Chronic heel pain: a case of Baxter’s nerve injury?

Pain in and around the heel is a common complaint in running-based athletes. In most cases, injury to the plantar fascia is the most common cause. However, it has been estimated in about 20% of cases of medial heel pain, a neuropathy of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (inferior calcaneal nerve - commonly known as ‘Baxter’s nerve’) may masquerade as a plantar fascia injury(1-6). Injury to Baxter’s nerve is a frequently overlooked cause of medial heel pain.

Anatomy

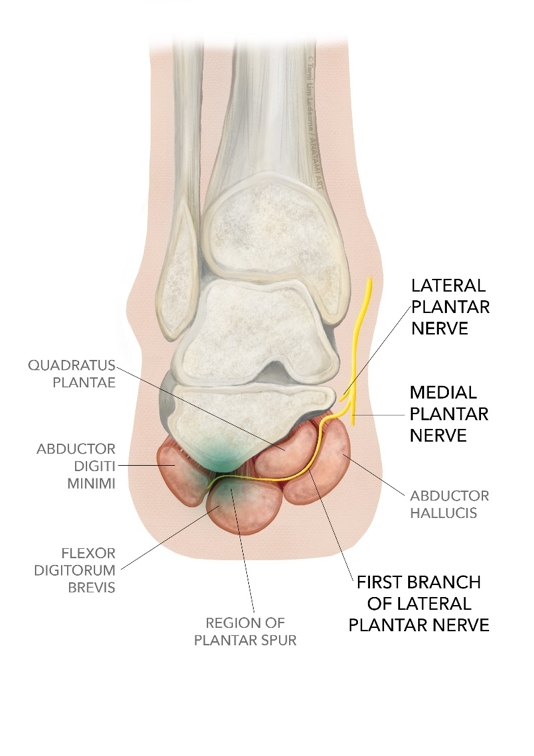

Baxter’s nerve originates from either the lateral plantar nerve, near the bifurcation of the tibial nerve, or from the tibial nerve prior to its bifurcation (see figure 1). In most instances (82.1% of cases), the nerve originates as first branch of the lateral plantar nerve, which divides itself at the level of the medial malleolus. However, some anatomical variants have been noted(7):- In 11.7% of cases, this nerve may present as a direct branch from the posterior tibial nerve.

- It may originate from a common branch, with the posterior branch to the lateral plantar nerve and with the medial calcaneal branch (4.1%).

- It may originate from a branch in common with the posterior branch to the plantar square (2.1%).

As the nerve courses vertically downward, it is situated superficial to the fascia at the superior border of the abductor digiti minimi muscle (ADMM). It has been noted here that the fascia is laterally thicker due to the connection between the medial intermuscular septum - and the interfascicular ligament, which reinforces the lateral fascia.

The nerve then continues distally between the medial edge of the quadrutus plantae muscle and the lateral abductor fascia. At the lower border of the abductor hallucis muscle, it turns and moves laterally passing anterior to the medial calcaneal tuberosity and between the quadrutus plantae and the underlying flexor brevis - until it finally reaches the abductor digiti minimi(8-10). The nerve has sensory fibres that innervate the calcaneal periosteum and long plantar ligament, and motor fibres for the quadrutus plantae, flexor digitorum brevis and ADMM(1,9).

Figure 1: Anatomy of the nerves in the foot

Pathogenesis

Initially described by Baxter and Thigpen in 1984(11), entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve is a hard-to-diagnose condition that may mimic plantar fasciitis, and one that often co-exists with plantar fasciitis. It is in fact one of the many causes of medial heel pain. Differential diagnoses of heel pain include(12):- Plantar fasciitis

- Entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve

- Fat pad disorders

- Calcaneal body stress fractures

- Fatigue fractures of the medial calcaneal tuberosity

- Plantar aponeurosis rupture

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome

- Sciatica

- Painful piezogenic heel papules

- Glomus tumor of the heel pad

There are a number of areas where the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve can become entrapped(8-11). These include:

- Between the deep fascia of the abductor hallucis and the medial caudal margin of the medial head of the quadrutus plantae (see figure 2 below).

- Where the nerve passes through the deep fascia of the abductor hallucis.

- In the region of a co-exiting plantar spur (figure 2 below).

- Where the nerve passes anterior to the medial calcaneal tuberosity.

- Between the flexor digitorum brevis muscle and the calcaneus(12, 13).

Figure 2: Areas of ‘Baxter’s nerve’ compression

It has also been noted that the nerve may be entrapped following surgical procedures such as plantar fasciotomy, because the fascia migrates distally after these procedures. The resultant scar tissue may entrap the nerve. The pathomechanics that may predispose an athlete to this problem include:

- Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, which results in excessive midfoot pronation and rearfoot valgus.

- Co-existing achilles tendinopathy, which may limit dorsiflexion and result in a compensatory overpronation.

- Mechanical compression of the nerve due to plantar fasciitis and/or plantar calcaneal enthesophytes(8).

Signs and symptoms

Compression of Baxter’s nerve presents as chronic medial plantar heel pain, which is frequently similar in location to that of plantar fasciitis. Often, it may accompany chronic plantar fasciitis(8). This is due to focal oedema from the plantar fascia, which can lead to entrapment of the nerve. However, there are a few signs and symptoms of Baxter’s nerve entrapment that may help the clinician differentiate this problem from plantar fasciitis. These include(13-15):- Pain is usually more proximal and medial, usually just distal to the medial calcaneal tuberosity.

- Absence of early morning pain, instead tending to get worse as the day goes on, or pain appearing after prolonged activity.

- A radiating pain may be present when the nerve is palpated.

- Pain is exacerbated by passive eversion and abduction of the foot.

- There is maximal tenderness at the medial border of the heel where the entrapment occurs - usually around the origin and deep to the abductor hallucis. This may create radiating and/or burning pain laterally across the plantar foot.

- There is a positive Phalen’s test (invert and plantarflex the foot passively). This compresses the nerve due to narrowing of the porta pedis.

- There may be weak abduction of the fifth toe. This is due to the ADMM.

- There may be a positive Tinel’s sign. Paresthesias may be reproduced with tapping over the nerve beneath the abductor hallucis muscle.

- In chronic cases, patients may have diminished sensation in the lateral plantar foot.

- A diagnostic block at the site of the nerve may help confirm the diagnosis(16).

A potential physical test that the clinician can use is an adaptation of the tibial nerve test as described by Shacklock(17). As the lateral plantar nerve branches off the tibial nerve, the tibial nerve test may be used to identify a neurodynamic interface issue with ‘Baxter’s nerve’. This test is performed in the following way:

- The patient lies supine.

- The clinician holds the affected foot and pushes the foot into ankle dorsiflexion and notes symptoms.

- The clinician should then lift the leg into hip flexion, with the knee in extension and the foot maintained into dorsiflexion. Note any symptoms particularly medial heel pain.

- To differentiate whether the issue is a nerve problem, a tendon issue or something else, a sensitiser is required that will change the nerve tension. This is done by dropping the hip slowly out of flexion and noting if the symptoms change. If the medial heel pain improves with less hip flexion, then the tibial nerve and its branches are implicated.

Imaging

Plain film X-rays can help to exclude bone pathology such as calcaneal spurs. However, MRI is the gold standard investigation for ‘Baxter’s nerve’ entrapment. MRI can determine the presence or absence of inflammation around the proximal fascia, as well as thickening of the fascia.Atrophy, increased water signal and fatty infiltration of the ADMM may indicate chronic nerve entrapment leading to atrophy of this muscle(5,18,19). Such findings are clearly depicted at T1-weighted images without fat suppression(20-22). Typically, atrophy and fat infiltration occur homogeneously in the muscle belly.

To support the clinical suspicion that ‘Baxter’s nerve’ compression often accompanies plantar fasciitis, Chundru et al showed a significant association between atrophy of the ADMM with age, plantar calcaneal spur formation, and plantar fasciitis(23). The pathological state of the plantar fascia may potentially compress the nerve as it passes anterior to the medial calcaneal tuberosity.

Treatment

Treatment of a compressed Baxter’s nerve resembles initial treatment of a plantar fasciitis. Techniques that may initially be used include(12,24,25):- Taping and/or orthotics to control overpronation.

- Stretching of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles.

- Soft tissue therapy to the plantar fascia and foot intrinsic.

- No steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDS).

- Strengthening exercises for the foot intrinsics.

Patients with an entrapped Baxter’s nerve often have a relatively slow and poor response to conservative treatment. Therefore, if symptoms persist for longer than six months, the next course of action is a steroid/local anaesthetic injection in and around the nerve. This is diagnostic as well as therapeutic. If there is a relief of symptoms with the injection, this points to a nerve entrapment being the source of symptoms. If not, then plantar fascia injury will be the most likely scenario. If a local steroid injection fails, a surgical intervention may be required. This may consist of decompression of the nerve by endoscopic approach, radiofrequency ablation techniques or open surgery(12,25-27).

The recommended procedure is complete neurolysis by first releasing the proximal deep fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle. Further surgical release is accomplished by following the nerve distally, and releasing it from any entrapment caused by the medial plantar fascia or the flexor digitorum brevis at their insertion to the calcaneus. If there is an impinging bone spur in this area, a small portion may be removed if necessary, but removing the entire spur is not recommended because this action may lead to adverse outcomes(11,28).

Summary

Chronic medial heel pain is a common complaint in running-based athletes. In most cases, the source of pain is most likely plantar fasciitis. However, another potential source of pain is the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve, also known as Baxter’s nerve. Often, Baxter’s nerve neuropathy may co-exist with plantar fasciitis.The major biomechanical factors relevant in this condition are similar to plantar fasciitis and these include rear foot valgus, over pronation of the midfoot and a lack of dorsiflexion. The typical signs and symptoms may be similar to plantar fasciitis. However, a few distinct signs and symptoms may help the clinician differentiate this condition from plantar fasciitis. Treatment may initially involve conservative management; however, in recalcitrant problems, surgery may be required.

References

- Radiographics 2003; 23: 613–623

- Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:208–11

- J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1981;71:119–24

- Baxter DE. Release of the nerve to the abductor digiti minimi. In: Kitaoka HB, ed. Master techniques in orthopaedic surgery of the foot and ankle. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002: 359

- AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189: W123–7

- Arch Orthop Trauma Surgery. 2006, 126; 6-14

- Radiol Anat. 2002;24:18–22

- Podiatry Today 2004; 17: 52–58

- Acta Morphol Neerl Scand. 1986. 24: 269-279

- Surg Radiol Anat 1999; 21: 169–173

- Foot Ankle. 1984. 5; 16-25

- Clin Orthop and Related Research. 1992; 279. 229-236

- Foot Ankle Int 1994;15(10): 531-535

- 2008; 24. 1284-1288.

- Foot Ankle. Mar-Apr 1993;14(3):129-135

- Clinical Journal of Sports Med. 2001; 11. 111-114

- Shacklock (2005) Clinical Neurodynamics. A new system of musculoskeletal treatment. Elsevier. Sydney

- Radiology 2001; 221(P): 522

- Man Ther. 2008;13:103–11

- 2011;31:319–32

- 1993;187: 213–8

- Radiol Bras. 2015 Nov/Dec; 48(6):368–372

- Skeletal Radiol. 2008; 37:505–510

- Arch Orthop Trauma Surgery. 2007; 127. 859-861

- J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(3 Suppl):S1–19

- Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2010;20:563–7

- Foot Ankle Spec. 2010; 3:338–46

- Acta Orthop Belg 2008;74(4):483-488

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Injury Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.