Illiotibial band syndrome: diagnosis and treatment

In some athletes, repeated knee flexion causes the illiotibial band (ITB) to produce friction over the lateral femoral condyle (LFE), or compression of the tissue underneath it. That tissue could be a fat pad or an outcropping of the synovial lining. Whether the cause is friction or compression, or the tissue is adipose or synovial, is really academic. The end result is the same: persistent lateral knee pain that can side-line an athlete.

Functional anatomy

Every gait cycle requires an abduction moment during unilateral stance. As the weight transfers to the single leg, the posterior portion of the gluteus medius and the entire gluteus minimus produce force vectors parallel to the neck of the femur and stabilise the femoral head within the hip socket. The anterior and middle fibers of the gluteus medius, with their vertical force production, initiate the abduction moment at the femur, which is fully realized with the activation of the tensor fascia lata (TFL) (see figure 1).To resist adduction and slow forward progression of the stance leg, these muscles must fire eccentrically and sequentially. When this process is imperfect (for example due to sub-optimum hip biomechanics), ITB is activated in order to assist with abduction. However, while it anchors fibres from the abductor muscles, ITB itself is not a muscle and thus has limited elasticity. The critical point in the gait cycle where the lateral hip muscles are most active coincides with the knee angle that brings the ITB closest to the LFE(1). Therefore, it is easy to see how any dysfunction at the hip strains the ITB and causes pain at the knee.

Figure 1: Force vector direction of the gluteus medius, minimus and TFL

Diagnosis

Clinicians should suspect ITB syndrome in any athlete who presents with sharp or burning lateral knee pain 2-3cm proximal to the knee joint near the LFE(2). The area may be somewhat swollen or exhibit crepitus or snapping during knee flexion (see table 1). The clinical exam should include full evaluation of the strength and range of motion of both legs.Several clinical diagnostic tests can elp determine the presence of ITBS (see figure 1). The Noble compression test attempts to illicit pain in the ITB at 30 degrees of knee flexion when it is closest to the LFE. The Thomas test assesses flexibility in the ITB and the TFL, along with the quadriceps and hip flexors, while the Ober flexibility test isolates the ITB.

Clinicians should assess the active and passive range of motion of the entire hip joint, observing any tightness in the gluteal muscles. Myofascial constrictions should also be identified and trigger points noted especially ones that refer pain to the lateral thigh or knee.

Tightness in areas besides the hip can also functionally affect the ITB. Examples include tightness in the gastrocnemius and soleus, which decrease closed chain dorsiflexion and therefore increase pronation and knee flexion. Excessive pronation increases internal rotation of the tibia, knee valgus and hip adduction, especially in the presence of weak hip abductors. A leg length discrepancy greater than one centimetre produces a similar effect and therefore should be corrected, along with any foot deformities, with an orthotic insert.

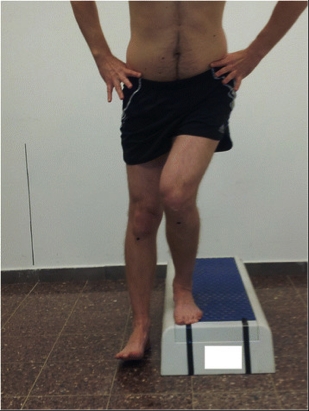

Clinicians should test functional stability and muscle firing patterns at the hip using the step down, unilateral knee flexion, or Trendelenburg test (see figure 2). Further functional tests, such as the single-leg balance reach tests assess movement and control in both frontal and sagittal planes of movement. Evaluating running gait to detect imbalances that occur with fatigue is also recommended. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show thickening of the ITB and fluid accumulation under the ITB near the FLE; however, it is rarely used to diagnose ITB syndrome(3).

| Grade I | Generalized lateral knee ache after training, which resolves with rest. |

| Grade II | Specific lateral knee pain at end of training activity that usually resolves with rest and does not affect performance. |

| Grade II | Lateral knee pain at onset of activity that interferes with performance. |

| Grade IV | Lateral knee pain limits training and is felt during activities of daily living. |

| Grade V | Lateral knee pain prevents normal training activities and interferes with activities of daily living. |

Figures 2a – 2e: Clinical tests used to reproduce pain; assess the flexibility of the ITB and the surrounding muscles; and evaluate strength and functional stability of the hip

2a: The Noble compression test

Attempts to reproduce the pain of ITBS. Position the athlete in side-lying, flex the involved knee to 90°and apply pressure just proximal to the LFE as you passively extend the knee. Pain, especially around 30°of flexion indicates ITBS.

2b: the Thomas test

The athlete lies on his back with hips at the edge of the exam table and brings both legs to his chest. Drop the involved leg off the table, keeping both low back and sacrum flat against the table. If the hip does not extend to 0°, then there is tightness in the illiopsoas muscles. If the thigh extends to 0°but the knee extends beyond 90°, then the rectus femoris is tight. If the hip does not fully extend but the knee flexes to near 90°, then there is normal length in the rectus femoris, but not in the illiopsoas. The illiopsoas and rectus are both tight if the hip remains flexed and the knee extends. Abduction or tibial external rotation of the involved leg as it extends indicates ITB tightness.

2c: The Ober test

Specifically tests the flexibility of the ITB. In side-lying with hips near the back edge of the table flex and the involved knee to 90°, abduct and extend the involved hip, and stabilise the pelvis with the other hand. Allow the hip of the involved leg to passively adduct while in the extended position. If it adducts past horizontal, then there is minimal tightness in the ITB. If only able to adduct to horizontal, then there is moderate tightness. Adduction that does not reach horizontal indicates significant tightness in the ITB.

2d: Lateral step down test

A Trendelenburg sign at the hips (hip hike on standing leg, hip drop on lowered leg), femoral adduction, and internal rotation, indicate gluteus medius weakness.

2e: Single leg balance ipsilateral reach test and overhead reach test

These measure the strength of the glutes in the sagittal and frontal planes and the leg’s ability to decelerate motion. Movement on both sides should be fluid and symmetrical. Using a measuring tape, a floor grid and a pole or plum line enables a standardised and repeatable evaluation, which both reveals deficits and assesses the effectiveness of treatment.

Treatment

*Acute phase- Focus on decreasing pain and inflammation at the lateral knee. Rest is the first line of defence against further damage. For a low-grade injury, this may mean a few days off from training and amending external causes. Buying new shoes, avoiding downhill runs, or running the opposite direction on a track may clear up the condition quickly.With grades IV and V injury, stop all training activity during the acute period other than swimming with a pool buoy. Manage discomfort and swelling with modalities and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as directed. If obvious swelling and pain persist despite conservative management, suggest a localised corticosteroid injection.

*Sub-acute phase - When the acute pain and inflammation subsides, begin the sub-acute phase of treatment (see table 2). The goal of this phase is to improve flexibility, joint range of motion, and strength in open-chain positions. Progress the exercise program from two sets of 8-12 reps, to three sets of 15 reps. When these can be performed without pain, add difficulty to exercises with a resistance band. Progress to recovery phase activities when the athlete can execute resisted exercises without pain.

| ITB stretch (see figure 3); |

| Dynamic stretches; |

| Manual therapy, strain/counter strain, contract-relax and muscle energy techniques, to treat restrictions, trigger points and tightness; |

| Clam shell; |

| Bridge; |

| Hip extension in quadruped; |

| Fire hydrant in quadruped; |

| Hip abduction wall slides in side-lying; |

| Pelvic drop/hip hike. |

Progress exercises, adding reps and resistance with therapy band as tolerated.

Figure 3: ITB stretch

Evidence suggests that this stretch is most effective when compared to others(3). Perform the stretch three times and hold for 30 seconds each time. Keep shoulders and hips stacked vertically and avoid twisting the spine.

The hallmark of the recovery period is beginning functional closed-chain strength training (see table 3). These exercises emphasise eccentric muscle contractions and tri-planar movement, because that is how the muscles work in the unilateral stance phase of gait. Provide visual and verbal cues in a mirror while the athlete moves through the exercises.

The next step is to transition biofeedback from these exercises to treadmill running, providing visual and verbal cues for gait retraining. A study at the University of Kentucky found that such cues resulted in decreased hip adduction, internal rotation, and contralateral pelvic drop in ten runners with patellofemoral pain syndrome(5). The cues, provided over eight treatment sessions (15-30 minute treatments, four times each week, for two weeks), gradually faded in the last three sessions. The study required participants to run only during the treatment sessions for those two weeks. The changes in gait patterns also decreased vertical load rates - noteworthy since (as explained in part I of this series) increased strain rate is found in athletes who later develop ITB syndrome. A one-month follow up with the athletes showed they maintained their improved level of pain, function, and gait patterns without further treatment.

Table 3: Exercises for recovery phase of treatment

- Resistance band abduction squat, progressing to staggered squat;

- Step back lunge;

- Single leg squat;

- Modified star matrix exercises with visual and verbal feedback (see figure 4).

- Gait retraining using verbal and visual cues.

Perform two sets of 8-12 reps, progressing to three sets of 15 reps. When these can be performed without pain, add resistance or complexity as indicated.

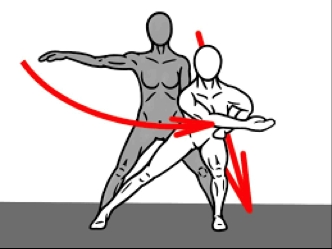

Figure 4a-4c: Modified star matrix exercises

These mimic tri-planar functional movement and the eccentric contractions necessary for unilateral stance. Verbal and visual cues ensure the hip abducts and the knee tracks properly over the foot. Perform exercises at a moderate pace, ensuring smooth and controlled weight shift.4a: Modified forward lunge with reach

Stand with one foot at 12 o’clock and the other with hip abducted toward either 3 or 9 o’clock. Reach with the hand on the abducted side across the body and touch the lateral thigh. Provide verbal and visual cues to assist this movement. Progress to reaching for lateral shin and then lateral border of the foot.

4b: Wall-touch exercise

Stand with feet about 8-12 inches away from and parallel to the wall. Extend arms out in front and reach away from the wall, pushing hips toward the wall. When hips just touch, return quickly to starting position.

4c: Side lunge and reach

Begin in standing with feet shoulder width apart and lunge to the side, reaching to that same side. Immediately return to starting position. Increase difficulty by reaching medially away from the lunge.

Return to sport

Consider return to sport when the athlete demonstrates the following:- A negative Noble compression test

- Pain-free adduction with an Ober test

- Performs exercises without pain for two weeks(3)

Recommend short, easy sprints every other day for one week, followed by longer training runs on flat terrain every other day for two to three weeks. Progress distance by no more than ten percent each week.

For cyclists, the treatment course is the same; however advise return to sport only after a thorough evaluation of bike fit. Provide biofeedback and retraining using their road bike on a trainer. Lower the seat and raise the handlebars to decrease stress on the ITB and decrease strain on the gluteal muscles. Investigate cleat position, adjusting to mirror the athlete’s normal stance posture. Utilise a shoe lift or orthotics to correct leg length or foot deformities. With a functional approach to treatment, most athletes with ITBS return to sport in roughly six weeks.

References:

- Sports Med. 2005;35(5):451-59

- Sports Med. 2005;35(5):451-459

- PM R. 2001;3:550-561

- 2006 Dec

- Br J Sports Med. 2011 Jul;45(9):691-6

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Injury Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.