You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Masterclass: LARS - Part II. Rehabilitation following LARS procedure.

Returning an athlete following a ‘LARS reconstructed knee’ back to competitive status requires much more than simply restoring muscle strength and range of movement. An integrated approach encompassing full kinetic chain function enhancement is required. Additionally, an in-depth knowledge of strength and conditioning principles and how these apply to the systematic rehabilitation process and the long-term reconditioning of a LARS reconstructed knee is essential. Furthermore, ensuring the athlete remains injury-free requires ongoing management and regular monitoring.

Key considerations

Return to competition following a LARS procedure differs significantly compared to a standard graft repaired knee (see Tracy Ward’s article for guidelines on returning to sport after traditional graft). Due to the unique nature of the LARS reconstruction, time frames are compressed and accelerated. Table 1 below compares the ‘expected’ time frames for return to competition for a LARS reconstructed knee versus a traditional ACL reconstruction. This topic has received a significant amount of media attention in Australia, with some professional Australian Rules Football players returning as fast as 14 weeks post injury.| Physical Milestone | LARS reconstructed knee | Autograft reconstructed knee |

|---|---|---|

| Protected weightbearing | Usually unnecessary | Dependent upon concomitant meniscal repair so this may be 6 weeks |

| Return to running | 6 weeks post op | 12 weeks post op |

| Return to training | 9 weeks post op | 16-20 weeks post op |

| Return to competition | 14-16 weeks | 24-52 weeks |

The primary reason for the delayed return to competition in traditional ACL reconstructed knees with an autograft such as the hamstring or patella-bone-patella graft is the time it takes for the autograft to re-vascularise. Furthermore, the autograft has a harvested site that leads to donor site morbidity. Therefore the graft and the harvest site have to be protected until both have sufficient strength to be loaded. Conversely a LARS reconstructed knee is immediately protected by the nature of the artificial ligament matrix. The remaining ACL stump regrows through the matrix; however the knee is essentially stable during this process.

Stages of rehabilitation

When planning and delivering the stages of rehabilitation programmes , an understanding of the influence of load exposure, load attenuation and force generation is critical to provide clinicians with a clear understanding of the milestones that need to be achieved – and the rate at which they can pursued. The best way to approach the process, therefore, is to stage the approach to high performance and load resilience using a ‘phased’ or ‘milestone-based’ strategy, with each stage feeding into the next. In keeping with the exit-criteria approach, we do not move between stages according to the passage of time, but the accomplishment of functional goals.The four primary stages of knee rehabilitation following LARS reconstruction are:

- Protection and healing

- Restoring muscle strength and range of movement

- Integrated functional adaptation

- Sports-specific retraining

The time frame in each stage will depend primarily on the pathology we are dealing with. A simple LARS reconstruction will progress faster than a LARS that has associated meniscal repair, or if the femoral condyles and/or tibial plateau have residual bone oedema. The key objectives for each are discussed in more detail below.

Phase 1 – protection and healing

A critical early intervention following a LARS reconstruction is to protect the joint from further damage and to allow a supportive environment in which healing can take place. Dependent on the injury, this may require bracing, taping or even use of crutches. As soon as possible however, we want to restore normal gait mechanics as this has positive effects on proprioception and muscle activation. An effective way of graduating this is through an altered weight-bearing environment such as a pool.

The importance of removing effusions

Due to the nature of the arthroscopic surgery to repair a torn ACL with a LARS prosthetic, it is common for the patient to demonstrate a knee effusion post operatively. A knee joint effusion is an excessive amount of fluid within the synovial capsule of the knee indicating that the knee is inflamed or irritated (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Knee joint effusion

The exact patho-physiological mechanisms for an effusion and the necessary medical interventions are genuine concerns for the rehabilitation practitioner. Even small volumes of fluid (20-30mls) can result in a 50-60% reduction in maximal voluntary muscular activationThe Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 1988. 70-B(4): p. 635 – 638. Journal of Athletic Training, 2010. 45(1): p. 87-97. 3 Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology, 1988. 73: p. 305-314. Clinical Physiology. 1990. 10(5): p. 489-500., a process commonly referred to as ‘arthrogenic inhibition’Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 1993. 52: p. 829-834.. Moreover, small increases in intraarticular fluid (as modest as 5mls) increases the pressure within the knee joint. This can be a source of discomfort and concern for the athlete.

Furthermore, it has also been found that knee joint effusions will also alter the knee joint mechanics during landing tasksAmerican Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007. 35(8): p. 1269-1275.. Those individuals with a knee effusion tend to land with greater ground reaction forces and in greater knee extension, resulting in more force being transferred to the knee joint and its passive restraints.

| Effusion can detrimentally affect the function and outcome of the joint in a number of ways: |

|---|

| -Increasing intra-articular joint pressure -Altering quadriceps muscle recruitment -Decreasing the stability mechanisms around the knee -Altering limb-loading patterns |

Removing the effusion does make a demonstrable difference to quadriceps function. This can be a frustratingly slow process, however, and so a number of interventions should be prioritised:

- Regular assessment performed prior to loading the knee joint, and in the subsequent 24 hours – particularly if the load is new and more progressive.

- Remove the effusion if present. This can be done with conventional methods such as elevation, compression with donut felt, effusion massage and reduced weight bearing. There are also more medically directed interventions such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs) or direct needle aspiration if indicated. Removing the internal fluid will significantly reduce the internal pressure within the knee as well as improving quadriceps strength.

- Exercise selection – quadriceps setting exercises that are performed in positions of partial (20°) knee flexion or isometric squats in 20-30° flexion, will allow muscle recruitment without increasing the intra-articular pressure associated with full knee extension.

- Early pool work provides us with the opportunity to take advantage of hydrostatic pressure to aid with effusion drainage.

Reactivation of muscles in early phase rehabilitation

Since effective muscle function helps absorb joint loads, a restoration of contractile activity must be seen as a priority, and so in the early stages of knee rehabilitation the focus is on: Quadriceps setting exercises Quadriceps-hamstring co-contraction exercises Isolated hip muscle exercises (particularly gluteals and hip external rotators) in a non-weight bearing (lying down or sitting) or protected-weight bearing situation (altered gravity treadmills or pools if available). It should be noted that the LARS reconstructed knee usually does not need a major period of protected weight-bearing, so in most cases, weight bearing quadriceps, hamstring and hip muscle strength work can be included very soon after surgery. There are many ways to accelerate the return of muscle bulk and gross muscle strength in the early rehabilitation setting. Occlusion training and electrical muscle stimulation can be very helpful in gaining muscle hypertrophy in the early stages of rehabilitation where high mechanical and joint compressive loads are inappropriate (see figure 2). For a thorough piece on occlusion training, refer to an article written by Luke Heath in Issue 157 of Sports Injury Bulletin.

Figure 2: Occlusion training for the quadriceps

Restoring range of motion

Limitations in range of motion (ROM) are common following a LARS reconstructive procedure, particularly in terminal extension. The primary mechanisms that limit the final 5-10° of extension can be broken down into mechanical (intraarticular) and myogenic (muscle tone) reasons. Dependent on the cause, manual therapy aimed at restoring accessory joint motion, effusion aspiration, soft tissue massage, trigger point releases and dry needling / acupuncture may help correct ROM restrictions.

| To allow progression to phase 2 of rehabilitation, we suggest the following exit criteria are passed (this may be as fast as 2 weeks post operative): |

|---|

| 1. Resolution of active inflammatory process 2. Pain-free functional active knee ROM (may lack 5-10° of extension and 20° flexion) 3. Normalised pain-free walking gait 4. Good voluntary muscle action |

Phase 2 – strength and motion

The second phase of rehabilitation is geared towards the introduction of strength work. This can be broken down simply into kneedominant and hip-dominant movements. These are essentially exercises done in a sagittal plane and involve the combination movements of ankle dorsiflexion/ plantarflexion, knee flexion/extension and hip flexion/extension. In simple terms, examples of the following are:

- Knee dominant: single leg squat, single leg lunge, leg press, Bulgarian (rear foot elevated) squat, Nordic hamstring curls

- Hip dominant: Romanian deadlift, glute-ham raise, hip thruster

These are initially performed using bodyweight only and with slow controlled tempo. Load/speed and complexity is added as the athlete progresses through the rehabilitation setting. The key feature in this stage is that the joints of the lower limb (knee joint included) are engaging in a co-ordinated manner that satisfies the kinetic chain requirements of the lower limb.

The joints initially absorb force (slowly in the early stages of rehabilitation) through the eccentric component. They are then required to hold, stabilise and control a loaded position, before finally propelling away from the loaded position whilst maintaining kinetic chain alignment.

The benefit of a LARS reconstructed knee is the fact that no donor site morbidity exists as would be present in a PTB or hamstring graft ACL reconstruction. Therefore, strength work is usually progressed much quicker in a LARS reconstruction. Some rules/guidelines to follow when considering the implementation of these traditional clinical/gym based movements are:

- Propulsion/acceleration forces – The joints and movements involved in the propulsion phase of locomotion are ankle plantarflexion, knee extension and hip extension (triple extension phase). This capacity is generally the easiest and safest to develop early, involves concentric muscle force, and requires the least work capacity and the safest joint reaction forces.

- Absorption/deceleration forces – The joints and movements involved are ankle dorsiflexion, knee flexion and hip flexion (triple flexion phase). This capacity requires the highest amount of force production as the muscles are working eccentrically and the downward effect of gravity and the resultant upward ground reaction force are greatest. Joint stress on the knee is maximised and thus is the hardest to develop. However because knee injuries usually occur in the landing/ cutting/deceleration type situations, it is these absorbing/decelerating forces that need to be trained to a high level prior to return to competition.

- Early plyometrics – Introduction of higher intensity movements, with the aim of perfecting technique for latter stages (where load is increased). These can be added early in the rehabilitation setting via safe joint-sparing alternatives such as unloaded fast eccentric exercises and pool plyometrics.

- Bilateral transfer – Training the contralateral limb can result in measurable strength and performance gains in the affected limb. Early strength work on the unaffected side will assist in earlier functional recovery in the affected side.

| To allow progression to phase 3 of rehabilitation, we suggest the following exit criteria are passed (this can be as fast as 6 weeks post operative): |

|---|

| 1. Full resolution of any effusion 2. Full range of movement (although may lack 10% of flexion) 3. Good control of single leg squat 4. More than 70% hamstring and quadriceps strength compared to contralateral side |

Phase 3 – return to function

The third phase is an extension of the second. However, the emphasis is now on sport-specific movements that need to be retrained prior to return to full training and subsequent competition. This is the stage that is characterised by return-to-running protocols and the introduction of agility and cutting movements. There are a plethora of factors need to be considered and integrated into a return to running program.

Developing the capacity to decelerate

Getting the athlete to repeat box landings are helpful in training the ability to arrest body weight. The progression sequence for a LARS reconstruction would be;

- Two legged jumps onto a box

- Two legged jumps off the box

- One legged hops onto box

- One legged hops off the box

- One legged hops with increasing height (maximum height 40cm)

This progression should take place over the course of a month. Do not try to ‘tick all these boxes’ in too short a period, as the risk of developing patellar tendinopathy is high if there is a sudden spike in loading.

Clinicians also need to be acutely aware of the importance of well-structured running/agility programs that incorporate the development of the deceleration forces such as cutting, turning, slowing down, landing and pivoting. Generally speaking, the athlete should be exposed to a number of weeks of increasing volumes of acceleration, deceleration and top-speed drilling before integration into open-skilled training is considered.

To allow progression to phase 4 of rehabilitation, we suggest the following exit criteria are passed (this can be as fast as 9 weeks post operative):

- Maintenance of an effusion-free joint

- Full range of movement (may lack 10% flexion)

- Good control of single leg landing from a 40cm box

- More than 85% hamstring and quadriceps strength compared to contralateral side

- Good control of 50-degree change of direction to either side

- Return to more than 85% of pre-injury maximum running speed

Phase 4 – return to performance

In the final stage of rehabilitation and reconditioning, the athlete progressively returns to sport-specific skill training. In this stage, high-level rehabilitation exercises that incorporate functional kinetic chain integration (ankle, knee, hip, pelvis, spine and upper limb) need to be implemented in a manner that challenges the athlete’s proprioceptive abilities and reactive abilities. The purpose is to condition the neuro-sensori-motor system to a wide spectrum of unpredictable stimuli so that maximal ‘CNS wiring’ can occur. The variables that can be manipulated to provide broad spectrum challenges are:

- Surface – stable (floor) to unstable (sand, balance boards, trampoline, mats)

- Body movement – stable on feet to unstable (rolls to stand, jump variations)

- External load – eg cables, dumbbells, weight vests, asymmetrical weight barbells, kettle bells, suspension trainers, medicine ball

- Sensory cues – variations in responding to sound, vision and touch

- Speed – slow speed to fast movement

- Environmental obstacles – other athletes, cones, hurdles etc

There exists a plethora of different training modalities that an athlete may be subjected to in this stage of the rehabilitation/ reconditioning process. Two modalities that have been used to great effect are sand-based training and gymnastics – based training.

Sand-based training

A 5m x 10m sand pit can provide a fantastic and challenging rehabilitation environment for the knee-injured athlete. Simple drills that are also done in stable-base training (eg grass or gym) can also be used in the sandpit. The benefit of the sandpit is that due to the shifting surface, it provides a greater proprioceptive challenge. Furthermore, the sand absorbs much of the downward reaction force, which is a positive benefit to the load-compromised knee:

- Running drills – all of the running drills used in ground-based running can be used in a sandpit. Furthermore, as well as forwards running the athlete can perform backwards running. Carioca drills, stepping and cutting drills and lateral movement drills can also be performed in the sandpit.

- Jump, hop and landing drills – forward hops, sideways, lateral hops, two leg to one leg, single hops vs multiple hops are all variations that can be used.

- Sand displacement drills – using the planted feet, the athlete can be encouraged to ‘move’ through the sand by using a twisting motion to displace sand away from the feet. This encourages the development of hip/knee rotation, ankle stability and foot stability. The athlete can move forwards by stepping/lunging into the sand and then twisting the foot prior to the next step. Alternatively they can keep the feet buried and twist side to side to move laterally through the sand.

Trampoline drills

Full-size trampolines also provide a difficult balance environment for the knee injured athlete:

- Run and stop drills – have the athlete running on the spot and stop on an auditory or visual cue. This will not only develop reactive abilities to external stimuli, it will also create greater proprioceptive and balance integration due to the unstable surface the trampoline provides.

- Hop and landing drills – single hops, double-leg jumps, forwards, sideways, backwards are all variations that can be used with hop drills.

- Rolls to balance – forwards and backwards rolling to a squat stance or single leg stance provides an enormous strength, balance and range of movement challenge. Although not exactly specific in its application, the crossover effect of this type of balance training can provide immeasurable benefit to the knee injured athlete.

Return to contact training

Staging a knee-injured athlete back to a full competitive training situation requires a stepwise progression of drills and skills that resemble the demands of the competition, whilst still allowing appropriate protection of the knee at critical stages of recovery. A logical way to prepare the athlete to develop match readiness is to modify the training environment from safe and controlled situations initially, to more advanced game-specific events as they progress. For example, starting in kneeling positions and then progressing to standing, walking and running positions allows the athlete to confidently practice contact components without fear of further knee injury.

Functional tests

The highest risk for a knee injury is a previous knee injuryBritish Journal of Sports Medicine. 2006. 40(2): p. 158-162.. In order to do everything we can to reduce this risk to a minimum – and be confident that the athlete is not just fit to play but fit to perform – a series of functional sports-specific test should be employed. The test should be an objective, measureable and quantifiable test that includes an element of:

- Strength

- Agility

- Power

- Balance

- Neuromuscular status

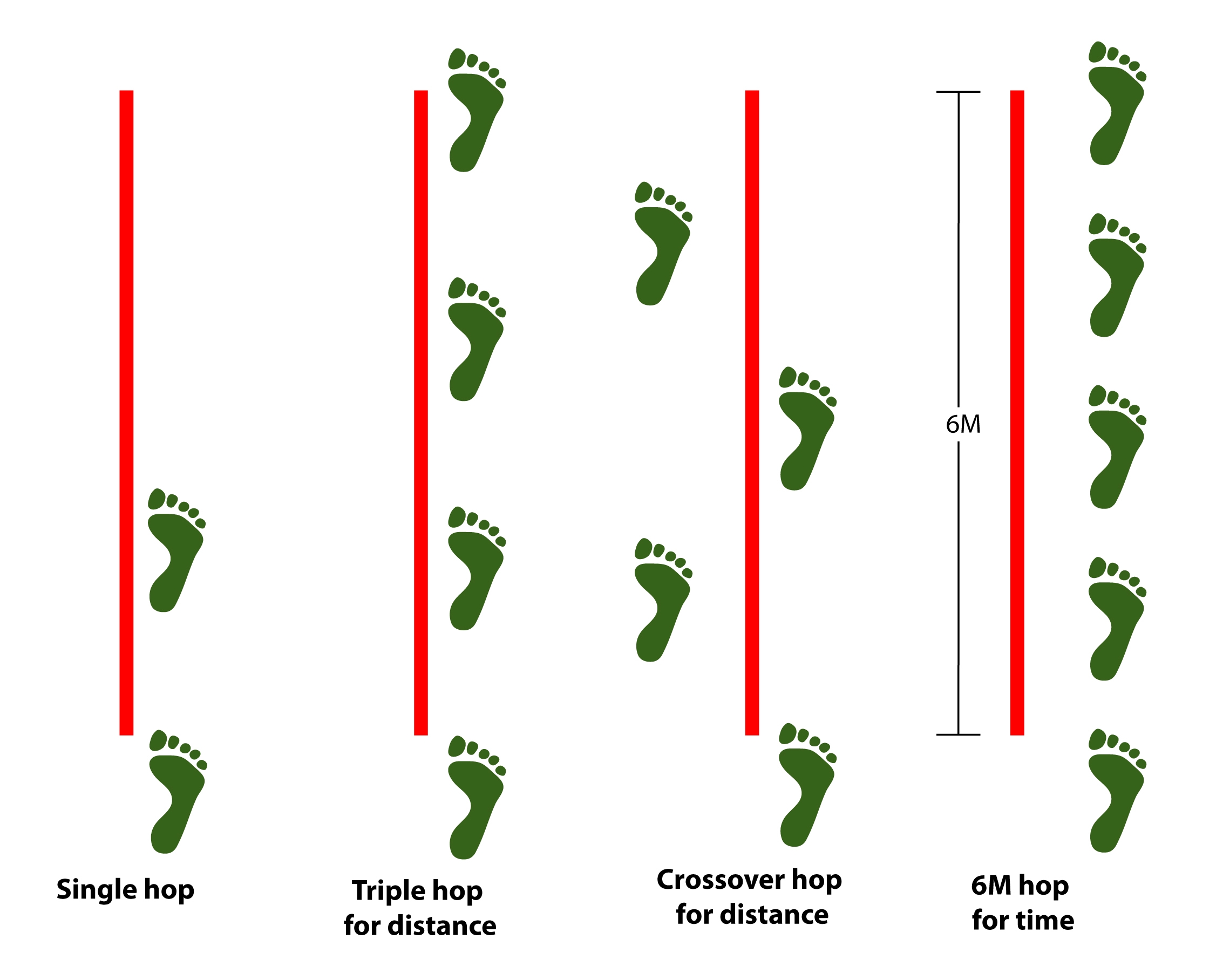

Figure 3: The four single-legged hop tests

The above factors can be incorporated into functional tests such as hops and agility/ movement tests. The more common hop tests include (see figure 3 above):

- Single hop for distance

- Triple hops

- Crossover hop

- 6-metre timed hop

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss these functional hop tests in detail. However Sports Injury Bulletin issue 141 describes these tests in detail and the reader is encouraged to review this piece for more detailed explanation regarding the validity and use of these hop tests.

| To allow progression to full competition, we suggest the following exit criteria are passed (this can be as fast as 14 weeks post operative): |

|---|

| 1. More than 90% of pre-injury hop distance and cross-over hop test results 2. Return to full sprint speed 3. Return to full acceleration and deceleration velocities 4. Full competence and confidence over the course of a prolonged period of competitive training (as reported by the coaching and support teams, as well as the athlete themselves) 5. More than 90% hamstring and quadriceps strength compared to contralateral side |

The load compromised athlete

Unfortunately for the athlete returning from a LARS reconstruction, the knee joint pathology needs to be respected for the remainder of the athlete’s career. This essentially makes the athlete ‘load compromised’ against a similar athlete with no previous history of knee injury. From a knee perspective, the practical interventions that need to be considered once the athlete is back to competition are:- Regular assessment of effusion, particularly after a major change has been implemented such as a new skill, extra load, plyometric type training, frequent exposure to competition/ training etc.

- Regular assessment of functional tests to ensure the athlete stays within acceptable levels.

- Load monitoring – this can be direct volume and impact monitoring using GPS or, if unavailable, carefully selecting the training sessions the athlete will be involved in. Athletes may need to miss the occasional session to allow knee joint recovery.

- Regular soft tissue therapy (to ensure the myogenic elements of tissue are not reacting adversely to load).

- Education for both athlete and coaches. All interested parties need to be aware that the knee may require periods of de-loading to restore a healthy homeostasis.

Summary

A LARS reconstructed knee is a controversial topic and is still relatively new and unknown in the world of sports medicine. Further long-term studies are needed to evaluate the implications regarding re-injury rates and other complications following a LARS reconstruction. However, the limited available empirical research does show promise in returning an athlete back to full competition status much faster than traditional ACL reconstructions.Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.