You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Masterclass: Femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) - Part II

In the first part of this 2-part article on femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI), Chris Mallac discussed how FAI can lead to insidious onset groin pain and damage the hip joint labrum, leading to early arthritic changes. Given that conservative management usually fails in young athletes and requires surgery, part two describes the post-operative rehabilitation period required to take an athlete back to full competition.

Hip injuries plague squatting athletes as they did goalie Patrick Roy during the 2002 season.

The post-operative rehabilitation period is highly dependent on the extent of pathology and the subsequent procedure; weight-bearing progression is therefore variably reported in the literature. Simple labral debridement and re-contouring of the acetabular rim usually allow the athlete to bear weight as tolerated, with an emphasis on early range of motion and joint stability exercises.

If the labrum is surgically fixed, then protected weight bearing is encouraged to allow the repair site to be protected during the early healing phase. Also, avoiding extremes of flexion (past 60°) and internal/ external rotation for the first 4 to 6 weeks is important to protect the repaired labrum. Any positions that potentially create an impingement and increase inflammation should be avoided. These include:

- Deep squatting

- Prolonged sitting

- Low couch sitting

- Lifting off the floor

- Pivoting on a fixed foot

These positions are more safely tolerated after the six-week post-operative period. However, due to the range of hip flexion limitations imposed in the first six weeks, usual activities of daily living are quite limited, making return to work and daily chores difficult, if not impossible, in the first few weeks after surgery. Therefore, the post-surgical patient does need to make significant lifestyle changes, and they need assistance in the first six weeks after surgery.

Mention must also be made regarding special precautions in certain types of FAI procedures. Reshaping of the femoral head-neck junction can weaken the femoral neck, so special care must be taken in the postoperative period. Fracture of the femoral neck is an unlikely but potentially serious complication following a reshaping procedure. The athlete may be allowed to bear full weight, but crutches are needed to avoid twisting movements during the first four weeks following surgery. High-impact activities and high torsion movements should be avoided in the first three months, as bone remodeling takes around three months to achieve full structural integrity. Furthermore, if microfracture of the femoral head is also performed for femoral head cartilage defects, then the athlete should be restricted to partial weight-bearing for two months in order to optimize the early maturation of the fibrocartilaginous healing response.

Key points

- Weight bearing status is dependent on the type of reshaping procedure, whether the labrum has been repaired, and also what the surgeon prefers.

- Avoid hip flexion past 60° in the first 4-6 weeks.

- Avoid extremes of rotation.

Post-surgical rehab

Rehabilitation protocols provided in the literature tend to be quite generic in their advice and, at best, describe broad transitional periods during the rehabilitation process. They usually describe the transition in weight-bearing status, the progression of gait through walking to running, and give general guidelines as to how to and when to progress activity based on a time dependant approach.

They then progress, describing transitions into twisting and impact activities – usually described as starting at three months following surgery – and generally, the advice is that the speed with which the athlete advances is variable and may require another 1 to 3 months for full return depending on the sport. Athletes are generally advised that return to sports following surgical correction of FAI can take 4 to 6 months. However, it is crucial that progression through rehabilitation stages is driven more by subjective and objective measures during the transition periods. This allows the athlete and therapist to monitor load (type and volume) and determine whether the joint structures are able to withstand changes in load safely.

Wahoff et al. (2014) have offered some criteria that can be used to guide the transition from one stage to the next(1). They describe their rationale and provide a complete description of the mentioned tests. In essence, the exit criteria they offer in each stage are as follows;

| Exit criteria for stage one — immediate post-surgical rehabilitation |

|---|

|

1. Minimal healing time determined by procedure and surgeon 2. Score of under three on a verbal 11-point scale 3. Circumferential measure within 1cm of the healthy side, measured around the highest point of thigh 4. Passive Range Of Movement (PROM) within 90%, except the following limited to ext 10, ext rot 15, flex 110 5. Ten correctly performed prone hip extension exercises, active hip abduction tests, and Level II Sahrmann abdominal exercises (see box 1 below)

See the review by Wahoff et al. (2014) for a complete description of these tests and criteria. |

| Exit criteria: stage two — sub-acute rehabilitation |

|---|

|

1. ABD, ADD, INT ROT PROM within normal limits, Ext 20, Flex 120-130, EXT ROT and FABER 75% 2. Symmetrical bilateral leg squat to 70° knee flexion 3. 30 correct prone hip extensions 4. Uncompensated single leg stance, active hip flexion in contralateral single leg stance, pelvic rotation on single leg stance 5. Normal uncompensated gait for 10 minutes |

| Exit Criteria: Stage Three — Return to Sport 1 |

|---|

|

1. HOS ADL minimum score 89 2. 10 x 70° single leg squat without kinetic collapse 3. 10 x 80° step-ups and step-downs without kinetic collapse 4. Side plank test maintained for 60 seconds 5. Tolerates sports-specific tasks at 0-1 Borg Scale without kinetic collapse Note — the HOS ADL has been described and validated extensively in the literature. For a sample of this questionnaire, see Martin et al. (2006) |

| Exit Criteria: Stage Four — Return to Sport 2 |

|---|

|

1. Vail test score 10/20 or 50% 2. Greater than 90 % dynamometer symmetry 3. Under 4cm asymmetry with Y balance test or sum of excursion on SEBT over 94% 4. Tolerates sports-specific tasks on a 2-4 Borg scale without kinetic collapse Note — for the Vail Test, see Garrison et al. (2012). This is a series of multiplanar functional activities that can be used to assess return to sport. It involves four tests; single leg squat for 3 min, lateral bounding for 100 seconds, diagonal bounding for 100 seconds, and forward lunge onto height for 2 minutes. |

| Exit Criteria: Stage Five — Return to Sport 3 |

|---|

|

1. Vail test score 20/20 2. Greater than 85% LSI on single-leg hops 3. Less than six flaws during the 10-sec tuck jump 4. Tolerates sports-specific tasks on a 5-7 Borg scale without kinetic collapse |

| Exit Criteria: Stage Six — Return to Sport 4 |

|---|

|

1. HOS ADL minimum score 96 2. Greater than 92% LSI on single leg hops 3. Less than 10% side-to-side difference with the modified T-test 4. Tolerates sports-specific tasks on 8-10 Borg scale without kinetic collapse |

Box 1: Sahrmann Abdominal Exercise Progression Level 2

Starting position, Lying on your back with your knees bent (see figure 1). Movement:

Tighten the abdominals and slowly lift one leg in toward the chest, keeping the knee bent (see figure 2).

Raise the other leg in the same manner. Keeping knees bent (see figure 3).

Slowly lower the first leg to the starting position (see figure 4).

Then repeat the same with the other leg.

Figure 1: Start position

Figure 2: Leg lift

Figure 3: Both legs raised

Figure 4: Return of a single leg

In order to progress through the six described stages, the athlete will undergo extensive physiotherapy, focusing on hip range of movement exercises, manual therapy and trigger point releases, active stretching, possibly deloaded activities such as hydrotherapy or Alta G walking/ running and robust hip rotator and gluteal strengthening exercises. Much of this will be ‘controlled’ and directed by the wishes of the surgeon as they will provide the framework on when and what happens in terms of loading. However, more direct physiotherapy interventions have been devised to guide the physiotherapist through the rehabilitation protocol. The Takla-O’Donnell Protocol (TOP) is a validated physiotherapy intervention program that can be used to rehabilitate the arthroscopically managed FAI patient (see box 2)(2).

Box 2: The Takla-ODonnell Protocol (TOP)

1. Education. This is done pre-surgery and educates the patient as to the limitations they can expect post-surgery.

2. Manual Therapy. Trigger point work on hip muscles as well as lumbar spine mobilizations.

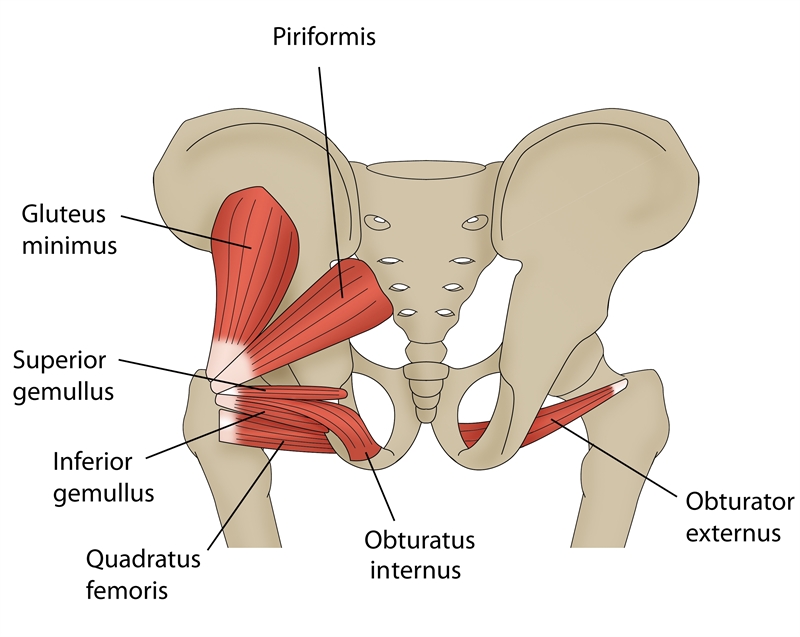

3. Deep hip rotator strengthening. This is a seven-stage progressive protocol that trains the deep hip rotators such as the gemellus group, obturator group, and quadratus femoris.

4. Stretches and range of movement. This includes hip flexor stretches, posterior hip capsule stretches (starting at four weeks), and quadruped hip flexion-extension exercises.

5. Gym and aquatic programs. The progression from gentle pool work to cycling and then to gym work.

6. Return to sports guidelines that can be incorporated at 12 weeks post-operative.

7. Outcome measures using recognized hip outcome measure protocols such as The International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33), Hip Outcome Scale (HOP), and Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS)

Hip muscle control

The focus of the remainder of this article will be to outline some common yet effective hip-strengthening exercises that may be used to progress hip muscle control through the rehabilitation stages. Regaining hip muscle strength, particularly in the deep hip external rotator group, is imperative in the FAI-recovering athlete. Good muscle strength and endurance in these muscle groups will ensure adequate hip joint compression occurs with movement to reduce any shearing effect between the head of the femur and the acetabulum(3)..

The muscle groups needing attention are (see figure 5):

- Posterior fibres Gluteus Medius (PGMed)

- Gluteus minimus

- Superior and Inferior Gemellus

- Internal and External Obturator

- Quadratus Femoris

- Piriformis

Figure 5: Muscle groups requiring attention in FAI

There is a plethora of exercises that can be used to strengthen the hip joint musculature. The chosen ones below are a sample of some effective exercises that can be used throughout the rehabilitation stages. However, the key requirements of the included exercises are:

- Performed in neutral hip positions to no more than 60 degrees hip flexion. This range of movement protects the hip joint from any potentially damaging impingement.

- Minimal rotation of the hip, allowing them to be used in most stages of the rehabilitation process.

- Performed isometrically or using small oscillating concentric/eccentric contractions – to contract and hold to keep the hip joint compressed and stable.

This represents the way these muscles work in human function.

Non-weight bearing (early stage)

Prone hip rotation (see figures 6 and 7)

- Lying face down on a plinth (or floor), bend the knee to 90 degrees keeping the knee in line with the hip.

- Fix a luggage belt around the thighs to prevent the thighs from moving into abducted positions.

- Attach a theraband to the ankle and fix it so that the direction of force is pulling the ankle away from the body. This creates an internal rotation force.

- Either simply hold the tube (isometrically), or allow the foot to move out and then in no more than 6 inches in each direction, thereby imparting a small oscillating movement to the hip joint rotation (concentric and eccentric contractions).

- Perform either set of sustained holds for 30 seconds or perform small oscillating movements for 30 seconds with holds in different points of the range.

Figure 6: Prone hip rotation start position

Figure 7: Prone hip rotation finish position

The muscles that work in this position are the hip external rotators, eccentrically controlling the limb as the foot moves outwards (internal hip rotation). They then work concentrically to pull the foot back inwards (towards external rotation). The client can also palpate the posterior hip muscles to feel the contraction occurring. The benefits of this exercise are;

A. It is performed in neutral hip flexion/extension, thereby protecting the repaired hip joint from hip flexion.

B. Small amounts of rotation again protect the hip.

C. It is non-weight-bearing.

D. It involves isometric/concentric/ eccentric in neutral hip joint ranges.

Seated hip rotation (see figures 8 and 9)

- Sit on a plinth/high table.

- Again affix a luggage belt around the thighs to prevent the leg from being pulled into abduction. Rather than sitting upright, allow the pelvis to rock back into a posterior tilt and lean backward slightly. This will allow the hip joint to sit safely at 60 degrees rather than 90 degrees.

- Attach a theraband to the ankle and fix it so that the direction of force is pulling the ankle away from the body. This creates an internal rotation force. Either simply hold the tube (isometrically), or allow the foot to move out and then in no more than 6 inches in each direction, thereby imparting a small oscillating movement to the hip joint rotation.

- Perform sets of sustained holds for 30 seconds or perform small oscillating movements for 30 seconds with holds at different points of the range.

Figure 8: Seated hip rotation start position

Figure 9: Seated hip rotation finish position

The muscles that work in this position are the hip external rotators eccentrically controlling the limb as the foot moves outwards (internal hip rotation), and then they work concentrically to pull the foot back inwards (towards external rotation). The benefits of this exercise are;

A. It is performed in reduced hip flexion, thereby protecting the repaired hip joint from hip flexion.

B. Small amounts of rotation protect the hip.

C. It is minimal weight-bearing on the hip joint.

D. It involves isometric/concentric/ eccentric in controlled hip joint ranges.

Partial weight bearing

All fours hip rotation (see figures 10 and 11)

- Kneel on a plinth/floor and affix a luggage belt around the thighs to prevent the leg from being pulled into abduction.

- Position the pelvis well in front of the knees to avoid 90 degrees hip flexion. This will allow the hip joint to sit safely at 60 degrees rather than 90 degrees.

- Attach a theraband to the ankle and fix it so that the direction of force is pulling the ankle away from the body. This creates an internal rotation force. Either simply hold the tube (isometrically) or allow the foot to move out and then in no more than 6 inches in each direction, thereby imparting a small oscillating movement to the hip joint rotation.

- Perform sets of sustained holds for 30 seconds or perform small oscillating movements for 30 seconds with holds at different points of the range.

The muscles that work in this position are the hip external rotators eccentrically controlling the limb as the foot moves outwards (internal hip rotation), and then they work concentrically to pull the foot back inwards (towards external rotation).

The benefits of this exercise are;

A. It is performed in reduced hip flexion, thereby protecting the repaired hip joint from hip flexion.

B. Small amounts of rotation again protecting the hip.

C. It is minimal to moderate weight-bearing on the hip joint

D. It involves isometric/concentric/ eccentric in controlled hip joint ranges.

Figure 10: All fours hip rotation start position

Figure 11: All fours hip rotation finish position

Seated hip abduction (see figures 12 and 13)

- Sitting on a high box/chair (high enough so the hip is no more flexed than 60 degrees) place a theraband tube around the knees. Ensure some weight remains on the feet (around 50% on the feet and 50% on the buttocks).

- Start with the feet together, then slowly move the knees apart whilst the feet stay together. This movement combines hip abduction with hip external rotation.

- Perform small oscillating movements for 30 seconds.

The benefits of this exercise are;

A. It is performed in reduced hip flexion, thereby protecting the repaired hip joint from hip flexion.

B. Small amounts of rotation again protecting the hip.

C. It is moderate weight-bearing on the hip joint representing a progression from the previous exercises.

D. It involves isometric/concentric/ eccentric in controlled hip joint ranges.

Figure 12: Seated hip abduction start

Figure 13: Seated hip abduction finish

Full weight bearing

Sideways walks lotus position (see figures 14 and 15)

This is performed more upright with the knees forward, loading the quadriceps more than the hip extensors. However, the pull of the theraband on the knees creates an adduction/internal rotation force on the hip, thereby incorporating the posterior hip rotators.

- In full weight bearing, semi-squat position, place a theraband around the knees.

- Start with the feet hip-width apart and then step sideways so the feet are 10-12 inches apart. Remain in the hip flexed position, as this will maintain gluteal and hip rotator activation. Aim to keep the feet either facing directly forwards or even slightly turned outwards into external hip rotation.

- Bring the stance leg back to the lead leg and then take another step.

- Work on 20 steps sideways, then return the way you came taking 20 steps.

- Always remain facing the same direction. Therefore each leg acts as the lead leg and then trail leg.

Figure 14: Sideways walk (lotus position) starting posture

Figure 15: Sideways walk (lotus position) finish posture

Sideways walks sumo position (figures 16 and 17)

- With hands on hips, bring the knees back so the shins remain more vertical and the hip is more flexed. This loads the hip extensors over the quadriceps.

- Perform the movement as described above for the lotus walk.

- The key difference with this position is that the greater hip flexion angle will load the gluteals over the quadriceps, and the greater hip flexion angle makes it more appropriate for later stages of rehabilitation (12 weeks onwards).

Figure 16: Sideways walk (sumo position) start posture

Figure 17: Sideways walk (sumo position) finish posture

Short step triple flexion/extension drill (see figures 18 and 19)

This is a great lead-up movement to generate the strength and control for the hip drive prior to restarting running in the athlete:

- Stand on a small step (low enough to keep the hip flexed no greater than 60 degrees) with the hands on the wall.

- Affix a theraband either under some weights on the floor or tied to an immovable object behind the patient. The band needs to be positioned so that its direction of pull is at 45 degrees to the affected hip.

- The band is placed as high as possible in the groin area. This direction of pull on the pelvis will attempt to create a hip flexion/ adduction/internal rotation force. To prevent this, the hip extensors/ abductors/external rotators will need to contract.

- Drive the opposite leg upwards into hip and knee flexion, thereby moving the stance leg into extension at the hip and knee. Hold the position for 1-2 seconds and then slowly descend back to the start. Perform three sets of 10 repetitions.

Initially, this movement is only performed standing on the affected hip. As the patient progresses and is allowed to attain more hip flexion (past 90 degrees), then the other leg can now be worked to gain some muscle symmetry.

Figure 18: Triple flexion/ extension drill start position

Figure 19: Triple flexion/ extension drill finish position

Summary

Hip joint injuries in the athlete can occur in many ways. Hip joint labral tears, capsule sprains, muscle and tendon injuries, and bony architectural problems such as FAI can all lead to debilitating hip pain. FAI is a genuine concern for the athlete as the presence of a bone abnormality can lead to painful hip impingement, damage to the acetabular labrum and early-onset degeneration. If the athlete suffers debilitating pain that affects competition, then the options are either to cease competition altogether or have the FAI surgically corrected. Once corrected by the surgeon, regaining full movement and muscle strength and eventual sport-related functional skills will take time. Hip rotator muscle strengthening should form the basis of all managing post-surgical FAI issues.

References

- International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 9(6); pp 813-826

- Arthroscopy. 2006;22(12):1304-1311

- Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7(1):20-30

Further reading

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.