You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Baxter's Nerve Entrapment: When Feet Throw a Tantrum

In this article, James Nowosielski reviews the structures involved in Baxter’s nerve entrapment and unpacks how clinicians can help their athletes recover.

Rajiv Gandhi International Cricket Stadium, Hyderabad, India - India’s Rohit Sharma in action REUTERS/Francis Mascarenhas

When it comes to foot pain, the heel is the most common complaint, and typically, it is associated with the plantar fascia(1). Plantar fasciitis is challenging to treat, and rehabilitation can frustrate the clinician and the athlete. But not all heel pain is caused by this, and among the many other potential foot-related maladies, one that often goes unnoticed is Baxter’s nerve entrapment.

Clinicians often overlook Baxter’s nerve entrapment as a source of heel pain. Up to 20% of chronic heel pain can be attributed to it(2). Before diving into more in-depth anatomy, Baxter’s nerve entrapment occurs when the inferior calcaneal nerve gets stuck in a tight spot, usually around the heel area of the foot.

While Baxter’s nerve entrapment doesn’t discriminate, it targets specific groups more than others. Athletes, especially those participating in sports that involve repetitive heel strikes, are often at risk. Runners, basketball players, and dancers beware! Additionally, people with flat feet or a tendency to overpronate may be at greater risk. The subjective assessment is critical to uncover the past medical history and current physical activity load. Furthermore, anatomical variations, such as a cyst or bone spur, or wearing tight-fitting shoes also increase the risk of developing an entrapment. There is also speculation that chronic plantar fasciitis irritates the inferior calcaneal nerve. Despite the high prevalence of foot pain in athletes and non-athletes, foot care is way behind heart, eye, teeth, skin, and nutritional care(3).

Anatomy

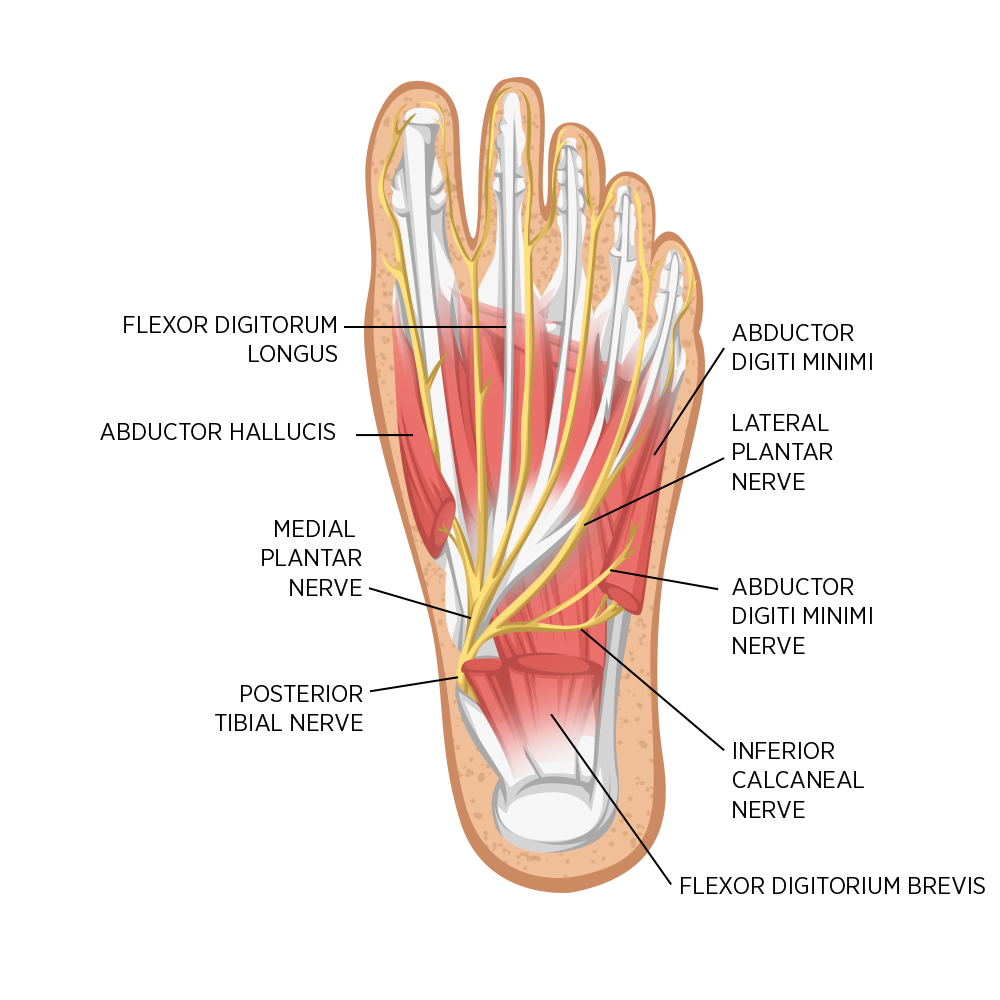

The tibial nerve derives from the sciatic nerve and is a major peripheral nerve of the lower limb. It innervates the leg and foot in many ways, including sensation and motor function. It then splits into various branches; the medial calcaneal branch arises within the tarsal tunnel to innervate the skin over the heel. The medial plantar nerve innervates the plantar surface of the medial three-and-a-half digits of the foot (see figure 1).

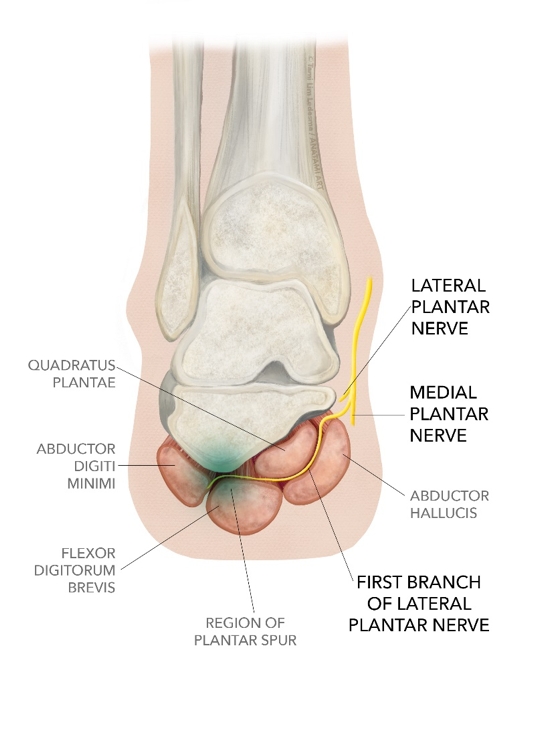

The lateral plantar nerve, where Baxter’s nerve stems from, innervates the plantar surface of the lateral one-and-a-half digits as well as the motor fibers to the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digitorum brevis, and quadratus plantae. The inferior calcaneal nerve, or Baxter’s nerve, is the first branch of this lateral plantar nerve.

The inferior calcaneal nerve then hooks underneath the calcaneus through the superficial fascia at the superior border of the abductor digiti minimi. The nerve travels along the medial edge of the quadratus plantae. As it reaches the border of the abductor hallucis, it turns and passes anteriorly to the medial calcaneal tuberosity until it reaches its distal target of the abductor digiti minimi(2). It also functions as a sensory nerve to the fat pad under the heel. Therefore, any injury or irritations result in severe heel discomfort.

Clinical Presentation

Baxter’s nerve is vulnerable to entrapment due to the course it takes (see figure 2). There are two areas where this is most likely to happen. The first is where the nerve turns laterally between the medial edge of the quadratus plantae and the thick lateral fascia of the abductor hallucis. If this becomes particularly tight, it can contact or compress the nerve, causing pain and numbness. The second point is where the nerve moves anteriorly past the calcaneal tuberosity. If the space the nerve occupies narrows due to a bone spur, muscle hypertrophy, or overpronation of the rearfoot/midfoot complex, impingement can occur.

When clinicians start their objective assessment, they look for an overpronated foot. This is a big part of the jigsaw when putting pieces together with the clues picked up during the subjective assessment. Common symptoms and assessment tests:

1. Pain is the most common symptom and is a nagging pain right beneath the heel. Athletes often describe it as a sharp, burning, or aching sensation. This is most likely to flare up after an activity involving repeated heel strikes, such as walking, running, or other sports. Tenderness often occurs above the abductor hallucis origin, which can induce laterally radiating discomfort and paraesthesia. It is also common for athletes to report sharp radiating pain at night after exercise(4).

2. Numbness can occur if the nerve becomes compressed rather than just irritated. As a result, athletes may experience tingling or numbness in the heel area.

3. Swelling is another common symptom of nerve entrapment due to the irritation. This can range from mild to severe.

4. Atrophy of the innervated muscles. It may be difficult for clinicians to identify muscle wasting, particularly of the abductor digiti minimi muscle. However, they should maintain high suspicion during the objective assessment(5).

5. Tinel sign is a common neurological test to assess nerve entrapment. When assessing the heel, clinicians can use it to rule out tarsal tunnel syndrome, where the anterior tibial branch of the deep peroneal nerve is also affected(4). For clarity, this is the same nerve as Baxter’s nerve entrapment; however, it is more proximal.

6. Modified Phalen’s test attempts to replicate the athlete’s heel symptoms when the clinician passively inverts and plantar flexes the foot(5).

7. The Windlass test helps to rule out plantar fasciitis.

All of these tests and symptoms, together with an excellent subjective history, will direct clinicians toward a diagnosis, but in some cases, imaging such as ultrasound or MRI may be necessary to rule out sinister pathologies or identify the cause of nerve entrapment.

Differential Diagnosis

As with all conditions, clinicians must consider alternative pathologies. A differential diagnosis creates scope for clinical reasoning when the primary treatment plan is unsuccessful. The heel is a complex anatomical region and clinicians need sound background knowledge to identify alternative causes of pain.

Heel Pain Differential Diagnoses

• Plantar fasciitis

• Tarsal tunnel syndrome

• Seronegative arthritis-induced inflammation

• Medial calcaneal neuritis

• Heel spurs

• Trauma

• Fat pad atrophy

• Calcaneal stress fractures

• Periosteal inflammation

Management

Once clinicians think they have identified a nerve entrapment as the primary cause of pain and dysfunction, they can develop management strategies to aid athlete recovery. Many options are available, and they must identify which is best based on their assessment. Once they identify the primary cause, they must target that as the first treatment option.

There is no single correct answer, as research shows no optimal treatment strategy. Treatment options range from rest and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories to open distal tarsal tunnel release(6). As a first treatment line, clinicians typically recommend rest, but, as with so many injuries, this is rarely the sole answer. Other passive modalities include massage, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and shockwave therapy. However, despite these modalities resulting in short-term relief, failure to address the underlying cause will result in the symptoms returning.

For example, if clinicians identify over-pronation as the primary cause. They must assess the entire kinetic chain to determine why the foot is taking strain. In overuse injuries, the site of pain may be the region that is taking strain due to irregular force distribution or mechanics in other areas along the kinetic chain. In over-pronation, clinicians must assess knee, hip, and lumbopelvic strength and mechanics. Addressing these deficits through a comprehensive rehabilitation program is the best chance for long-term success. As a shorter-term solution, clinicians may consider orthotics to help offload the heel and distribute weight more evenly around the foot during rehabilitation.

Furthermore, clinicians must ask questions about training volume and intensity. Tissue capacity is essential for lower limb sports; if an athlete’s training schedule is more demanding than their capacity, they are at risk for injury. They must maintain a stress vs. recovery balance. As clinicians suggest a period of active recovery, they can advocate for athletes to improve their capacity through strength training, i.e., replacing running time with strength training sessions. They must work closely with the athlete to create a personalized treatment plan that suits their needs and lifestyle.

Conclusion

Baxter’s nerve entrapment might be a sneaky little troublemaker, but with the proper guidance, clinicians can help their athletes send this foot gremlin packing. Plantar heel pain is notoriously difficult to treat, and clinicians may miss Baxter’s nerve entrapment. So, if the primary treatment plan is not working, they might want to consider this!

References

- A&A Prac. 2020 Nov; 14(13):e01339

- Pod Today. 2004 Nov; 17(11)

- APMA. 2014 Jan

- StatPearls Pub. 2023 Jan

- Arch Clin Exp Orthop. 2023 Feb ;7:003-004

- Op Tech in Sports Med. 2021 Sep ;29(3):150854

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.