You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome – A Pain in the Butt

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome affects athletes’ sporting performance, sleep, mobility, and quality of life. Samantha Nupen delves into the cluster of signs and symptoms with apparent contributing factors that aid the diagnosis of this debilitating condition.

Alpine Skiing - Saalbach, Austria - Austria’s Cornelia Huetter in action REUTERS/Lisi Niesner

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) is most common in people over the age of forty, with women outnumbering men by a ratio of up to 4:1(1). Increased adiposity and low back pain also raise the GTPS risk. It presents as pain over the lateral hip that may spread down the lateral thigh. Symptoms include difficulty lying on either side at night, standing for any length, walking, climbing (up or down) stairs, and extended periods of sitting. It is prevalent in runners, skiers, ice skaters, and dancers, where dropping into hip adduction or crossing the midline is often repetitive. In athletes, a significant increase in training load does not allow for tendon adaptation(2).

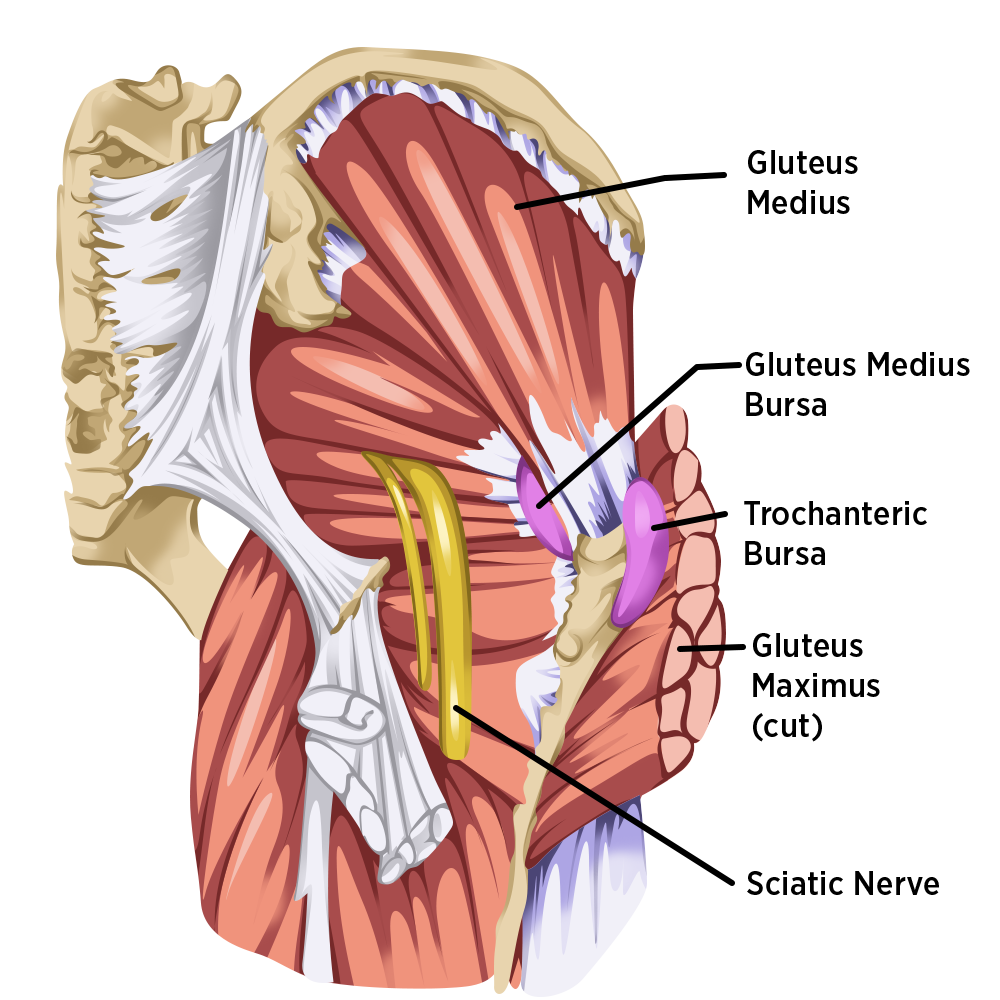

Historically, clinicians referred to lateral hip pain as trochanteric bursitis (see figure 1). However, it is now accepted that the most prevalent pathology is tendinopathy, with very few symptomatic patients showing bursal enlargement on scanning. If there is bursal involvement, it will be in the trochanteric bursa or sub-gluteus maximus bursa. Still, the predominant gluteal tendinopathy pathology is in the gluteus medius or gluteus minimus tendon.

Risk Factors for GTPS

- Age >40

- Female

- Increased Adiposity

- Low Back Pain

Risk Factors

Age

The prevalence of lateral hip pain in an older population is a strong indicator that degenerative change is a component of the pathology. Thinning, thickening, or tearing of the gluteus medius and minimus tendons is often visible on ultrasound or MRI scanning. The pathology predominantly affects the deep and anterior portions of the tendons and reduces the tendon’s tensile load-bearing capacity.

Gender

The cross-sectional insertional area of the gluteus medius tendon onto the femur is smaller in female athletes than in male athletes. Furthermore, a shorter moment arm reduces mechanical efficiency, which is further heightened in those with a smaller femoral neck-shaft angle. This creates a smaller area to dissipate tensile load.

The female pelvis, coxa vara, and larger trochanteric offset predispose gluteal tendons to greater compressive loading. Hip abductors contribute 70% to lateral pelvic stability, with iliotibial band tensioners making up 30%(1). Weakness of the abductors may result in increased contribution from the ITB. The hip abductors generate the highest forces from an adducted hip position. Women with gluteus medius muscle weakness use hip adduction more during function to provide a mechanical advantage to their abductors. Pre-tensioning the iliotibial band in adduction offers an advantage. These strategies increase the compressive load on the deep regions of the gluteal tendons. Furthermore, during menopause, females experience a drop in estrogen levels, and tendon turnover is slower.

Increased adiposity

Adipose, or fatty infiltrations in the gluteal muscles, negatively affect mean muscle volume.

Low back pain

A previous history of low back pain increases the prevalence of gluteal tendinopathy by 35%. This may be due to gluteal muscle dysfunction related to back or sacroiliac joint pain(1). Conversely, poor lateral pelvic stability increases lower back stress and results in pain. Therefore, improving gluteal tendon pain improves lower back pain.

Disturbed functional lower limb movement patterns, such as excessive hip adduction with bilateral activities (squatting and sit-to-stand) or single-leg activities (stair climbing, single-leg stance, and squat, hopping, and landing from a jump) present as excessive lateral pelvic tilt and lateral pelvic shift with hip internal rotation.

The combination of insufficient abductor strength, an increased contribution from the ITB, and excessive functional adduction is a mechanical risk factor for the gluteal tendons due to combined compressive and tensile loads.

Assessment

A comprehensive assessment includes a thorough subjective and objective evaluation. Imaging is an option in cases where the subjective and objective assessment leave doubt in the clinician’s mind. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound imaging are reasonable at identifying gluteal tendinopathy but not at identifying a specific pathoanatomical diagnosis. Therefore, imaging in isolation should not guide the treatment(3,4).

The objective assessment includes the back, pelvis, and hip to identify biomechanical contributors and compensations or rule out any severe pathology that refers to pain in the lateral hip region. Palpation will reveal the site of pain over the superior aspect of the greater trochanter(4). Straight-forward resisted hip abduction reproducing pain is a powerful indicator of GTPS(4).

Clinicians can use special tests, such as Lequesne’s version of single-leg stance for 30 seconds or the onset of pain over the greater trochanter. This test has a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 97,3%(5). Another special test is the resisted lateral rotation de-rotation test in 90o of hip flexion, which has a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 97,3%(6). Functional testing should include squats, single-leg squats, stairs (both up and down), gait, and gait uphill, and clinicians should observe for biomechanical irregularities (such as Trendenlenburg gait) and tissue capacity (e.g., number of squats or walking distance until the onset of pain).

Lequesne’s Single-leg Stance Test

- Sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 97,3%(5).

- Control for balance by allowing light fingertip support.

- Do not dictate pelvic position; only maintain the trunk vertically.

- Maintaining the trunk upright necessitates hip abduction, which results in tendon compression under active tensile load and may reproduce pain.

- The ability to control pelvic position is not measured, but noting the quality of control will help guide treatment.

Management

Avoiding Compression

Reducing compression, especially for insertional tendinopathies, is essential. Athletes should avoid hip adduction positions such as:

• standing “hanging on one hip,”

• standing or sitting with legs crossed, or

• knees together, or

• sitting at a slight angle for long road trips.

Side-lying compresses gluteal tendons on both sides, one side against the bed and the other due to the hip falling into adduction. Lying supine with a pillow under the knees to offload the anterolateral hips and lumbar spine, or if side-lying is impossible to avoid, using an eggshell mattress with a pillow between the knees will unload the tendons. The alternative is lying a quarter turn from prone with the body weight resting on the anterolateral thigh and the uppermost hip in relative abduction.

Clinicians must advise athletes to avoid hip stretches in flexion or extension due to the combined tensile and compressive forces generated in the gluteal tendons. Soft tissue release techniques away from the tendon are more useful than stretching. Correcting movement patterns and controlling high tensile loads with graded exercise volume is critical.

Load Management

Athletes rarely have to cease sports participation completely when recovering from GTPS. They can modify their load and minimize exposure to exercises that may exacerbate their symptoms, such as avoiding long-distance, tempo and hill running, or plyometric drills. They can use cross-training to maintain cardiovascular conditioning, such as water-based exercise and cycling. Athletes should stay active but monitor symptoms closely and, if possible, avoid complete rest as it may result in a recurrence or prolonged recovery - tendons must be loaded.

Table 1: Exercise Intervention Recovery Timeline(1)

| Time Frame | Percentage of Participants that Improved |

| Four weeks | 7% |

| Four months | 40% |

| 15 months | 80% |

Isometric exercise

As with other tendons, sustained isometric contractions have analgesic effects.

Isometric contractions activate segmental and extra-segmental descending pain inhibitory pathways, and sustained low-intensity contractions (25% MVC) are most effective.

Five 45-second isometric holds held at 25% MVC provides almost complete relief for up to 45 minutes (see figure 2). Once the patient response has been assessed, load in a non-pain-provocative manner, progressing to higher loads in at least some hip abduction to avoid compression.

The athlete stands, holding lightly onto the back of a chair. They transfer their weight onto the painful leg. Lift the opposite foot about an inch off the floor, and keep the knee straight. They will feel their pelvis shift and gluteus medius contract. They hold this contraction for 45 seconds, place the foot back on the floor, and rest for two minutes. They repeat this five times. The sequence will take 13 minutes and 45 seconds if they complete the last two-minute rest. The timings are essential. A bit of discomfort is normal, which should ease as they build capacity and repeat the exercise

Exercise Therapy

Restorative loading through an early and gradually progressive tensile loading program in positions of minimal hip adduction reduces pain and improves the tendon’s tensile load-bearing capacity. Clinicians must prescribe strengthening exercises that re-educate movement and postures under graduating difficulty levels appropriate for the individual.

Low-velocity, high-tensile load exercises

Clinicians should incorporate low-velocity, high-tensile load exercises as soon as possible to achieve muscle hypertrophy and improve the tendons’ load-bearing capability (see table 2)(7). These exercises also have beneficial effects on tendon structure. Weight-bearing exercise promotes higher levels of gluteus medius activation than non-weight-bearing exercise. Furthermore, moving into inner-range abduction minimizes the compressive load, and ITB tensioners are mechanically disadvantaged.

Table 2: The ten exercises that elicit the highest glute medius maximal voluntary isometric contraction(7)

| Exercise | MVIC (%) |

| Side-bridge to neutral spine position | 74 |

| Single-leg squat | 64 |

| Single-leg deadlift | 58 |

| Pelvic drop | 57 |

| Side-lying hip abduction | 56 |

| Wall squat | 52 |

| Transverse lunge | 48 |

| Single-leg bridge | 47 |

| Forward step-up | 44 |

| Four-point kneel with opposite arm/leg lift | 42 |

Exercises should be prescribed with adequate rest between sessions to allow physiological adaptations to occur and minimize accumulative fatigue. Three times per week, not on consecutive days, allow for sufficient recovery and adaptation. Athletes should start with moderate effort and low repetitions and assess tendon response. A reduction in night pain is a good indicator of exercise response.

Movement Retraining

During exercise, pelvic control training and femoral alignment correction are the first steps in re-education of movement(8). Using cues during exercise falls into the cognitive stages of learning as it increases awareness and proprioception(8). Then, clinicians must progress the program to the associative stages of learning, where task difficulty increases. Associative learning requires athletes to improve their biomechanics during various tasks using visual feedback and verbal cues, such as running with their knees apart and kneecaps pointing forward.

Clinicians should focus on reducing hip adduction during running and task-specific movement retraining. The most effective way to improve running biomechanics is verbal cueing and deliberate practice(8). Any running gait changes must be made gradually, as adaptation is necessary. Rapid changes without consideration of training intensity, distance, and speed may increase the risk of injury. As athletes improve, clinicians can increase the load, speed, and exercise complexity (sport-specific activities).

Manual therapy

Manual Therapy includes joint, neural, and soft tissue mobilization of the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joints, and the hip. When using myofascial release techniques, clinicians should target the lateral line from latissimus dorsi to tensor fascia latae, the iliotibial band, and the distal to the knee.

Conclusion

Physiotherapists can use load management, avoiding excessive compressive and tensile forces, progressive rehabilitation, and manual therapy to help athletes battling greater trochanteric pain syndrome. This multifaceted injury requires a well-planned clinical program to ensure optimal recovery. Furthermore, clinicians must manage athletes’ expectations regarding return to full health.

References

1. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2004, 70: 423-428

2. prpphysio.com/gluteal-tendinopathy-its-a-real-pain-in-the-ass/#ib-toc-anchor-0

3. JOSPT 2024, 54;1: 3-6

4. JOSPT 2024, 54;1: 26-50

5. Arthritis Rheum 2008, 15;59(2):241-6

6. JOSPT 2015, 45;11: 910-922

7. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 28:4, 257-268

8. J Clin Med. 2022 Nov; 11(21): 6497

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.