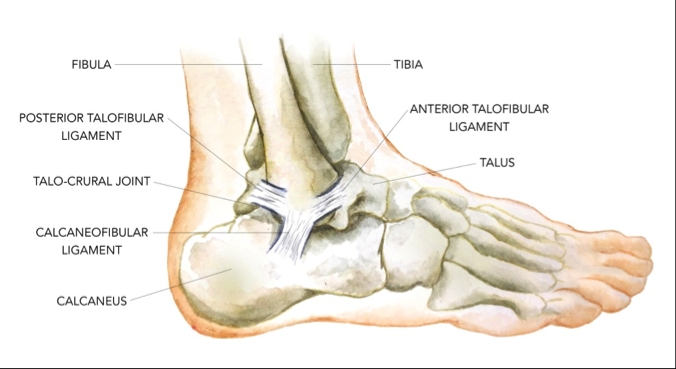

The ligaments of the ankle include the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), and deltoid ligament on the medial side of the ankle (see figure 1). The ATFL, PTFL, and CFL support the lateral aspect of the ankle, while the deltoid ligament provides medial joint stability. For the purposes of this article the deltoid ligament will not be discussed and the focus will remain on the lateral ankle ligaments, the ATFL, CFL and PTFL.

Figure 1: Lateral ankle ligaments

The ATFL courses from the lateral malleolus anteriorly and medially toward the talus at an angle of approximately 45 degreesfrom the frontal plane(8). The ATFL is an average of 7.2 mm wide and 24.8 mm long. Studies have shown that the ATFL prevents anterior displacement of the talus from the mortise, and excessive inversion and internal rotation of the talus on the tibia(7,9). The strain in the ATFL increases as the ankle moves from dorsiflexion into plantar flexion. Furthermore, compared with the PTFL, CFL, anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, and deltoid ligament, the ATFL demonstrates lower maximal load and energy to failure values under tensile stress. This is the reason why it is the most commonly injured ligament in the classic inversion with or without plantarflexion mechanism.

The CFL courses from the lateral malleolus posteriorly and inferiorly to the lateral aspect of the calcaneus at a mean angle of 133 degrees from the long axis of the fibula(8). The CFL restricts excessive supination of both the talocrural and subtalar joints. Studies have demonstrated that the CFL restricts excessive inversion and internal rotation of the rearfoot, and is most taut when the ankle is dorsiflexed(7). Considering that the CFL is under less strain in plantarflexion, injury to this ligament is not as common. It is more commonly injured if the inversion mechanism occurs in neutral to dorsiflexion positions - hence the CFL runs a distant second as the most-often injured of the lateral ankle ligaments.

The PTFL runs from the lateral malleolus posteriorly to the posterolateral aspect of the talus. The PTFL has broad insertions on both the talus and fibula and provides restraint to both inversion and internal rotation of the loaded talocrural joint(7,8). It is the least commonly sprained of the lateral ankle ligaments as it is only under a strain load when the ankle is in full dorsiflexion; the congruency position where the talus and ankle mortise are closely locked together and hence relatively stable.

Other ligaments such as the syndesmosis ligament, subtalar joint ligaments, bifurcate ligaments and also the supporting tendons may also be injured in the inversion ankle sprains however they will not be discussed in the context of chronic ankle instability.

What is CAI?

The term chronic ankle instability (CAI) has been interchanged with other names and definitions in the literature such as ‘recurrent ankle instability’ and ‘residual ankle instability’. For the purposes of this article, the term CAI will be used. It has often been assumed that all cases of CAI follow the same sequalae from the original lateral ligament injury, which then progresses to episodes of recurrent giving way and CAI. This leads to the assumption that a consistent relationship between impairments and activity limitations exists. However, it is clear that sufferers of CAI are not a homogenous group but can consist of heterogenous groups of patients all with varying deficiencies and what leads to CAI may be multifactorial(10).

It has been reported that 32-74% of individuals with a previous history of ankle sprain suffer from some type of residual and chronic symptoms, recurrent ankle sprains, and/or perceived instability(11,12). Historically, CAI has been divided into two subgroups; mechanical and functional instability. Mechanical instability relates to the anatomical changes that follow an acute ankle sprain(13, 14). These include factors such as:

- Pathological laxity in the lateral ankle ligaments

- Altered joint mechanics of the talocrural joint and distal tibiofibular joint

- Synovial inflammation

- Soft tissue of bony impingement

- Degenerative changes

Functional instability is an ambiguous term that defines instability based on functional performance tests such as balance and proprioception, and a patient’s perception that the ankle feels ‘weak’ and ‘unstable’(14-17). This definition attempts to highlight and categorise the proprioceptive changes that follow lateral ligament injury. However, confusion and disagreement exists in the literature as to how mechanical and functional instability relate to each other - and if indeed they do interact(10).

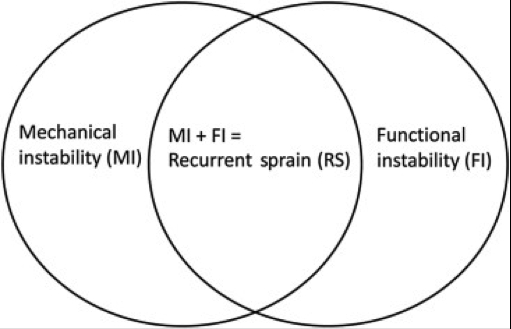

Hertel (2002) proposed arguably the best model, which describes CAI as ‘having components of mechanical and functional instability that are not mutually exclusive and co-exist on a continuum, and when combined lead to recurrent sprain’(13). The changes with mechanical instability (anatomical) are proposed to lead to insufficiencies that predispose the person to further episodes of instability. Functional instability results from impairments such as impaired proprioceptive and neuromuscular control. When mechanical and functional insufficiencies are both present, recurrent sprain results and Hertel defined ‘recurrent sprain’ as his third subgroup (see figure 2).

Figure 2: the three subgroups of the Hertel model(13)

Anecdotally however, participants have reported residual feelings of instability and ankle laxity after ankle sprain but have not reinjured their ankles. Furthermore, studies on patients with both mechanical and functional instability performed differently to patients with only functional instability in areas such as postural sway(18)and peroneal reaction times(19). This suggests that the Hertel model may not be completely inclusive of all types of CAI.

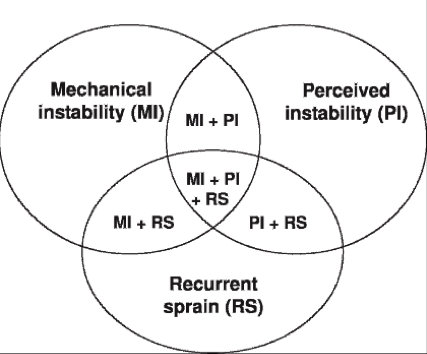

These inconsistencies led to an evolution of the Hertel model, which separates recurrent sprain from the presence of both instabilities. Hiller et al (2011) proposed to refine this model and expand the number of subgroups from 3 to 7 (see figure 3)(10). They also redefined functional instability as ‘perceived instability’ because the key feature of this subgroup was the patient’s perception that their ankle felt unstable, even in the presence of normal testing with functional tests. They retained the subgroups called ‘recurrent sprain’ and ‘mechanical instability’ and argued that these three subgroups may exist independently or in combinations. For example, it is possible to have ‘mechanical instability’ and ‘perceived instability’ but to not have ‘recurrent sprains’.

Figure 3: The seven subgroups of Hiller model(10)

The typical signs, symptoms and behaviours associated with CAI include(10):

- Giving way

- Mechanical instability (laxity on testing)

- Pain and swelling

- Loss of strength

- Recurrent sprains

- Functional instability (poor performance on balance and proprioception tests)

- Fear of uneven grounds

- Decreasing level of exercise and withdrawing from sport

Identifying CAI in patients

Identifying patients who may in fact be suffering CAI may appear on first inspection to be relatively simple. However there are significant differences in how researchers classify CAI exist. In the simplest sense, mechanical instability (anatomical) is identifiable on physical examination (anterior draw tests and talar tilt) and stress radiographs. Functional instability however reflects subjective, patient-reported complaints of the ankle instability with or without clinical laxity(20,21). For the clinician therefore, it can often be difficult to identify patients who do indeed have accepted CAI. They may appear to be unstable on physical testing such as laxity on the anterior draw and talar tilt but they may perform well on functional assessment. They may complain of no sensations of feeling vulnerable.

The International Ankle Consortium (a large focus group) attempted to categorise particular features of ankle injury that would lead to a consensus on how to actually define CAI, and to provide a selection criteria for patients with CAI(22). The primary purpose of this consortium was to categorise the selection criteria to define CAI for future research,; however the clinician may extrapolate these criteria to help the identify patients in clinic who may be suffering CAI.

Table 1 (developed by The International Ankle Consortium) shows the minimum standard inclusion criteria for enrolling patients that fall within the heterogeneous condition of CAI. Although the purposes of this criteria list was to select patients with CAI into future research studies, therapists may use this framework as a basis for deciding whether or not their patient does indeed suffer from CAI.

| A history of at least 1 significant ankle sprain1. The initial sprain must have occurred at least twelve months prior to study enrolment2. Was associated with inflammatory symptoms (pain, swelling, etc)3. Created at least 1 interrupted day of desired physical activity4. The most recent injury must have occurred more than three months prior to study enrolment.We endorse the definition of an ankle sprain as ˜˜An acute traumatic injury to the lateral ligament complex of the ankle joint as a result of excessive inversion of the rear foot or a combined plantar flexion and adduction of the foot. This usually results in some initial deficits of function and disability. |

| A history of the previously injured ankle joint ˜˜giving way and/or recurrent sprain and/or feelings of instability.We endorse the definition of ˜giving way as ˜The regular occurrence of uncontrolled and unpredictable episodes of excessive inversion of the rear foot (usually experienced during initial contact during walking or running), which do not result in an acute lateral ankle sprain. |

| Specifically, participants should report at least two episodes of giving way in the six months prior to study enrollment.We endorse the definition of ˜˜recurrent sprain as two or more sprains to the same ankle.We endorse the definition of ˜˜feeling of ankle joint instability as ˜˜The situation whereby during activities of daily living (ADL) and sporting activities the participant feels that the ankle joint is unstable and is usually associated with the fear of sustaining an acute ligament sprain. |

| Specifically, self-reported ankle instability should be confirmed with a validated ankle instability specific questionnaire using the associated cut-off score. Currently recommended questionnaires:a. Ankle instability instrument (AII): answer ˜˜yes to at least five yes/no questions (this should include question 1, plus 4 others.)b. Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool (CAIT)c. Identification of Functional Ankle Instability (IdFAI) |

| A general self-reported foot and ankle function questionnaire is recommended to describe the level of disability of the cohort, but should only be an inclusion criterion if the level of self-reported function is important to the research question. Currently endorsed questionnaires:a. Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM)42: ADL scale , 90%, Sport scale , 80%b. Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS)43: , 75% in three or more categories |

Signs and symptoms of CAI

It has been mentioned above that conflict exists as to the exact nature and definition of what is CAI. For the treating clinician, decisions must be made - for example conservative management or referral to an orthopaedic specialist for an opinion on surgical options. So what are the classic signs and symptoms that may alert a clinician that this CAI may require surgical intervention? The summary points below may act as a guide but are by no means exhaustive. Many of these points have been adapted based on findings referred to above(10,13,22):

- Definite episode of previous lateral ankle sprain that led to pain, swelling, functional limitations and the need to avoid training and/or competition.

- The timeframes suggested from initial acute injury to present CAI may be one year from initial injury; if the sprains have been recurrent, then the previous one in the previous 3 months.

- A current awareness that the ankle still gives way and feels vulnerable, and this has occurred at least twice in the last six months.

- Poor scores on a selected range of functional questionnaires.

On examination, the following signs may or may not be present and these will highlight both the mechanical and functional contributions if they exist:

- Increased anterior draw test

- Possible increase in talar tilt

- Reduced ankle dorsiflexion as measured with a knee to wall test

- More than 4cms difference on the forward reach with the Star Excursion Balance Test

Imaging findings such as stress radiographs, ATFL attenuation on MRI and other soft tissue abnormalities may also indicate to the clinician that a degree of mechanical instability is present.

Conclusion

Ankle sprains continue to be an area of interest in sports medicine. Although research has produced advancements in prevention, diagnosis, and management, recent epidemiology studies have revealed that lateral ankle sprains remain a dominant sports injury. The majority of acute ankle sprains are managed conservatively, and on balance, the majority do have good functional outcomes. However, a small percentage of these ankle sprains may result in CAI, and these are the injuries that may require surgical intervention. The patho-anatomical reasons for CAI are multifactorial, relating to both anatomical deficits that lead to mechanical instability, and neuromuscular changes that lead to functional instability (or perceived instability). As a result recurrent sprains may be present. In the next edition of the Sports Injury Bulletin, part two will focus on possible surgical options to manage CAI and what is involved in the lengthy rehabilitation process.

References

- Sports Med. 2007;37(1):73–94

- Am J Sports Med. 1977;5:241–242.

- United States Bone and Joint Initiative. The Bone and Joint Decade: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States. http:// www.boneandjointburden.org/. Accessed November 1, 2013

- Am J Med. 2008;121(4): 324–331, e6

- Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:103–108

- J Athl Train. 2002;37(4):376–380

- Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:295–300.

- Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:72–77.

- Foot Ankle. 1988;9:59– 63

- Journal of Athletic Training 2011;46(2):133–141

- J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(2):163–169.

- Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(3):e14

- J Athl Train. 2002;37(4):364–375.

- J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47:678– 685

- J Athl Train. 2002;37(4):512–515.

- J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 1990; 11(12):605–611.

- J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66(2):209–212.

- Int J Sports Med. 1985;6(3):180–182.

- Foot Ankle Surg. 2000;6(1):31–38

- Foot Ankle Int 2006; 27: 854-866

- J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2008; 16: 608-615

- Gribble et al (2014) Selection Criteria for Patients With Chronic Ankle Instability in Controlled Research: A Position Statement of the International Ankle Consortium. Journal of Athletic Training 2014;49(1):121–127.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.