You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The control-chaos continuum: A thinking tool for rehabilitation professionals

Africa Cup of Nations - Group C - Morocco v Comoros - Stade Ahmadou Ahidjo, Yaounde, Cameroon - Comoros' El Fardou Ben Nabouhane in action with Morocco's Sofyan Amrabat REUTERS/Mohamed Abd El Ghany

Return to performance

In 2016, leading sports injury rehabilitation experts drafted a consensus statement to define the three critical return to sport (RTS) stages following injury(1). These exist on a continuum and are designated (1) return to participation, (2) return to sport, and (3) return to performance (see figure 1).Figure 1: The return to sport continuum(1)

- Return to participation - The athlete participates in rehabilitation, training (modified or unrestricted), or sport, but at a level lower than their RTS goal.

- Return to sport - The athlete returns to their defined sport but is not performing at their desired performance level.

- Return to performance - Athletes gradually return to their defined sport and perform at or above their pre-injury level.

The RTS continuum highlights that the role of sport rehabilitation professionals extends well beyond returning athletes to participation. The job doesn't stop when the athlete is pain-free and functionally capable. Practitioners need to support athletes in going as far down the RTS continuum as they wish. Some individuals will be satisfied with returning to sport; however, others won't be satisfied until they reach or beat their previous best. In either case, the practitioner's role is to support this journey fully.

A major frustration for any athlete is re-injury following a period of rehabilitation. Sadly, this happens frequently, with one in five athletes that undergo ACL reconstruction experiencing re-injury when they RTS(2). Outcomes are worse for hamstring strains, where re-injury occurs in one out of every three athletes(3). As a result of figures like these, a previous injury is one of the main risk factors for sports injury(4). The sports medicine fraternity needs to reflect on the high re-injury rates and determine if re-injury is inevitable or a reflection of the mismatch between inadequate rehabilitation processes that fail to prepare athletes for the demands of their sport. Taking athletes further along the RTS continuum improves their chances of staying injury-free, performing well, and increasing their enjoyment.

What is performance?

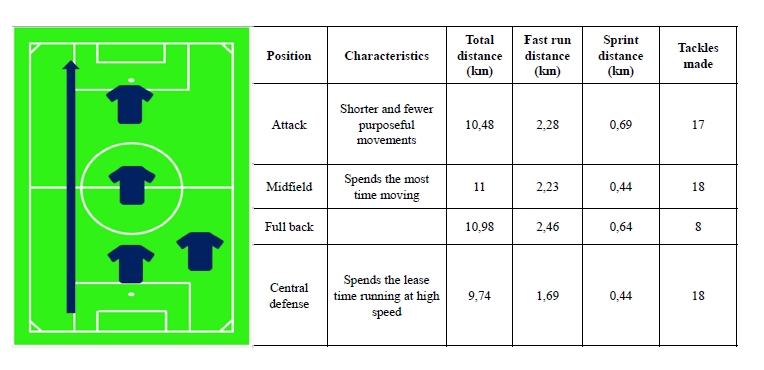

The first challenge in adopting the return to performance approach is understanding performance. This is an area where searching for and interpreting research is invaluable. Sports scientists regularly assess and document the physical demands of various sports to inform training and rehabilitation practices. For example, researchers at the Institute of Exercise and Sport Sciences at the University of Copenhagen summarised the physical demands of matches and training for professional footballers(5). This research reveals that elite players may run up to 13 km in a game, including 2.4 km at high intensity and 650m sprinting. In addition, players perform up to 250 brief, intense actions such as accelerating, decelerating, changing direction, tackling, and jumping within a game.Basketball is similar, as researchers in Spain reveal that, on average, a professional basketball player runs 72m and performs three hard accelerations and decelerations per minute of match play(6). This information is highly informative regarding the sports demands and physical capacity required by athletes returning to performance. However, it is essential to remember that these demands will vary according to sex, age, and level of competition. Therefore, clinicians should use cohort norms that best represent their athletes and sport-specific demands.

Figure 2: Physical demands for professional football participation by position(7).

Losing control

The sports injury rehabilitation environment is a safe, structured, and controlled space for athletes to redevelop tissue capacity and confidence. There are generally no opponents, and clinicians typically create an environment where athletes return to participation by progressively demonstrating various physical skills and capabilities such as straight-line running, progressive accelerations, deceleration, and plyometrics. Once athletes can demonstrate a certain level of competency, a clinician may initiate the return to participation. However, although these activities are necessary steps on the rehabilitation pathway, they are different from playing or performing on a sports field.The critical difference is that the sports field is unsafe, unstructured, and unpredictable. In rehabilitation settings, the movement challenges allow athletes to plan before executing. However, the sports performance environment offers athletes few opportunities to plan and execute. Instead, athletes have to react in response to an opponent or teammate. Sport movement patterns are a collection of hundreds of mini duels between opponents where both are continually trying to gain an advantage over the other. For example, there is a significant difference between a jump landing in rehabilitation and attempting to land after an aerial duel with an opponent.

Clinicians and athletes need to realize that the sports environment is chaotic and does not mimic safe rehabilitation settings. This will lead clinicians to understand that to progress athletes through the RTS continuum appropriately, they need to progressively expose them to the chaos of real-life sports environments. If clinicians fail to do so, they can only hope for the best when athletes RTS. Fortunately, researchers working in England's professional football leagues have mapped out an approach for safe return to performance –' Control -Chaos Continuum' (CCC)(8,9).

The control-chaos continuum

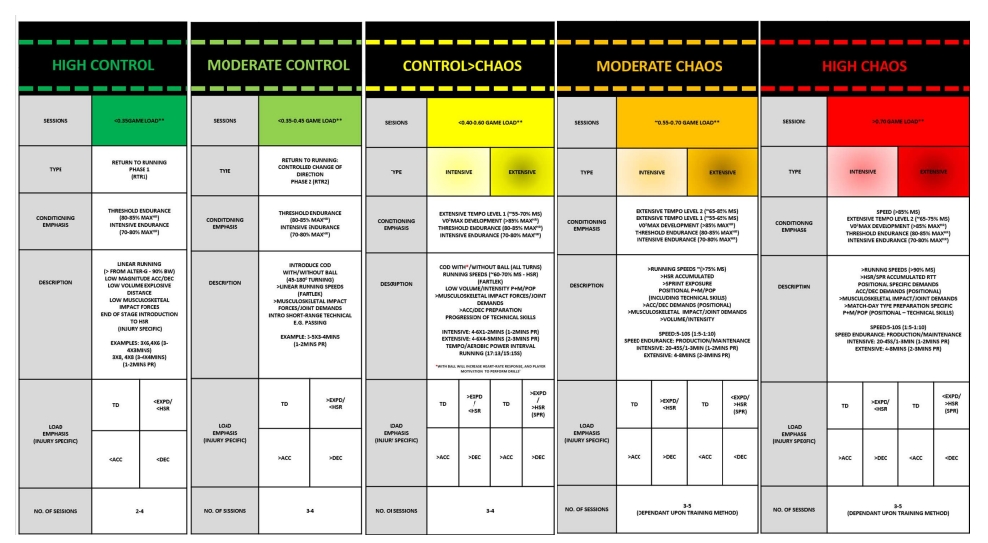

The CCC is an approach to planning and periodizing sports injury rehabilitation that reintroduces progressively more game-like activities at each rehabilitation stage. This approach ensures that the athlete is adequately prepared for their sport's unpredictable and chaotic environment (see figure 3). The CCC progresses through five stages based on the attainment of objective neuromuscular strength and power diagnostics(10).High Control

In this phase, athletes return to running with high control over speeds and volumes. The aim is to gradually redevelop the aerobic system while limiting musculoskeletal forces and developing player confidence. The critical components of the high control phase include:

- Limit exposure to high speed running (<60% max sprint speed)

- Minimize high-intensity accelerations and decelerations

- Minimize sport-specific tasks (with a ball)

Moderate Control

In this phase, athletes progressively increase the load by adjusting speed and introducing a change of direction tasks. Clinicians introduce low load technical skill tasks such as passing and dribbling. The critical components of the moderate control phase include:

- Increase linear running speed to 70% of maximum

- Introduce change of direction activities with and without the ball

Figure 3: Return to sport framework - the control-chaos continuum(8).

Control is a high level of structure on behavior/actions/movement, whereas chaos is the unpredictable behavior/actions/movement, as to appear random/reactive. Green represents high control (low intensity) moving towards high chaos (high intensity).

Control > Chaos

In this phase, clinicians introduce and progress perceptual and reactive elements to the rehabilitation process. The addition of coaching staff or teammates to drills increases the neurocognitive and perceptual demands. In addition, the training structure should now resemble the weekly periodization scheme of the athletes' team. This allows athletes to develop different physical qualities on separate days and ensures that the athlete is ready to return to team training. The critical components of the control > chaos phase include:

- Running at higher speeds (65-80% of maximal speed)

- Train in smaller areas to stimulate acceleration, deceleration, and change of direction skill

- Introduce reactive passing and movement that aims to replicate position-specific movement patterns

Moderate Chaos

Once athletes reach the moderate chaos phase, clinicians introduce high-speed running volume and change of direction challenges by presenting these within the positional pattern of play activities. Unanticipated movements frequently occur due to variability in the passing and movement of other players. The intensity of these activities should be similar to match demands, and the key components include:

- High speed running >75% maximum speed with subtle changes of direction

- Introduce position-specific running patterns

- Position-specific pass and move drills

High Chaos

The final phase of the CCC is high chaos. When reaching this stage of the rehabilitation process, training should now be specific. The training structure should precisely replicate the team's training program to allow for a seamless transition. Training activities should now challenge the athlete's ability to perform under fatigue or during 'worst-case scenario' high-intensity phases of play. Practitioners increase the number of players involved in drills and introduce a competitive element that puts significant pressure on recovering athletes. The key components of the high chaos phase include:

- Practice high-intensity skill maneuvers like shooting, crossing, and tackling

- High volumes of technical skill executions within the position-specific speed and endurance challenges.

Summary

The sports injury rehabilitation process should aim to return players to performance. Unfortunately, too many rehabilitation programs stop at the point of the athlete simply being pain-free but unprepared for the demands of their sport – this is a significant factor in the high rates of re-injury in sport. It is important to understand the physical, technical, and tactical demands players are exposed to and replicate these in training to return a player to performance. The Control-Chaos Continuum is a structured return to performance program that progressively increases physical, technical, and tactical training demands. The CCC is a blueprint for a return to performance in multiple sports.References

- Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;50(14):853-64.

- Sports Health. Nov/Dec 2020;12(6):587-597.

- J Sport Health Sci. 2017 Sep;6(3):262-270

- Int J Sports Phys Ther.2014 Oct; 9(5): 583–595

- J Sports Sci. 2006 Jul;24(7):665-74.

- J Sports Sci Med.2020 Jun; 19(2): 256–263.

- J of Sports Sci21(7):519-28

- Br J Sports Med. 2019 Sep;53(18):1132-1136.

- Phys Ther Sport. 2022 Jan;53:67-74

- Phys Ther Sport. 2021 Jul;50:22-35

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.