You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Understanding Posterolateral Corner Injuries in Sport

The posterolateral corner is known as the dark side of the knee. James Nowosielski sheds light on PLC injuries in sports and helps clinicians understand the biomechanics, assessment, and treatment.

Los Angeles Rams wide receiver Austin Trammell is upended by Denver Broncos safety JL Skinner as safety Devon Key defends in the third quarter at Empower Field at Mile High. Mandatory Credit: Isaiah J. Downing-USA TODAY Sports

Injuries are commonplace in sports. On average, professional male football athletes will suffer 8.1 injuries per 1000 hours of exposure. During game time, this increases significantly to 36 injuries per 1000 hours, almost ten times higher than the prevalence of injuries sustained in training (3.7 per 1000 hours). Lower limb injuries are the most common at 6.8 per 1000 hours(1).

If clinicians encounter individuals who engage in or participate in any sport, they will likely come across cases of ACL or meniscus injuries. Furthermore, many of these clinicians will also encounter individuals with osteoarthritis. Some injuries, however, have a considerably lower profile.

Posterolateral corner (PLC) injuries may be more common than clinicians think, with up to 16% of all knee ligament injuries affecting the PLC complex. Given that they are usually associated with ACL or PCL injuries, a missed diagnosis can lead to the failure of any reconstruction, which would understandably be catastrophic for the athlete.

Approximately 7-16% of knee ligament injuries are to the PLC complex. The incidence of isolated PLC injuries may be as high as 28%. Still, most will accompany an ACL or PCL tear and can contribute to ligament reconstruction graft failure if not recognized and treated(2). Posterolateral corner deficiency may lead to residual instability and chronic pain due to biomechanical overloading when not appropriately treated(3). Therefore, clinicians must maintain a high suspicion when assessing traumatic knee injuries.

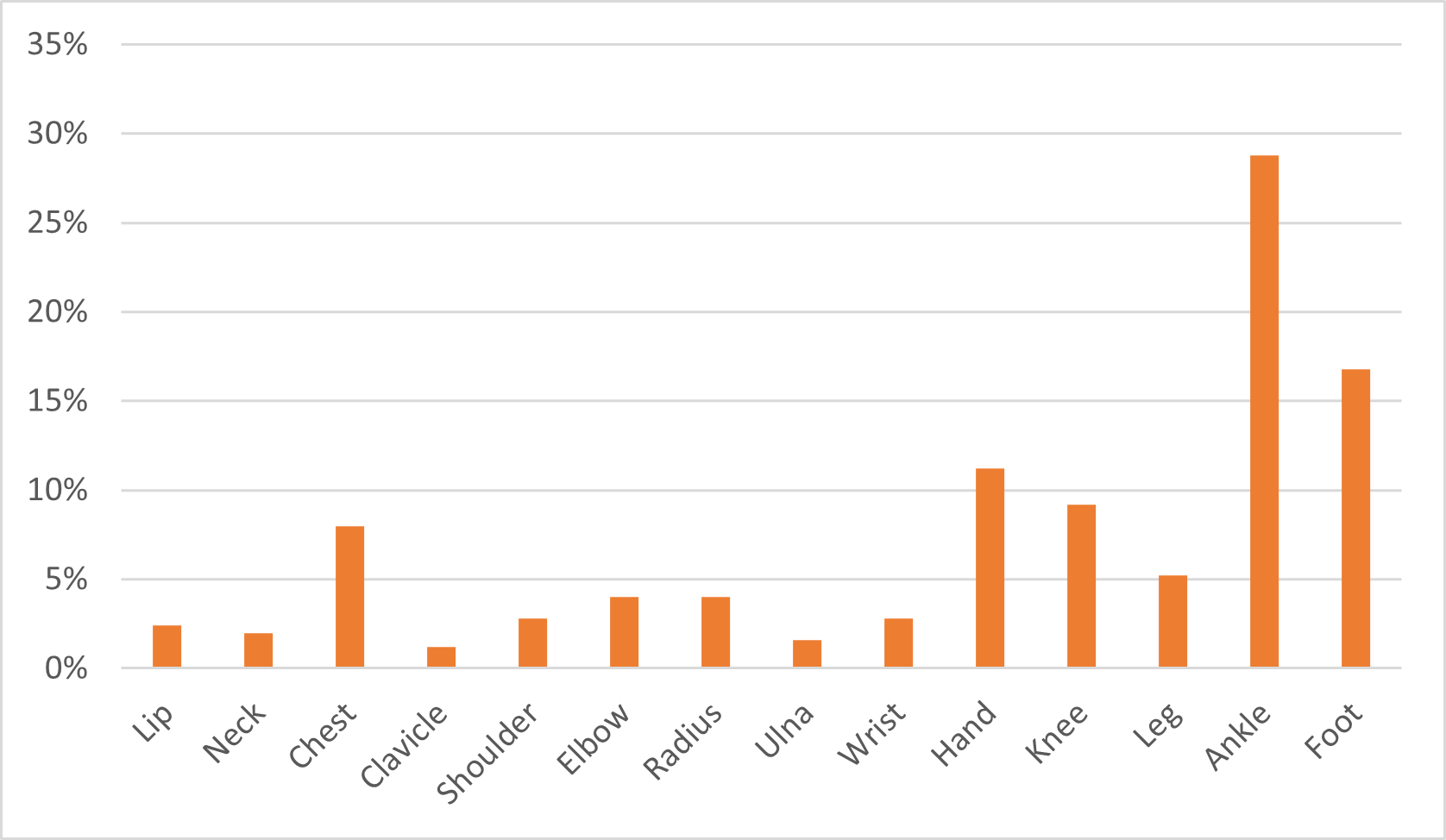

Table 1: Prevalence of sporting injuries(4).

Anatomy

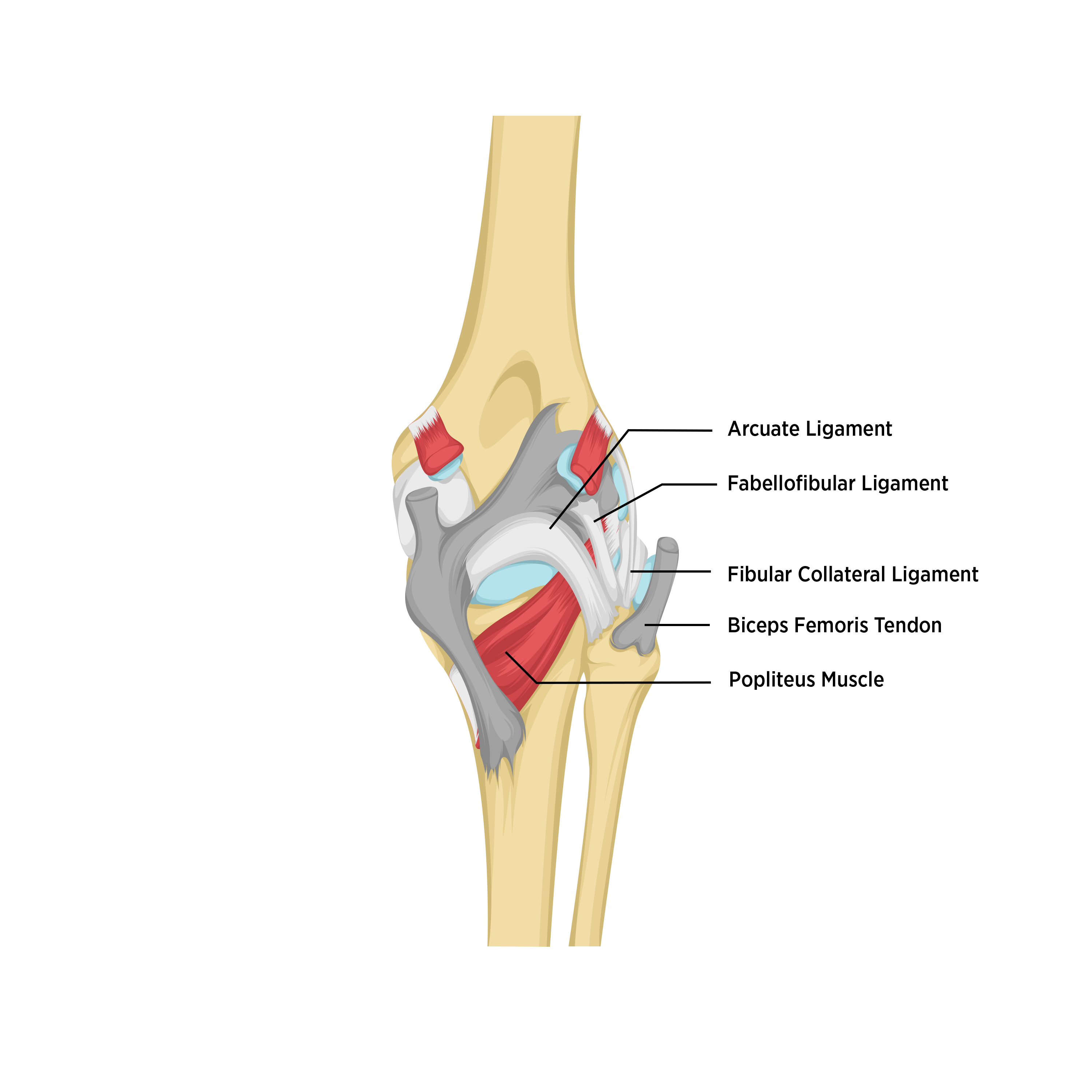

The posterolateral complex consists of a group of dynamic and static stabilizing structures that work together to maintain the posterolateral stability of the knee (see figure 1).

The static structures responsible for stability include the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), the popliteofibular ligament (PFL), and the fabellofibular ligament. On the other hand, dynamic structures are the biceps femoris tendon, the iliotibial band, and the popliteal muscle-tendon complex. Among these, the biceps femoris tendon functions as a dynamic structure located at the posterolateral aspect of the knee, generating flexion force when it contracts. Although it doesn’t prevent posterior dislocation of the lateral tibial platform, it acts as a static structure to restrict anterior movement of the tibia when the knee is fully extended.

The iliotibial band has a different course depending on the knee position; it runs from the posterior side of the lateral femoral epicondyle during flexion greater than 40° and from the anterolateral side when the knee is extended. Generally, it is not considered a posterolateral structure. In severe lateral structural injury cases, the iliotibial band may also sustain damage, often leading to an avulsion fracture of Gerdy’s tubercle.

Both static and dynamic structures stabilize the knee by restraining varus, external rotation, and combined posterior translation with external rotation.

Mechanism of Action

Posterolateral corner injuries can occur due to direct or indirect trauma to the knee. The most common mechanism involves a combination of forces, such as a direct blow to the inner knee, a sudden twisting motion, or a hyperextension injury. Researchers from the University of Minnesota in the USA demonstrated the incidence of PLC knee injuries with acute knee ligament injuries with hemarthrosis is 9.1%. They confirmed that PCL and posterolateral corner injuries are often combined with other ligament injuries(5).

Assessment

Correctly identifying PLC injuries is crucial for optimal recovery. While the severity of symptoms can vary, some common signs of a PLC injury include:

- Pain and tenderness on the outer side of the knee joint.

- Swelling and inflammation.

- Instability or feelings of the knee giving way.

- Restricted range of motion.

- Difficulty walking, running, or pivoting.

- Audible popping or clicking sounds during knee movements.

These symptoms are associated with many other injuries, such as meniscal tears, osteo- and rheumatoid arthritis, and cruciate or collateral ligament tears, amongst many others. It’s essential to discuss the nature of the injury with the athlete, the mechanism of injury, and the onset and progression of symptoms. This information helps clinicians establish a preliminary understanding of what’s going on. Then, they should perform an in-depth examination of the knee joint with special attention given to assessing stability, range of motion, and tenderness or swelling. Specific tests, such as the posterolateral drawer, dial, and external rotation recurvatum tests, assess ligamentous integrity and stability.

Posterolateral Corner Injury Mechanisms

- A blow to the anteromedial knee

- A varus blow to a flexed knee

- Contact and non-contact hyperextension injuries

- An external rotation twisting injury

- Knee dislocation

Along with the ligamentous injury, it is not uncommon for PLC injuries to be associated with neurovascular injuries, such as common peroneal nerve (15-29% of all PLC injuries). Ultimately, the special tests help identify possible PLC injury, but MRI is required to confirm a diagnosis and remains the gold standard in traumatic knee injury assessment.

Posterolateral drawer test

The starting point for this test is similar to the posterior drawer test but with the foot externally rotated about 15°. Here, a combined posterior force and external rotation torque is applied to the tibia to determine the amount of rotation of the tibial tubercle that occurs compared to the distal femur. A positive posterolateral drawer test indicates a grade III PLC injury(6).

Dial test

The clinician flexes the athlete’s knees to 30° with both hands cupping his heels (prone or supine). Then, the clinician applies a maximal external rotation force and compares the foot-thigh angle on both sides. Then, they flex the knees to 90°, and again, apply an external rotation force and measure the foot-thigh angle. A positive test is an increased foot-thigh angle on the affected side(7).

External rotation recurvatum test

During this test, the clinician determines if there is an increase in knee hyperextension compared to the contralateral side. They perform the test by applying a stabilizing force just above the knee while lifting the big toe to assess the amount of knee recurvatum present(6).

As with many injuries, MRI is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis. It provides a detailed visualization of the PLC structures, revealing any tears, sprains, or associated injuries(8).

Treatment

As with any injury, the treatment of PLC injuries depends on numerous factors, including injury severity, the athlete’s age, overall health, activity levels, and other athlete-specific intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Although most do, not all PLC injuries require surgery, and conservative management may be appropriate. Individualized rehabilitation involves strengthening, range of motion, and proprioceptive exercises to promote healing and restore function. In the initial healing stages, a knee brace provides stability.

However, surgical intervention is likely necessary when conservative methods fail or for more severe PLC injuries. The specific surgical procedure will depend on the extent and nature of the injury and may involve ligament repair, reconstruction, or stabilization.

Regardless of the treatment approach, a structured rehabilitation program is crucial for optimal recovery. Physiotherapy will focus on strengthening the affected structures, improving the range of motion, restoring balance and proprioception, and gradually reintroducing sports-specific activities. Athletes should work closely with their rehabilitation team to ensure a safe and gradual return to sports, following a step-by-step progression that considers functional stability, strength, and physiological and psychological readiness.

Clinicians should introduce sports-specific testing when an athlete nears returning to sports. This will significantly reduce the likelihood of the athlete reinjuring once they return to playing their chosen sport. Clinicians must understand the demands of the sport when developing rehabilitation programs and subsequent return to sports testing. For example, the demands of football are not the same as those of cricket. Any testing should be functional and involve sport-specific movements. Football might involve forward and lateral running, cutting and pivoting drills, and kicking. In contrast, a bowler in cricket will be more focused on forward running and can confidently decelerate on their affected side.

Conclusion

Posterolateral corner injuries can significantly impact an athlete’s performance and well-being. By understanding the mechanism of injury, recognizing the symptoms, and using appropriate diagnostic and treatment strategies, athletes and clinicians can effectively manage these injuries to get athletes back to the top of their game as soon as possible. Early diagnosis, prompt and proper treatment, and comprehensive rehabilitation are essential to facilitate a successful recovery and enable athletes to return to their sports activities confidently.

References

- Br J Sports Med. 2020; 54(12):711-718

- Am J Sports Med. 1999; 27: 469

- Arthroscopy Tech. 2018; 7(2): 89-95

- Intl J Surg Med. 1970; 3(1): 45-45

- Arthroscopy. 2007; 23(12): 1341-1347

- Clin Ortho Related Res. 2007; 147: 82-87

- Am J Sports Med. 2008; 36(3): 577-94

- Acta Ortopédica Brasileira. 2014; 22: 124-126

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.